Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners, as revealed by English Heritage properties.

FOCAL POINT

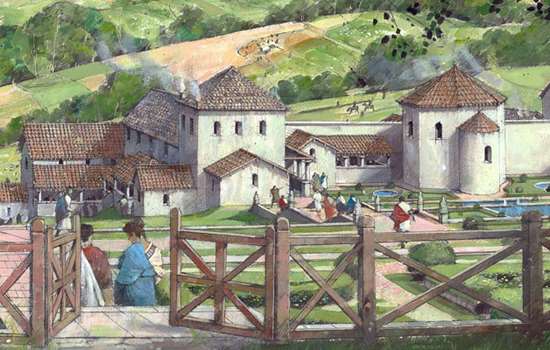

One of the most iconic types of rural site known from the Roman period, the villa rustica was normally the centre of a farming estate.

The villa was more than a comfortable house, often being the focus for a community that might include several generations or branches of a family, their servants, estate workers and probably slaves.

EXTENSIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS

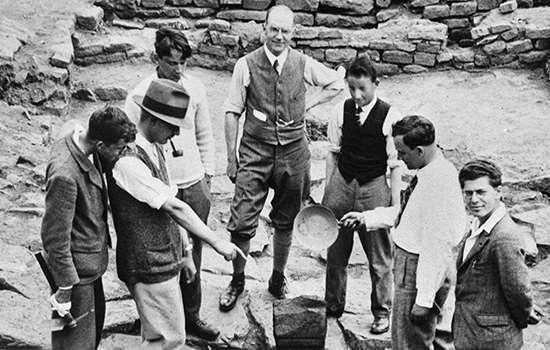

Many of the greatest villa houses known from Roman England, such as North Leigh, Oxfordshire, developed over decades or even centuries, reaching their peak in the 4th century. Others such as Great Witcombe, Gloucestershire, were probably only begun in the 3rd or 4th centuries, but were built on a relatively grand scale from the start.

At some sites the villa began as a small range, either aisled (like a church) or, most commonly, with extra rooms extending forward in wings at either end, linked by a corridor or veranda. Such ‘winged-corridor’ houses were often gradually extended, or replaced by grander and more elaborate structures – often a series of ranges or buildings around a courtyard, as at North Leigh.

These villas bore many signs of ostentatious luxury. They would have at least one suite of baths, and might be decorated with painted plaster (as at Lullingstone in Kent) and the floors covered with expensive mosaics – fine examples of which survive at North Leigh, Lullingstone and the Roman town of Aldborough, North Yorkshire.

Villa houses could have one or two storeys, and some would also have had brightly painted external walls, like their Mediterranean counterparts.

They would also incorporate housing for workers as well as farm buildings, as are known at North Leigh and Beadlam (North Yorkshire). Most buildings apart from the villa house itself would have been single-storey, and would have had pitched roofs, covered with ceramic or stone tiles, wooden shingles or thatch.

SEAT OF POWER

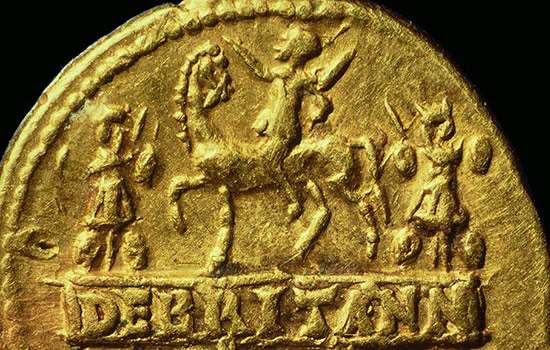

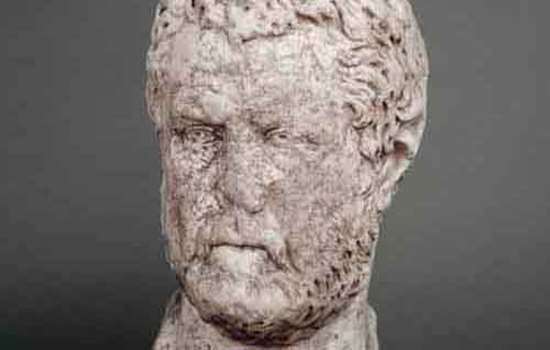

The particularly fine villa at Lullingstone was rather different: although it has a large barn, there is little evidence of other farm buildings, and it may not have belonged to a farming family. Carved marble busts found there of Publius Helvius Pertinax, governor of Britain in AD 185–6, and his father, suggest that Lullingstone may have been the governor’s country residence.

The link with Pertinax serves to emphasise that, while some villas may have been the homes of successful farming families – some of whom were probably descended from pre-Roman noble families – others were associated with those at the top of Romano-British society. These were people of great wealth and power.

PLACES OF WORSHIP

Villas may have been built partly for showing off, but they also had a religious aspect. Religious and everyday life in Roman Britain were not separated as they are today, and all villas had domestic shrines.

Some may even have been religious centres for a wider area: Great Witcombe, for example, may have been the centre for a pagan water-cult, while Lullingstone provides some of the most important evidence from Britain for Roman-period Christianity – a room specifically devoted to Christian observance.

END OF AN ERA

But eventually, the comfortable life of the villa owners of Britain came to an end.

Those villas that were successful farms had depended on being able to sell their produce, and as the cash-based economy gradually declined towards the end of the Roman period, the market for the products of villa estates suffered. We can see a decline in standards at many sites: sometimes, for example, the mosaic floors in richly appointed rooms might be ripped out to house corn-dryers.

As the buildings gradually declined and decayed, in the later 4th and early 5th centuries, the opulent villa lifestyle disappeared with them.

Roman Stories

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Landscape

What kind of landscape did the Romans find when they conquered Britain, and what changes did they make?

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.