Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods (like salt or milling stones) with neighbours or more distant communities. This had been the case before the conquest, and would be for many years after it.

SUPPLYING THE ARMY

But the only possible means of meeting the supply requirements of the immense army in Britain was the development of a money economy. This was driven by military pay and long-distance trade.

Very little evidence of commerce survives in the archaeological record, except for pottery, which does not rot and could not be recycled. So for the most part, we have to imagine the foodstuffs, livestock, textiles and other perishable goods that would have formed the bulk of consignments.

HOME AND ABROAD

During the conquest period the Roman army imported samian ware and other fine pottery from Gaul, and made humbler coarsewares itself. Imports arrived via the province’s trading ports, such as London – which grew rapidly into one of the largest Roman cities north of the Alps.

By the AD 120s the army on Hadrian's Wall was using pottery produced by the industry of southern and midland Britain, as well as Gallic imports. British landowners and their workers, as well as economic migrants and merchants from overseas, had joined in the military supply chain.

Britain’s cities also consumed Roman-style pottery and other goods, and were centres through which goods could be distributed elsewhere. At Wroxeter in Shropshire, stock smashed into a gutter during a 2nd-century fire reveals that Gaulish samian ware was being sold alongside mixing bowls from the Mancetter-Hartshill industry of the west midlands.

LOCAL PRODUCTS

There was a gradual shift away from imports from the Mediterranean and Gaul as the local economy grew. Army supply became more and more local, with few imports. A major pottery industry (Crambeck) was established in the north, close to Hadrian’s Wall, and there were large concentrations of potteries in the Nene Valley and Hampshire.

Whereas the army of the conquest had consumed vast quantities of olive oil, imported in amphorae from Spain, the 4th-century army subsisted almost entirely on local produce.

SMALL TOWNS

The growth of the economy of what was a peripheral frontier province was made strikingly clear by the growth of the so-called small towns, a network of settlements that did not have the same status or appearance as a city (or civitas capital).

These urban centres were like nothing in the pre-Roman Iron Age. They had sizeable populations performing well-developed industrial or commercial activities, most commonly ironworking, pottery and glass manufacture. They were places where agricultural products and services could be exchanged.

Some were more obviously agricultural in character: rural villages, essentially, of varying size. The small towns tended to be on the road networks (like Wall in Staffordshire), sometimes originating on the sites of former military bases.

PROSPERITY

By the 3rd and 4th centuries, small towns could often be found near villas. In these towns, villa owners and small-scale farmers could obtain specialist products (like tools) and services (such as a local vet).

Lowland Britain in the 4th century was agriculturally prosperous enough to export grain to the Continent. This prosperity lay behind the blossoming of villa building and decoration that occurred between AD 300 and 350.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Landscape

What kind of landscape did the Romans find when they conquered Britain, and what changes did they make?

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.

Roman Stories

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

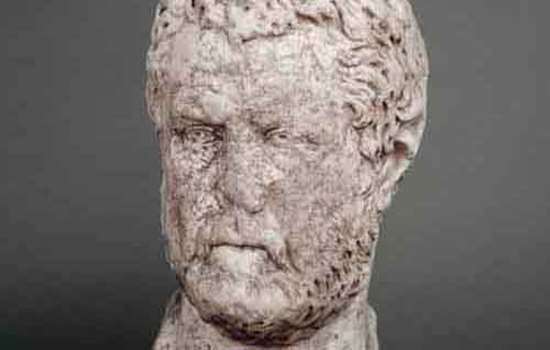

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

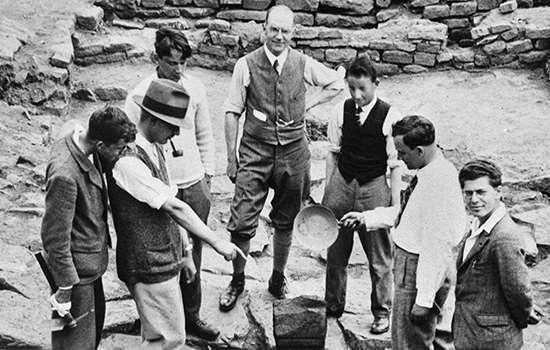

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

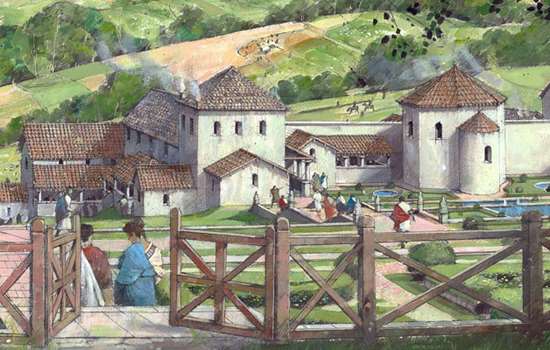

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.