Early Medieval: Art

The Anglo-Saxon period produced highly distinctive art of world-class significance, from the sumptuous metalwork of Sutton Hoo to the glorious illuminations of the Lindisfarne Gospels and the epic poem Beowulf.

METALWORK

Craftsmanship in metal was highly valued by the first Anglo-Saxon settlers. Many early examples survive in the excavated brooches used especially by women to fasten and adorn their clothing.

Even more outstanding metalwork, sumptuously engraved and colourfully inlaid, appears among the astonishing treasure found with the royal ‘ship burial’ of the 620s at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk. Most impressive of all is a solid gold belt-buckle decorated with patterns of interlaced snakes, showing that such patterns are not, as often now described, purely Celtic.

A similarly rich hoard of mid-7th-century metalwork found in Staffordshire demonstrates that such riches and exquisite workmanship were not confined to the kingdom of East Anglia.

CHRISTIAN ART

‘Interlace’ is also a distinctive feature of 7th- and 8th-century illuminated Christian manuscripts. Some of the best known were produced in Northumbrian monasteries, including Lindisfarne Priory. The Lindisfarne Gospels, with their gorgeous ‘carpet pages’, were produced there in the early 8th century.

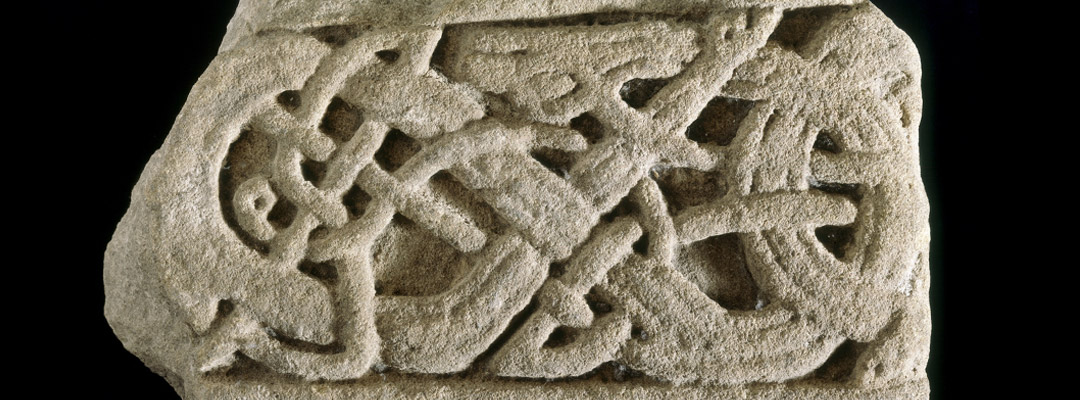

By about 700 English art was essentially Christian art, and it was also manifested in sculpted stone ‘high crosses’. Combining interlace patterns with Christian imagery, some – like the 9th-century Cheshire Sandbach Crosses – were originally painted as well as carved. Others made later, under the influence of Viking/Scandinavian patrons, integrate pagan motifs.

The magnificent 8th-century cross at Ruthwell (once part of the kingdom of Northumbria, but now in Scotland) incorporates what may be the oldest surviving fragment of Anglo-Saxon poetry, part of a Crucifixion poem called the Dream of the Rood.

POETRY

The earliest English poetry was probably not written down at all, but memorised for declamation to a harp accompaniment. The famous epic poem Beowulf, which survives in a single manuscript made in about 1000 but describes much earlier events, begins with a shout for silence in the ‘mead-hall’.

It also depends for its effect on ‘heard’ rather than read devices like strings of alliterating words, and on ingenious synonyms – so ‘the swan’s bath’ is the sea.

The first English poet whose name we know is Cædmon, a humble lay-brother at Whitby Abbey in Abbess Hild’s time (657–80). According to Bede, he was suddenly granted divine power to compose religious verse in English.

Bede’s own Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731) was written in Latin, the universal language of learning. But 150 years later, scarcely anyone in England could write or even understand it – or so King Alfred claimed.

REVIVING A CULTURE

King Alfred of Wessex (r.871–99) set out to rebuild learning in English rather than Latin following the wholesale destruction of English art and culture that occurred during the mid-9th-century Viking depredations.

The king himself was involved in translating basic Latin works into English which he considered ‘necessary for all men to know’, sending copies to every English bishopric. The Alfred Jewel, a masterpiece of English metalwork, is probably the handle of one of the precious word-pointers he sent with them. Alfred’s use of the spoken vernacular (English) language rather than Latin for scholarly works was an innovation, enabling it to develop as a written language much earlier than other European languages.

And English art did revive, despite the further Viking raids which gave rise to the Battle of Maldon (991), the most moving of the old-style heroic poems. Among the revived culture’s glories was opus anglicanum (‘English work’) embroidery, recognised as the finest in Europe (the Bayeux Tapestry represents the apogee of this tradition), and a new ‘Winchester Style’ of illuminated manuscripts.

Now in far closer contact with western European networks, the art of Anglo-Saxon England was still flourishing at the time of the Norman Conquest.

More about Early Medieval England

-

Early Medieval Architecture

Most early medieval buildings were constructed mainly using wood, a tradition which left its mark on later stone-built churches.

-

Early Medieval Arts

The early medieval period produced many examples of highly distinctive art of world-class significance.

-

Early Medieval: Networks

Between the end of Roman rule and the arrival of the Normans, England's relationship with the wider world changed many times.

-

Early Medieval Power and Politics

This period saw the evolution of a nation of warlords into a country organised into distinct kingdoms, eventually unified into the kingdom of England.

-

Early Medieval Religion

Although Christianity in Britain tends to be associated with the arrival of St Augustine in 597, it had in fact already taken root in Roman Britain.

Early Medieval Stories

-

The Viking Raid on Lindisfarne

A devastating Viking attack on the church of St Cuthbert in 793 sent a shockwave through Europe. How did a Christian community at Lindisfarne survive?

-

Who Was St Augustine?

In the late 6th century, a man was sent from Rome to England to bring Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons. Who was St Augustine, and how did his mission succeed?

-

Caedmon, Whitby and Early English Poetry

How Cædmon’s poetic awakening, at the monastery that lies beneath Whitby Abbey, produced one of the first fragments of English verse.

-

Queen Bertha: A Historical Enigma

In 597, St Augustine arrived in England to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Virtually every modern description of this mission mentions Queen Bertha of Kent. But who was Bertha?

-

The Synod of Whitby and the Keys of Heaven

How a decision about the way in which the date of Easter should be calculated was a landmark in the history of Christianity in England.

-

St Hild of Whitby

Hild is a significant figure in the history of English Christianity. As the abbess of Whitby, she led one of the most important religious centres in the Anglo-Saxon world.

-

Two Happy Accidents Reveal Odda’s Chapel, Deerhurst

Read the story of how the chance discovery of a chapel in Gloucestershire has proved crucial to our understanding of Anglo-Saxon architecture.