Prehistory: Art

Art – whether in the form of cave art, rock art, decorated pottery or sumptuous metalwork and jewellery – is one of the most enigmatic aspects of prehistory. It has meanings and functions that are beyond our present understanding.

CAVE AND ROCK ART

Nothing so far discovered in Britain can match the cave paintings of southern Europe, some dating from more than 30,000 years ago.

But in 2003 over 80 engravings and reliefs were identified in caves at Creswell Crags in Derbyshire. There too, in 1876, was found the earliest known English ‘mobile’ figurative art – the strikingly realistic head of a wild horse scratched on a rib bone, between 11,000 and 13,000 years old.

The Creswell cave engravings, perhaps 2,000 years older and the most northerly in Europe, depict deer, bison, horse, and what may be birds or bird-headed people, sometimes cut one above another in multiple layers. It has been suggested that some were intended to be seen by firelight.

Firelight and moonlight may also have enhanced the outdoor ‘rock art’ found at over 2,500 sites in England, mainly in the upland north, north midlands and Cornwall. Complex combinations of shallow ‘cup marks’, and cups within multiple concentric circles (‘cup and rings’) can cover quite large areas of prominent flat rocks; geometric patterns are much rarer.

This rock art is thought to date from the Neolithic and early Bronze Ages (3800–1500 BC), but its meaning and purpose are unknown.

PATTERNS AND POTTERY

The patterning of pottery may also have had meanings which are now lost. Pots, probably first imported in the early Neolithic period, transformed daily life. The first pots are plain, round-bottomed and sometimes bag-shaped. Then two quite different decorated styles evolved: first, round-bottomed Peterborough Ware, decorated with impressions made with bird bones and twisted cords; and then flat-based Grooved Ware, incised with straight lines, diagonals and chevrons.

First made in Orkney in about 2800 BC, Grooved Ware pottery soon spread across Britain. It is particularly associated with feasting and henge monuments, having been found in great quantities at sites such as Hatfield Earthworks (Marden Henge) in Hampshire and Durrington Walls, near Stonehenge.

The same style of incised decoration is also found on rare chalk and stone plaques and can be seen at Stonehenge Visitor Centre alongside other prehistoric artefacts on loan from Wiltshire Museum and Salisbury Museum.

BEAKERS AND BRONZE

There is no doubt about the special status of ‘Beaker’ pots. These distinctive drinking vessels – tall, with narrow necks but wide mouths, often elaborately and individualistically decorated – were popular throughout Europe, and an indispensable accessory for British burials between about 2400 and 2000 BC, in the early Bronze Age.

This pottery style arrived in Britain at the same time as the earliest metals and a new style of individual burial, all suggesting a new fashion and belief system coming from continental Europe.

Beakers are often found in association with copper and gold, and later bronze metalwork, and even with the equipment that produced this revolutionary invention. Soon a tradition of fine bronze-working and goldsmithing evolved, though some of its first manifestations in Britain may have been high-status imports. The native bronzesmiths of Beeston Castle crag in Cheshire were certainly producing sophisticated bronze axe-heads by the late Bronze Age, however.

STATUS SYMBOLS

But the most amazingly accomplished metalwork of the later Bronze Age and Iron Age (800 BC–AD 50) has been found in rivers and bogs, where it was apparently deposited in hoards as gifts to the gods.

It includes bronze ‘parade’ shields engraved and embossed with swirling foliage; a horned helmet; sumptuous bronze scabbards for iron-bladed swords and daggers; twisted gold torcs that would have adorned princely necks; and elaborately decorated horse and chariot trappings like those from Stanwick Iron Age Fortifications in North Yorkshire. For some, these showy status symbols of a warrior elite are the apogee of prehistoric art.

More about Prehistoric England

-

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

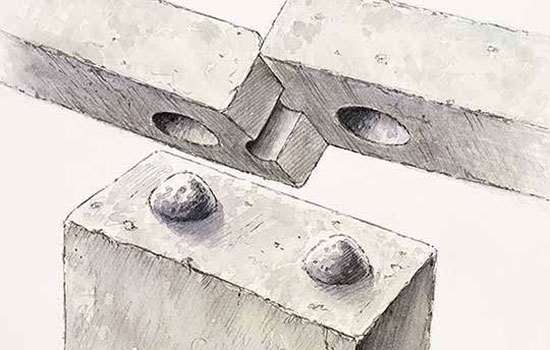

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.