Prehistory: Landscape

Landscape design is nothing new. Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes, often incorporating natural features like rivers, springs and hills.

THE AVEBURY LANDSCAPE

Among the most easily traceable are the ‘ritual landscapes’ developed over a long period in the Kennet valley around Avebury, Wiltshire. The earliest components, dating from about 3650 BC, were Windmill Hill, a causewayed enclosure, and chambered communal tombs including West Kennet Long Barrow.

Over a thousand years later, Avebury Henge and Stone Circles., the largest in Britain, were constructed nearby. Initially it was an immense ditched earthwork ‘henge’, just over three-quarters of a mile in circumference. Soon afterwards its interior was ringed with about 100 standing stones, enclosing two more stone circles.

MAKING LINKS

The henge’s builders connected it to at least two other pre-existing sacred sites. The standing stones of West Kennet Avenue, which extend for 1½ miles, link it with The Sanctuary; Beckhampton Avenue connects it to the Longstones.

The most striking feat at Avebury was the creation between 2400 and 2300 BC of Silbury Hill on the valley floor near the source-springs of the river Kennet. It is the the largest prehistoric mound in Europe, and is still dominant in the landscape today. Although we don’t know why it was built or what it was used for, it may have been the central focus of the whole area.

Stonehenge was also the focus of a ritual landscape. It’s surrounded by other monuments built before and after it, but it’s also linked to the River Avon by a ceremonial avenue about a mile and a half long.

Visual links with natural features were clearly important to monument-builders. For instance, Castlerigg Stone Circle in Cumbria was built in the centre of a kind of natural ampitheatre – a plateau surrounded by mountains.

ENDURING SANCTITY

Landscapes accumulated sacred importance over long periods. Stanton Drew Circles in Somerset were raised over an earlier long barrow; and Arbor Lowhenge in Derbyshire may owe its siting to nearby Gib Hill barrow.

Existing Neolithic landscapes certainly became a focus for raising Bronze Age round barrows. Over 260 survive within a 2 mile radius of Stonehenge. Elsewhere, round barrows were carefully sited on prominent hilltops and ridges. Even with their original gleaming white chalk covering grassed over, and their height much reduced by time, they still dominate the landscape in many upland regions.

DIVIDING THE LANDSCAPE

From about 1700 BC people devoted their energies to creating physical land boundaries: walls, banks and ditches, sometimes on an enormous scale. In lowland areas these have generally been overlaid by millennia of farming. But they are still clearly visible on the moors and uplands where cultivation was later abandoned.

Among the best surviving examples are the Dartmoor ‘reaves’. These long, straight stone walls or earthen banks mark out systems of large rectangular fields – as for example around Grimspound and in the Upper Plym Valley.

During the Iron Age, much more substantial dykes were built, like those at Grim’s Ditch in Oxfordshire, Bokerley Dyke in Dorset, and Argam Dyke in east Yorkshire. These probably defined entire tribal territories.

More about Prehistoric England

-

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

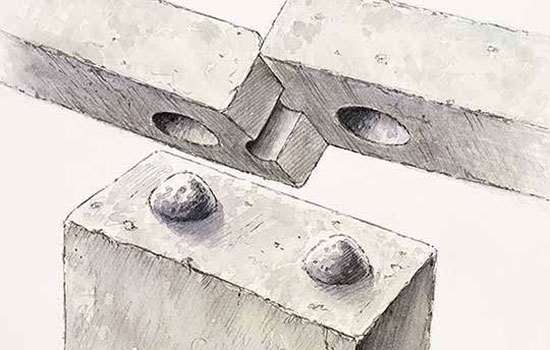

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.