Romans: Art

Rome's success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world, rather than on technological innovation. But the inhabitants of Roman Britain did display creativity in their art.

ROMAN AND NATIVE TRADITIONS

The most accomplished art of Roman Britain would not have appeared out of place in a Mediterranean city. Indeed, some of it may have been executed by artists from abroad.

As with religion in Roman Britain, however, it's common to find artworks that combine Roman with native or Celtic traditions, sometimes brilliantly. For instance, the head of the god Antenociticus from Benwell Temple on Hadrian’s Wall is a fine sculpture in a classical style; but his strange eyes, neck-torque and strikingly patterned hairstyle are Celtic.

PORTRAITS AND SCULPTURE

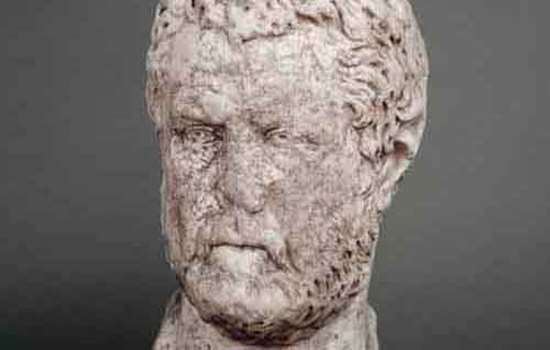

There are several other Romano-British examples of the realistic portrait sculpture for which Rome was renowned. The two marble portrait busts found at Lullingstone Roman Villa in Kent are among the most notable. Much surviving sculpture derives from cult statues of deities, often of great beauty, like the heads of Serapis and Mithras from the Walbrook in London.

The headless oriental goddess Juno Regina at Chesters, on Hadrian’s Wall, with her exquisitely depicted drapery, is either the work of a local sculptor who used an eastern copy-book, or possibly the work of an artist who had travelled from the East.

Relief sculpture on more everyday items such as tombstones, temple reliefs and building inscriptions varied immensely in quality across the province, and is always more commonly found at military sites than at civilian ones.

MOSAICS AND WALL-PAINTINGS

Mosaics, on the other hand, hardly ever appear in military contexts, but are a feature of towns and villas. Polychrome designs are a particularly striking characteristic of 4th-century examples.

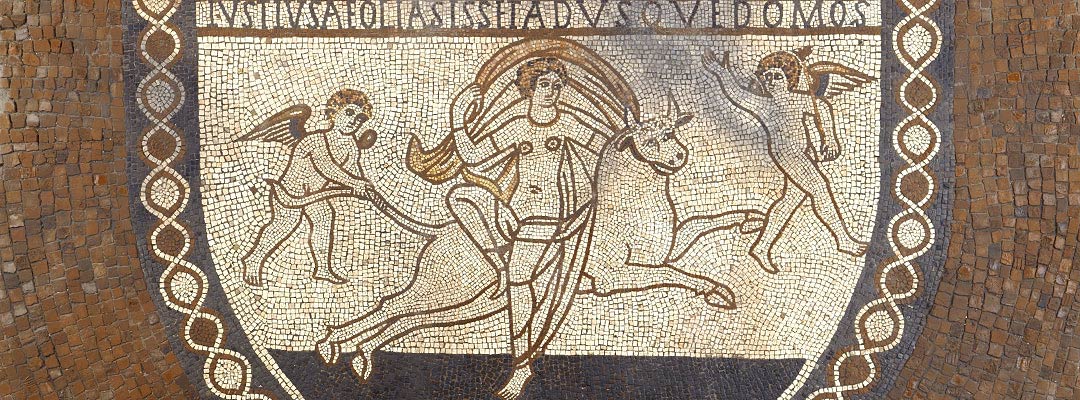

Again there is a great range in quality. A good mosaic of the 4th-century ‘Cirencester’ school of craftsmen can be seen in the great Cotswold villa of North Leigh, while Lullingstone offers an arresting mosaic depicting Europa and the Bull.

Such scenes from classical mythology and literature were the staple subjects of mosaics throughout the empire, and reflect the desire of the owner to be recognised as a leisured landed aristocrat with literary interests. Even the northern city of Isurium (Aldborough, North Yorkshire) has fine polychrome mosaics, once depicting the Muses and the story of Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome.

Painted wall plaster was a feature of all high-status buildings (in military as well as civil contexts). It tends not to survive, but striking examples have been found at Verulamium (St Albans) and, once again, at Lullingstone. The rare surviving 4th-century Christian scenes found there suggest that a part of the villa became a place of Christian worship.

METALWORK

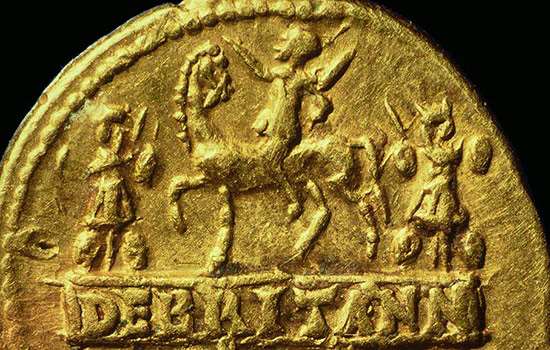

Many smaller metal objects, such as statuettes and miniature shrines, are of high artistic quality, but it is sets of tableware that offer some of the most spectacular examples of the Roman silversmith’s art. They survive because they were hoarded in times of desperation or emergency towards the end of the Roman period, and never recovered.

Often this tableware incorporates Christian symbolism. Some pieces, however, such as a magnificent silver dish found at Corbridge, near Hadrian’s Wall (the ‘Corbridge Lanx’), feature pagan rather than Christian scenes, showing that classical motifs continued to be valued in the Christian empire.

Roman Stories

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.