Caedmon, Whitby and Early English Poetry

How Cædmon’s poetic awakening, at the monastery that lies beneath Whitby Abbey, produced one of the first fragments of English verse – which was certainly not the last work of literature to be inspired by Whitby.

ORDER RESTORED

While riding through the north of England one day in the 1070s, the Norman soldier Reinfrid, a companion of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings, came upon a most dramatic sight at the point where the river Esk meets the North Sea.

High on a headland, and framed by a great void of sea and sky to the east and hinterland to the west, stood the ruins of the Anglo-Saxon monastery of Streaneshalch, founded by Hild, a saint and a princess, in AD 657.

The combined effect of ruins and landscape was so powerful that Reinfrid took holy orders and later returned to live there as a hermit. By 1078 he had founded a small priory of monks there which in time grew into a great Benedictine monastery which we know as Whitby Abbey.

DIVINE INSPIRATION

Four hundred years previously, the site had been the scene of an even more dramatic spiritual and artistic awakening – of Cædmon, the first named English poet.

Cædmon lived at Streaneshalch in about 680, when it was ruled by the great Abbess Hild. According to Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written in 731, Cædmon was a lowly layman, ‘well advanced in years’. He had no artistic leanings whatsoever, and after a feast he would rise from the table and leave whenever he saw ‘the harp coming his way’.

How, then, did this harp-dodging, middle-aged everyman become an accomplished Christian poet of great renown?

One evening, Bede tells us, Cædmon had left a gathering as usual to tend to the monastery’s livestock before retiring to bed. In a dream that night, a man appeared to him asking him to sing about the creation of all things. Cædmon protested that he was unable to do so, but then began to sing verses in praise of God the Creator ‘that he had never heard before’. Thanks to this inspiration, which Abbess Hild pronounced divine, Cædmon was able to listen to a piece of scripture and turn it into verse.

FIRST FRAGMENT

Of the Anglian monastery where Cædmon lived, very little is visible today, although recent excavation has revealed that the site was much more extensive than previously thought – with a large number of timber buildings on the headland (at least 500 metres of which has eroded into the sea since Anglo-Saxon times) and an extensive cemetery, which is now buried beneath the visitors’ car park.

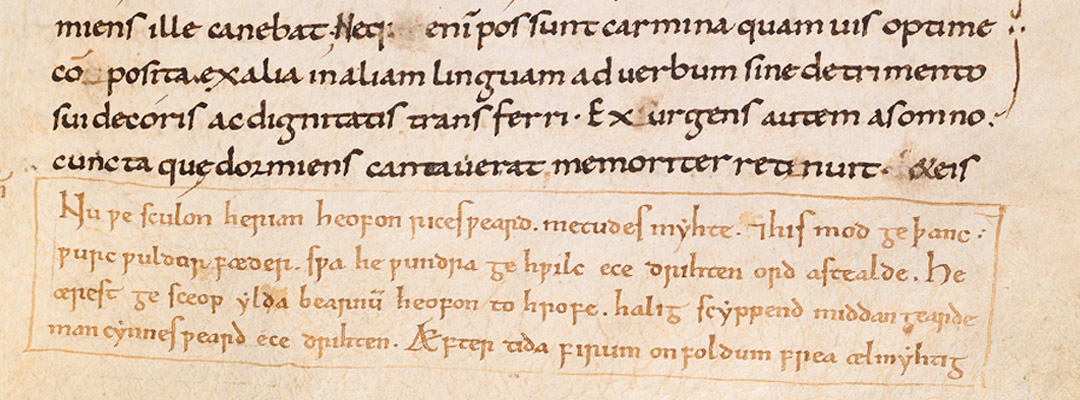

Streaneshalch is thought to have been sacked and destroyed by Danish Vikings in the early 9th century. Cædmon and his poetry survive, however, albeit in fragmentary form, thanks to Bede, who included within the account of his life ‘Cædmon’s Hymn’ – the alliterative praise poem that, supposedly, he learned to sing in his dream. One of the earliest pieces of Old English poetry to survive, it reads as follows when translated into modern English:

Praise we the fashioner now of Heaven’s fabric,

The majesty of his might and his mind’s wisdom,

Work of the world-warden, worker of all wonders,

How he the Lord of Glory everlasting

Wrought first for the race of men Heaven as a roof-tree,

Then made he Middle Earth to be their mansion.

POETIC TRADITION

Whitby’s sublime associations, and its cycles of ruin, were to inspire others too, centuries after Cædmon and Reinfrid. The fact that the Victorian writer Bram Stoker found crucial new locations here, not to mention a name, for his vampire novel Dracula (1897) is only the most famous example.

So it is perhaps unsurprising that one of the earliest English poets – celebrated in Bede’s account, itself one of the first insights into how English verse emerged – found his muse here.

By Tom Nancollas