Early life

Severus was born in Lepcis Magna (Khoms in present-day Libya). His mother’s family were from Italy and his father’s family, the Septimii, were Punic – descended from Phoenicians who had settled in what is now North Africa. While retaining aspects of Punic cultural traditions, including for example language, like many of the Lepcis elite the family had long been Roman citizens, spoke Latin and were inculcated in Roman culture.

By Severus’ time, members of the family had attained senatorial status – the richest and most powerful elite group in the empire. Severus embarked upon a career in public office in an era when people from North Africa were increasingly influential at the higher echelons of the empire.

Severus’ career was at first routine. He entered the senate in AD 173 during the relatively stable reign of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, and held some of the standard offices of the Roman administration, but no important military commands.

He was eventually made consul – traditionally a position of the highest honour – in AD 190 under Marcus Aurelius’ son and successor, Commodus. He was then appointed to the governorship of the Roman province of Pannonia Superior (now in present-day Eastern Europe), giving him command of a large army. This was a timely appointment, as the dynastic stability of the previous decades was about to be shattered.

Route to Power

Increasingly dangerous and unpredictable, Commodus was assassinated in AD 192. Just a year later, his successor, Publius Helvius Pertinax, was murdered at the hands of his bodyguards, the Praetorian Guard, who then sold the title to the highest bidder, Marcus Didius Julianus.

A tripartite war for control of the empire ensued as Severus was proclaimed emperor by his soldiers simultaneously with a rival, Gaius Pescennius Niger, the governor of Syria. With the support of the powerful governor of Britain, Decimus Clodius Albinus, Severus proclaimed himself the avenger of Pertinax and marched on Rome. He had bestowed the title ‘Caesar’ on Albinus, indicating him as his preferred successor.

Severus entered Rome without resistance after Julianus was murdered, before defeating his rival Niger in battle. To consolidate his position, he shrewdly replaced the dangerous Praetorian Guards with soldiers loyal to him, and granted the army various privileges including a pay rise.

Consolidation of Power

The alliance with Albinus did not hold. In AD 195, Severus made his elder son, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (known as Caracalla), ‘Caesar’, and therefore successor. Severus’ wife, Julia Domna, became mater castrorum or ‘mother of the camps’ in an apparent effort to give prominence to his family and establish a dynasty.

This snub to Albinus precipitated a further civil war with his former ally, who proclaimed himself emperor. However, Severus comprehensively defeated Albinus’ legions at the battle of Lugdunum (now Lyon, France). To further secure his position, Severus executed 29 senators who had supported Albinus, before heading off to wage war on Parthia (which was centred largely in what are now Iran and Iraq).

This was the major campaign of his reign and resulted in the sacking of the capital of the Parthian Empire, Ctesiphon, and the creation of the new province of Mesopotamia.

Refurbishment of Hadrian’s Wall

In the period that followed the Parthian campaign, Severus focused on legal reforms and holding games, and he even returned to Lepcis to adorn the city of his birth.

Meanwhile in Britain, his provincial governors conducted a large programme of building works in northern Britain, particularly on Hadrian’s Wall. Under the direction of the provincial governor, Lucius Alfenus Senecio (c. AD 205–8), new granaries were constructed and the defences repaired at Birdoswald Fort. There was restoration of buildings at Chesters and Housesteads and the Wall itself was probably also repaired.

Severus’ role is an important reminder that Hadrian’s Wall evolved over the course of its near 300-year lifespan and that several successive generations of Romans reshaped it.

Arrival in Britain

In AD 208 Severus set out for Britain with a great army, although it is not entirely clear what his intentions were.

The Roman historian Herodian claims that the expedition was precipitated by a call for military aid by the governor in the face of a rebellion. Cassius Dio records that it was prescribed by Severus as an antidote to the squabbling of his sons Caracalla and Publius Septimius Geta, with the ostensible aim of conquering the whole of Britain. However, this policy seems particularly curious given Severus’ recent investment in refurbishing Hadrian’s Wall.

The campaign, nevertheless, was a great commitment of time and resources. In addition to the army (estimated at between 35,000 and 50,000 soldiers) the imperial family – his two sons and the empress Julia Domna – travelled with the emperor. The pomp and bureaucracy of the imperial court came to Britain and for three years the Roman Empire was ruled from York (Eboracum).

Leaving Geta and Julia Domna with the court in York, Severus, now aged 63, and Caracalla, aged 20, led the army north of Hadrian’s Wall and advanced deep into what is now Scotland.

Campaigns north of Hadrian’s Wall

Campaigning was difficult in the rugged terrain of northern Britain, against opponents that avoided the irresistible strength of the Roman legions at set-piece battles. Despite the hardships and heavy casualties, it seems that the British tribes ceded some territory, and victory was declared in AD 209–10, with Severus and his sons assuming the title Britannicus.

But any victory was short lived. A revolt by the Maeatae tribes, who were quickly joined by the Caledonii, was harshly put down by Caracalla. Cassius Dio recorded that Severus told his army that the rebels should be eradicated. Suffering with ill health, before he could join this campaign in person, Severus died at York on 4 February AD 211, having suffered from debilitating bouts of gout for the later years of his life.

His sons would fight for the succession, ignoring his supposed final instructions ‘not to disagree’. After swiftly returning to Rome, a year later, Caracalla murdered Geta and seized the throne.

Legacy in Britain

Although it seems that any territorial gains won by Severus were short lived, the impact of his campaigns is apparent in the archaeology of Roman Britain today.

His army constructed dozens of ‘marching’ camps for temporary protection, in addition to large, more permanent bases such as at Cramond (near Edinburgh). On Hadrian’s Wall, a supply base was enlarged at South Shields to provide a convenient depot for storing goods travelling up the east coast. It has been estimated that the base could have stored food for around 25,000 soldiers.

A smaller supply base was built at Corbridge, a frontier town just south of Hadrian’s Wall, attested by a religious altar dedicated by an official in charge of the granaries.

Severus’ association with the Wall meant that before modern archaeologists proved otherwise, Severus was considered by many in the medieval and early modern period to have been its builder.

The origins of soldiers on Hadrian’s Wall

Those who lived in and travelled to Roman Britain included peoples from the three continents of the Roman Empire. The community of Hadrian’s Wall is a good example.

The majority of soldiers served in regiments originally raised in the north-western provinces corresponding to modern-day Spain, Romania, Germany, France and the Netherlands. An inscription found at South Shields records the presence of a Syrian called Barathes, and Romans of North African origin are well represented in the historical record.

There was a garrison of Mauri (Moors) at the fort of Abellava (Burgh-by-Sands) in the mid 3rd century, and a Mauri freedman (former slave) called Victor was memorialised at South Shields. There is also a tombstone at Birdoswald of a legionary named Cossurtius, who was born in Hippo Regius (in modern-day Algeria).

Learn more about communities on Hadrian’s WallRead more

-

Hadrian's Wall History and Stories

Peel back the layers of 400 years of Roman rule in Britain and explore how new communities evolved at the edge of empire.

-

The People of Birdoswald

Military units travelled across the empire to serve at Rome’s north-western frontier. At Birdoswald it was the Dacians – from modern-day Romania – who lived there the longest and left the deepest legacy.

-

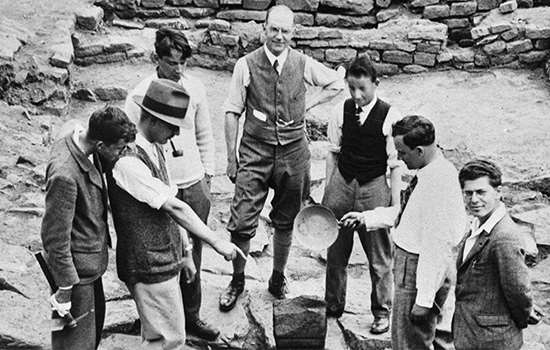

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian’s Wall

The remains of Hadrian’s Wall contain almost 2,000 years of history. Archaeologists are still studying the clues left behind to try to piece together a picture of life at the north-western frontier of the Roman Empire, and how it changed over time.