Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain. These ideas didn’t spring up overnight. Instead, they were probably brought to Britain from the Continent by small groups or even individuals, demonstrating the importance of networks in the period.

ATLANTIC NETWORKS

Sometimes the routes by which new ideas travelled can be traced. The fashion for building ‘megalithic’ (‘big stone’) chambered tombs seems to have originated in Brittany in about 5000 BC, and was then spread by an ‘Atlantic network’ via Ireland, western England, Wales and western Scotland to Orkney. On Orkney, new styles of henges and stone circles developed, together with distinctive ‘Grooved Ware’ pottery. This then spread back south into England and the rest of Britain by about 2500 BC.

But not all new ideas came from beyond Britain. Some prehistoric developments, such as Neolithic linear ‘cursus’ monuments, were probably home-grown.

BOATS

By about 6500 BC rising post-glacial seas flooded ‘Doggerland’, the area that joined Britain to Europe. So new ideas and techniques, like cultivating crops and domesticating animals, must have come by boat. Neolithic dug-out canoes (flat-bottomed log boats) have been excavated around London, and nine from the Bronze Age were found in 2011–12 near Whittlesey in Cambridgeshire.

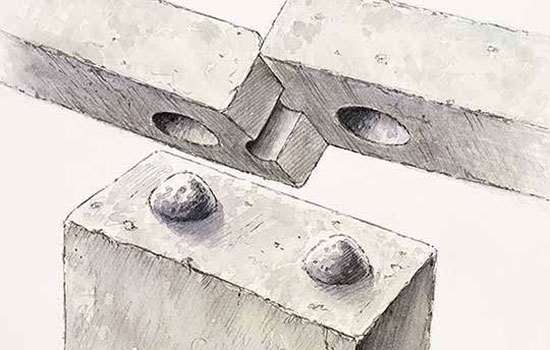

These boats were probably built for inland waterways. But by at least the middle Bronze Age, a new type of much bigger sea-going boat had evolved. These were made of cut oak planks tightly stitched together with yew withies tying them into a watertight keeled hull.

The remains of three of these boats, dating from between 2020 and 1680 BC and up to 16 metres long, were found on the north bank of the Humber at Ferriby. And the Dover Bronze Age Boat, about 9.5 metres long with space for at least 18 paddlers, dates from about 1550 BC.

TRACKWAYS

The prehistoric trackways that were used for long-distance land travel are harder to date. Many follow high ground, avoiding dangerously forested and boggy lowlands. A classic example is the Ridgeway, which may originally have linked the Wash in East Anglia to the Dorset coast (passing Wayland's Smithy, Uffington Castle and Avebury along the way).

Yet marshes too had their own man-made local routeways, which are now coming to light in the Fens and the Somerset Levels. The Somerset ‘Sweet Track’, built of oak planks resting on diagonally set poles, has been tree-ring dated to about 3807 or 3806 BC.

TRAVELLING TO STONEHENGE

A combination of water and overland travel must have been used to bring the bluestones the 156 miles from the Preseli Hills of Pembrokeshire to Stonehenge. If mainly water transport was used, their journey may have been much longer, from the Bristol Channel round the Cornish peninsula and up the river Avon.

The isotope analysis of teeth and bones, which indicates where their owners grew up, shows that some people buried close to Stonehenge had travelled long distances to get there. The Amesbury Archer, buried about 2400 BC, probably came from central Europe, and the Boscombe Bowmen (buried about 2300 BC) from Wales, Cornwall or north-west Scotland.

Some of the cattle eaten at nearby Durrington Walls may have been brought from as far away as Scotland. If so, this was presumably for religious reasons.

AXES AND DAGGERS

Symbolism rather than practical need may also explain why Neolithic stone axe-heads from Cumbria, Cornwall, north Wales and even Northern Ireland are found across England. Similarly, the fine black flint from Grime’s Graves in Norfolk was exchanged or traded over long distances.

Widespread trade networks also brought bronze daggers from Brittany, jewellery made from Irish gold, and precious objects from still further afield to the round barrows of Bronze Age Britain – such as the prestigious weapons and exquisitely worked gold objects found in the Bush Barrow burial near Stonehenge.

More about Prehistoric England

-

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.