Augustinian canons

Kirkham was a monastery – or house – of regular canons, that is to say priests who lived together as a community following a monastic timetable. The regular canons played a very important part in the revival and reform of monasticism in the 11th century.

The Rule of St Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430) governed every aspect of life within the canons’ monasteries. They wore black robes (known as habits) and their day was punctuated by communal services sung in the priory’s church. Time was set aside for reading in the cloister. The canons dined communally, eating a largely vegetarian diet, and slept in a common dormitory.

Because they were all ordained priests, Augustinian canons frequently had spiritual roles in wider society, serving as chaplains and parish priests.

The Foundation of Kirkham

Communities of Augustinian canons were founded across Europe. Their first monastery in England was established at Colchester, Essex, in 1100. Kirkham was one of a number of Augustinian houses founded in Yorkshire during the early 12th century.

The exact date of its foundation is not known, but was probably around 1122. The founder was Walter Espec, a rich and powerful lord. Archbishop Thurstan of York also played a role, consistent with his support for monastic reform in northern England.

The canons occupied an existing parish church at Kirkham, which is mentioned in the Domesday Book. The first prior was William, Espec’s uncle. He had been a canon at Nostell Priory, an Augustinian monastery founded shortly before Kirkham in what is now South Yorkshire. The Kirkham community soon prospered and set about building a stone monastery.

The impact of the Cistercians

In 1132, Espec founded Rievaulx Abbey, about 20 miles from Kirkham and close to his castle at Helmsley, for monks from the austere Cistercian order. The arrival of the Cistercians sent shockwaves through the monasteries of northern England, leading to a clamour for the reform of their communities. Kirkham was swept up in this fervour. Between 1135 and 1140 there was an attempt to transform the priory into a Cistercian monastery as a daughter house of Rievaulx.

The main instigator appears to have been Espec. However, Waldef, prior of Kirkham at the time, may also have had an important role. The plan did not win universal approval within the Kirkham community, however. An agreement survives showing that the canons who did not wish to join the Cistercians were to be provided with their own monastery at Linton-on-Ouse, about 20 miles away. They were allowed to take from Kirkham its crosses, chalices, books and vestments, and also the priory’s coloured glass, which was forbidden by the Cistercians.

Yet for some reason the plan never came to fruition. Kirkham remained an Augustinian monastery. However, Waldef left to join the Cistercians. Ultimately he became abbot of Melrose in the Scottish Borders, where after his death in 1160 he was venerated as a saint.

A thriving community

Despite these events, Kirkham seems to have had good relations with Rievaulx. Surviving books from its library have decorated initials which have close affinities to those found in Rievaulx manuscripts.

Men of considerable talent joined the community at Kirkham. Maurice, prior from about 1169 to about 1177, was learned in Hebrew and was the author of an important theological work which was disseminated to other monasteries.

Gifts made to Kirkham in the 12th century provided the basis for the priory’s wealth for the rest of the Middle Ages. Espec was very generous to the monastery, and other benefactors included members of the knightly class and rich peasants. Most of the priory’s estates were clustered within a 25-mile radius of its gates, and included grazing for sheep, arable, fisheries, mills and woodland. The priory also enjoyed the income from seven parish churches, with canons of Kirkham often serving as their clergy. More distant possessions were in Northumbria and as far south as Leicestershire.

Grants to the priory were frequently made in return for spiritual services, especially burial within its cemetery and the saying of prayers and masses for the soul of the benefactor.

Walter Espec died in 1155. His estates in northern England and patronage of Kirkham passed to the noble de Roos family. The east end of the church at Kirkham was rebuilt on a magnificent scale in the early 13th century. For much of the 13th and 14th centuries, members of the de Roos family were buried there, their tombs prominently located before altars.

The great gatehouse

The priory’s great gatehouse was built in around 1300. The sculpted decoration includes the coats of arms of the de Roos family and several other powerful northern aristocratic families, showing that Kirkham could call upon influential supporters.

There is also extensive religious imagery, including depictions of Christ and the saints, David killing Goliath and St George slaying the Dragon. The gatehouse would therefore have been interpreted as a bulwark against evil, and allegorised as an entrance to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Internal troubles and the impact of war

The monastery was soon to face significant challenges. There are signs that the behaviour of the canons did not always meet the high standards demanded by the Rule of St Augustine. In 1280 Archbishop Wickwane of York criticised the canons’ chant during their religious services, and censured the presence of lay people within the monastic precincts, as well as the admission of jesters and fools into the refectory to entertain the community. The canons were also admonished for leaving the monastery at night to visit friends and relations, and for drinking and other ‘indecent pleasures’.

Several canons are also known to have left the priory for long spells without permission. The most serious offence was committed by a canon called Thomas, who ran away to the priory’s church at Carham, where he set about issuing forged charters. Thomas then used his ill-gotten gains to travel the length and breadth of England and live extravagantly. He was eventually caught and returned to Kirkham. Unrepentant, he was consigned to its prison.

Warfare between England and Scotland in the early years of the 14th century also badly affected the priory. Scottish armies penetrated deep into northern England, and in 1322 nearby Rievaulx and Byland were sacked. Kirkham’s estates in Northumbria were devastated and the priory lost its income from its parish churches in the county. The monastery was plunged into debt, which by 1357 had reached the enormous sum of £1,000. This led to the dispersal of some of the canons to other Augustinian monasteries.

The priory and the local community

Other evidence, however, paints a much more positive picture of life within the priory and shows that it recovered from its misfortunes.

All medieval monasteries have uneven histories, and the criticisms of Archbishop Wickwane were nothing exceptional, especially as he had explicitly set out to find fault. Kirkham’s finances gradually improved and there were extensive building works at the monastery in the 14th century.

The priory continued to enjoy the esteem of the local community, and the canons received numerous generous bequests. For instance, in 1366 Thomas Bucton, a doctor of canon law and a prominent priest in York, left two of his books to Prior William of Driffield. One William Wells asked to be buried in the priory church before the image of the Trinity (to which the monastery was dedicated). He left the priory his ‘best beasts’, 2 shillings and 10 pounds of wax for candles to burn at its altars.

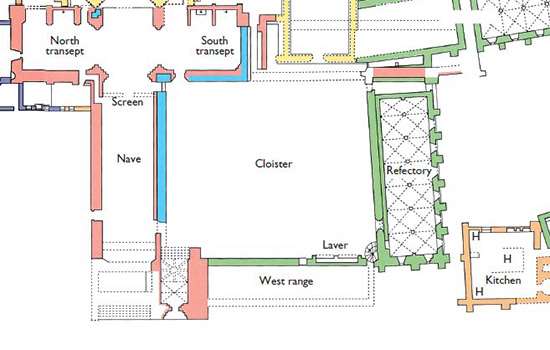

Local people used the nave of Kirkham’s church as their parish church. It was separated from the canons’ church by a screen, which had two doors that the canons could lock. The parish church had its own bell tower. There was a font, used for baptisms, which was replaced in the mid 15th century. The nave also accommodated a free school. Marriages were celebrated at its altars. Local people sought burial within its walls and cemetery. The parish church therefore looked after its parishioners from cradle to grave.

However, in the middle of the 15th century the canons moved parish worship to a specially built chapel close to the priory’s gate. The reasons were reportedly the convenience of the parishioners; to prevent lay people disturbing the canons during their services; and to protect the monastic community from infection with the plague, which was then raging.

Dissolution

Kirkham’s community continued to flourish. Two of its priors were admitted to the prestigious Corpus Christi Guild at York and the priory was still receiving generous bequests well into the 1530s.

However, Kirkham could not escape the religious changes of the reign of Henry VIII and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. A valuation of church property conducted in 1535 found that the priory had an income of £269. It was therefore spared during the first round of monastic suppressions in 1536, which targeted ‘lesser monasteries’ with incomes below £200 a year.

Kirkham’s inevitable end came in 1539. On 8 December the prior and 17 canons signed the deed surrendering their monastery to the king. They left with pensions ranging from £50 a year for the prior to £2 for the novices. Many settled in the local area and remained in close contact, remembering one another in their wills. Two even requested burial within their former church.

King Henry’s commissioners stripped everything of value from the priory. The Crown sold the site in 1540 to the courtier Henry Knevett. Building stone was purportedly removed for the construction of a local manor house. An early 18th-century engraving of the priory shows that it was already heavily ruined.

Recent history

Rediscovery of the priory started in the 19th century. Sir William St John Hope, a leading authority on medieval monasticism, excavated the east end of the church. The site was then in private hands, and photographs show the ruins overgrown with ivy, and the cloister laid out as a tennis court.

However, the historical and architectural importance of Kirkham was such that shortly after the First World War its custody was transferred to the Office of Works, a forerunner of English Heritage. The ruins were stabilised and the priory became a tourist attraction, aided by a local railway station and two nearby boatyards with cafes and shops.

During the Second World War, Kirkham was used by the military for testing equipment in preparation for the D-Day landings in 1944. Prominent visitors to the top-secret base included Prime Minister Winston Churchill and members of the royal family.

The priory is now cared for by English Heritage. Visitors still enter the site through its spectacular late medieval gateway, a tangible reminder of the religious and social worlds that shaped the lives of the canons who lived and prayed there in the Middle Ages.

Further reading

J Burton, Kirkham Priory from Foundation to Dissolution (York, 1994)

J Burton, The Monastic Order in Yorkshire, 1069–1215 (Cambridge, 1999)

G Coppack, S Harrison and C Hayfield, ‘Kirkham Priory: the architecture and archaeology of an Augustinian house’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 148 (1995), 55–136 (subscrition required)

S Harrison, Kirkham Priory, English Heritage guidebook (London, 2000) (buy the guidebook)

W Page, ‘Houses of Augustinian canons: priory of Kirkham’, in Victoria County History: Yorkshire, vol III, ed W Page (London, 1974), 219–22

Find out more

-

Visit Kirkham Priory

Idyllic riverside ruins with a surprising recent history

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of the priory to discover how the monastic buildings developed over time.

-

A Mini Guide to Medieval Monks

Learn how to tell Cistercians from Carthusians with this handy animated introduction to the main medieval monastic orders.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.