ARKWRIGHT, Sir Richard (1732–1792)

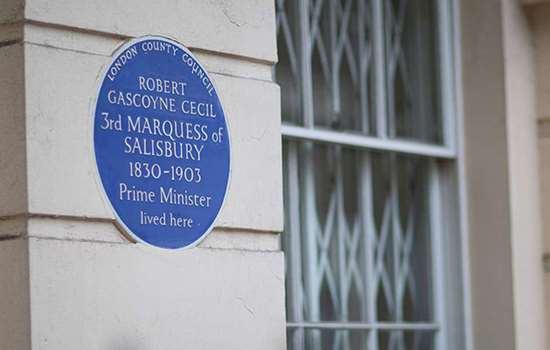

Plaque erected in 1984 by Greater London Council at 8 Adam Street, Charing Cross, London, WC2N 6AA, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Industrialist, Inventor

Category

Industry and Invention

Inscription

SIR RICHARD ARKWRIGHT 1732-1792 Industrialist and Inventor lived here

Material

Ceramic

Industrialist and inventor Sir Richard Arkwright is best known for developing the cotton-spinning machinery that revolutionised the manufacture of cotton in Britain. His name is most strongly associated with Lancashire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire where his cotton mills were based, but some of his final years were spent living at number 8 Adam Street in Charing Cross.

Inventor

Born in Preston, the son of a tailor, Arkwright began his career as a barber and wigmaker, settling in Bolton in 1750. In 1767 he met clockmaker John Kay, and together they developed a roller spinning machine that revolutionised the manufacture of cotton and was eventually patented by Arkwright in 1769. In 1768 Kay became indentured to Arkwright, but he was dismissed in 1772. He appeared in court against Arkwright during his patent trials in the 1780s (see below).

During the 1770s Arkwright put his pioneering device into operation, setting up cotton mills in Nottingham and Cromford in Derbyshire. In 1775 he patented certain instruments and machines for preparing silk, cotton, flax and wool for spinning, in an attempt to monopolise the cotton industry. As business boomed in the second half of that decade, he set up mills in Bakewell, Wirksworth, Litton, Rocester in Staffordshire, and Manchester.

The cotton industry

Arkwright later became known as the ‘father of the factory system’. This system not only saw products produced by machines but also demanded that workers kept pace with them. While initially novel this was to become the norm as the industrial revolution progressed.

Raw cotton for Britain’s mills was imported from the Americas, where it was grown and harvested under inhumane conditions on plantations by enslaved people who had either been forcibly transported to the Americas as part of the transatlantic slave trade or who had been born to enslaved women and so were enslaved from birth.

The machinery in Arkwright’s mills allowed vast quantities of raw cotton to be processed quickly and cheaply, increasing productivity and profits. But those who worked in Arkwright’s mills – some as young as nine years old – often endured long hours, danger and poor pay. The working conditions of the millworkers eventually provoked criticism and the workers themselves began forming societies and unions to represent their own interests. Ultimately legislative changes were enacted to improve conditions.

London and the patent trials

Arkwright was eventually confronted by industrialists willing to challenge the monopoly that his patents gave him. Keen to see his interests protected, he took legal action against those using them without a licence. From 1781, he became involved in a series of trials regarding his various patents, which he tried rigorously to enforce. The trials drew Arkwright to London and he spent much of the last five years of his life living at 8 Adam Street, ideally situated close to the lawyers in the Inns of Court and the law courts at Westminster Hall. Within view of the house was the Society of Arts, the Secretary of which – Samuel More – was among those who spoke on Arkwright’s behalf at his lawsuits.

The trials continued until 1785 and the courts heard claims that Arkwright had stolen the idea for his spinning machine from others such as Kay. The cases were finally settled against Arkwright and his patents were set aside. Although Arkwright was unsuccessful in defending his patents, his business remained extremely lucrative and he made large profits in the 1770s and 1780s. He was knighted in 1786, and by the time of his death in 1792 he was an extremely wealthy man.