HORSLEY, Sir Victor (1857-1916)

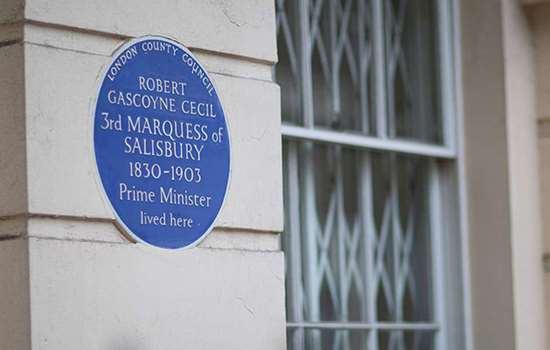

Plaque erected in 2015 by English Heritage at 129 Gower Street, Bloomsbury, London, WC1E 6AP, London Borough of Camden

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Neuroscientist and social reformer

Category

Medicine, Philanthropy and Reform

Inscription

Sir VICTOR HORSLEY 1857-1916 Pioneer of Neurosurgery and Social Reformer lived here

Material

Ceramic

The pioneering neurosurgeon and social reformer Victor Horsley – who also took a leading part in the eradication of rabies from the UK – has a blue plaque close to University College Hospital, on Gower Street.

The first neurosurgeon

Victor Horsley has been called the world’s first neurosurgeon. Before 1890, no other practitioner was more successful in undertaking brain operations: among his operating ‘firsts’ was the removal of a tumour from the spinal cord in 1887.

He also co-developed the Horsley-Clarke stereotaxic apparatus, which enabled the accurate pinpointing of a particular area of the brain for treatment. In terms of its significance to neurosurgery, this invention is comparable to that of the telescope and microscope. Another of Horsley’s innovations was an antiseptic compound of beeswax and almond oil – known as ‘Horsley’s Wax’ – which is still used to stem bleeding from cut bone.

Thyroid treatment and eradication of rabies

Horsley played a leading part in the eradication of rabies in Britain, chairing the Society for the Prevention of Hydrophobia and acting as secretary to a government committee of investigation in 1886. Taking his cue from Louis Pasteur, Horsley advocated the muzzling of dogs, and of strict quarantine measures for those brought into the country. His determination to press these measures – despite objections from the Dog Owners’ Protection Association – led to the UK being declared rabies-free in 1902.

It was also Horsley who founded the modern study of the thyroid gland in Britain, which paved the way for modern treatments of the underactive thyroid, as well as other thyroid disorders.

Horsley and Gower Street

Horsley spent most of his life in London, and as a child lived in the same Kensington house that bears a plaque to Muzio Clementi. Horsley moved to 129 Gower Street in November 1882, while he was a house surgeon at University College Hospital (UCH). A two-bay terraced house, number 129 is Grade II listed and now forms part of a medical students’ hostel. Another former resident was Louis Kossuth.

Horsley brought friends here for tea: the landlady Emma Durrant was, he said, ‘accustomed to great eccentricity in the way of suddenly providing [tea, but] likes to know beforehand.’

His association with UCH, where he first trained, was career long, culminating in a professorship. He also worked at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic in Bloomsbury Square, where his consultancy was, in 1886, the first in the world devoted entirely to the brain.

By all accounts Horsley’s bedside manner was excellent, but he was less charming with fellow professionals. He used the phrase ‘my dear idiot’ as a term of endearment. He once dismissed the Society of Apothecaries as ‘a handful of city grocers who have not a particle of medical education’ and was inclined to refer to colleagues who drank socially as ‘drunkards’ and ‘alcoholics’. Despite all this he was successful in pushing a number of medical reforms, notably to the General Medical Council.

Gower Street is the address where he first set up his ‘brass plate’ of medical practice. It was also while living here that he secured election to the Royal Society of Surgeons and became engaged to his future wife Eldred, to whom he was devoted. He moved out in 1885 and spent most of the rest of his life at 25 Cavendish Square, a house that has since been demolished.

Social reform and war service

Knighted in 1902, Horsley reduced his surgical commitments from 1906 to campaign in support of women’s suffrage and sex education, and to highlight the dangers of alcohol. Twice he stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a Liberal, supporting Lloyd George’s health insurance reforms – a stance that put him at odds with many in the medical profession.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Horsley – then aged 57 – volunteered for active service. Sent to what is now Iraq, he fought hard to improve conditions for the care of wounded and diseased troops, but died of heatstroke on 16 July 1916 at a military hospital at Amara, near Baghdad.

Read more about Sir Victor Horsley at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the British Medical Journal.