Walden Abbey

The large manor of Walden was held after the Norman Conquest of 1066 by the de Mandeville family, the Earls of Essex. On it they established the castle and later town of Walden (now Saffron Walden).[1] In 1139 Geoffrey de Mandeville founded a Benedictine priory (elevated to the status of an abbey in 1190) at Brookwalden, beside the river Cam and the London–Cambridge road.[2] The De Bohuns, subsequent Earls of Essex and of Hereford, were important patrons of the abbey from the 13th to the 15th centuries, and many family members were buried there.[3]

Like all English religious houses, Walden Abbey was suppressed by Henry VIII during the Reformation of the 1530s. It surrendered to the Crown on 22 March 1538 and five days later was granted to Sir Thomas Audley (1488–1544), Lord Chancellor and former Speaker of the House of Commons.

Sir Thomas Audley’s House

By the time of his death Audley, created Baron Audley of Walden, had converted the abbey into his ‘chiefe and capital mansion house at Walden’.[4] A late 18th-century copy of a lost estate map dating to before 1605[5] shows the north range, formerly the church – its east end, including the crossing tower, having been demolished – dominating the other buildings. The monastic cloister arcade is visible on the east range, with a gallery built over it.

Audley’s Franco-Italian early Renaissance-style tomb in Saffron Walden church[6] suggests that, like Sir William Sharrington’s conversion of Lacock Abbey (Wiltshire), Sir Thomas’s work at Audley End may have included architectural elements in the same style.

Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk

Ownership of Audley’s house descended to Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, who was executed in 1572 for conspiring with Mary, Queen of Scots, against Elizabeth I (r.1558–1603). The duke’s second son, Thomas (1561–1626), redeemed the family reputation, gaining Elizabeth's confidence and being created Baron Howard de Walden and a Knight of the Garter.

On the accession of James VI of Scotland as James I of England in 1603, Howard was made Earl of Suffolk and appointed Lord Chamberlain. In 1614 he became Lord Treasurer, but four years later was convicted of corruption, extortion and bribery – the embezzled money had helped to pay off his debts. He and the countess escaped with a heavy fine and retired in disgrace to Audley End, the main cause of their financial problems.

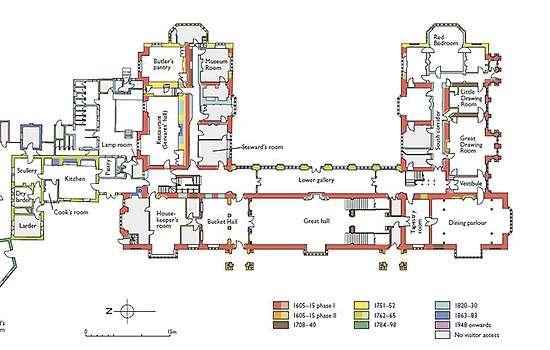

No building accounts survive for Thomas Howard’s rebuilding of Audley End, but both historical events and documentary references place it in the date range of about 1605–14.[7]

Buy the guidebook to Audley EndDesign of the Jacobean House and Landscape

Audley End was the most ambitious house of its period in England. In form and scale it was a royal palace in all but name, intended to accommodate royal visitors on their progresses around the country (James I visited twice in 1614). It had symmetrically arranged state apartments for the king and queen occupying the first floor of the inner court and linked by a long gallery.

Howard had rebuilt the inner court first, working around the footprint of the medieval cloister but making the plan regular and each of the elevations entirely symmetrical. His uncle, Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, and a Flemish mason, Bernard Janssen, are credited as collaborators with Howard himself in the restrained design.

In a second phase Howard added an outer court of lodgings in an altogether more florid style, drawing on French and Flemish Mannerist sources. This is now best represented in the surviving entrance porches on the west front, and was probably to the design of the London surveyor John Thorpe.[8]

All this was surrounded by a formal landscape, approached through a forecourt intended to be flanked by service blocks. These were not completed as intended: only one was built, to the north, probably as lower-status accommodation for the court on a progress, and it was rapidly converted to a stable block.[9]

The privy garden, or Mount Garden, was created on the large level area to the south of the house, overlooked by the king's apartment. It was surrounded by a wall enclosing a raised walk, which overlooked geometric parterres.

Read a description of Audley End House and GardensThe Royal Palace

The 1st Earl of Suffolk’s extravagance and downfall left his successors seriously indebted. The 3rd Earl’s position was eased in 1667, when Charles II bought the house and park at Audley End for £50,000. Of this sum £20,000 remained on mortgage, and the Suffolk family were given accommodation in the northern pavilion of the outer court, as keepers of the new palace.[10]

Audley End’s particular attraction to Charles II, a horse-racing enthusiast, lay in its proximity to Newmarket races. After about 1670, however, neither Charles nor his successors made much use of it. It was by then both old-fashioned and fast deteriorating, despite repairs by the Office of Works.[11]

The house was returned to trustees on behalf of the heirs of the 3rd Earl in 1701, in settlement of the mortgage.[12]

Decline and Demolition

During the first half of the 18th century successive Earls of Suffolk reduced the house to its inner court, employing as their architects John Vanbrugh (1708) and Nicholas Dubois (c.1725).

The 10th and last earl in the direct line married the daughter of a rich brewer, and so could afford to undertake some internal rearrangement,[13] including enclosing the loggia on the south front of the house.

After the 10th Earl’s death in 1745 the estate was divided among the Howard family. In 1751 Elizabeth, Countess of Portsmouth (1691–1762), bought the house and park to add to her inherited share of the estate, for the ultimate benefit of her nephew, Sir John Griffin Whitwell (1719–97).

On the advice of the London builders John Phillips and George Shakespear, she demolished the east (long gallery) range of the house and began to introduce informality into the denuded landscape, planting trees in a more ‘natural’ fashion.

Sir John Griffin Griffin

Sir John, a distinguished professional soldier, came into his inheritance in 1762, having fulfilled his aunt’s condition that he change his surname to Griffin.

The countess’s reduction of the house proved impractical, and Griffin employed the architect Robert Adam to add a stack of galleries behind the great hall to connect the two sides of the house, and to build new kitchen offices to the north. Adam’s principal creative contribution, however, was a new set of ground-floor reception rooms on the south front.

At the same time ‘Capability’ Brown began remodelling the grounds, sweeping away the remains of the formal landscape, with Adam providing designs for the garden buildings, including the Temple of Victory and Palladian (Tea House) bridge. After a quarrel with Sir John, Brown was replaced by Joseph Hicks. Sir John took an active role in devising and directing the works, employing some of the best designers and craftsmen of the day.[14]

In 1784 George III (r.1760–1820) recognised Sir John’s claim to the Barony of Howard de Walden. This event prompted Sir John to create a new state apartment at first-floor level on the south front, opening off the saloon. The east ends of the north and south wings, reduced to a single storey by Lady Portsmouth, were built back up to their original height.

Lord Howard and his second wife, Katherine, were by now respectively a capable amateur architect and decorator, and essentially planned the work themselves. They continued to augment the collections until Lord Howard died in 1797, as well as improving and extending the park.

READ MORE ABOUT JOHN GRIFFIN GRIFFIN AT AUDLEY ENDThe Nevilles

On Lord Howard’s death Audley End and his subsidiary title of Baron Braybrooke passed to Richard Aldworth Neville (1750–1825), a descendant of Lady Portsmouth's first husband. Neville’s eldest son, Richard (1783–1858; from 1825 3rd Baron Braybrooke), a scholar and antiquarian, embarked on the last major reworking of Audley End, after taking over the house from his father in 1820.

The 3rd Lord Braybrooke’s aim was to recover the Jacobean character of the house. Surviving 17th-century elements were repaired and stripped of paint, and new work in the same style was added, but pragmatically much of Adam’s work was retained. His ground-floor reception rooms (except the library) were adapted to form the new state apartment, and a new suite of reception rooms was created in its place on the first floor of the south wing.[15]

Outside, in keeping with the spirit of the interior, 17th-century formality was also recaptured. In the 1830s Lord Braybrooke commissioned the fashionable garden designer William Gilpin to lay out a formal parterre or flower garden on the east side of the house. Lodges were rebuilt in Jacobean style, and there was substantial investment in the estate.

The 20th and 21st Centuries

After the death of the 3rd Lord Braybrooke the house passed to his surviving sons as successive Lords Braybrooke until 1902, when Latimer Neville, 6th Baron Braybrooke, died. From 1904 until 1912 it was let to Lord Howard de Walden, a distant relative, who was attracted by the racing at Newmarket.[16]

Under Henry Neville, 7th Baron Braybrooke (1855–1941), the Neville family retrenched, selling their seat of Billingbear, Berkshire, and bringing its contents to Audley End. After being requisitioned for war use in 1941 Audley End served as the headquarters of the Polish Section of the Special Operations Executive.[17] It was bought for the nation in 1948, the 9th Lord Braybrooke leaving many of the contents on loan.

The emphasis under the Ministry of Works and, from 1984, English Heritage, has been on research, repair and conservation. Recent restoration has focused on elements such as the kitchen garden, domestic offices and parterre, which were maintained until the house ceased to be a family home in the mid-20th century.

About the Author

Paul Drury FSA is an archaeologist and architectural historian, whose interest in applying archaeological techniques (including excavation) to understanding the evolution of Elizabethan and Jacobean great houses began with his work at Audley End in the 1970s.

Find out more about Audley End

-

A COUNTRY HOUSE TECH PIONEER

Discover how John Griffin Griffin installed domestic inventions and comforts at Audley End that were well ahead of their time.

-

Below Stairs at Audley End

What were Victorian servants’ lives really like? Discover the stories of the men, women and children who worked at Audley End House in the 1880s.

-

Capability Brown at Audley End

Find out how England’s foremost landscape gardener fell out spectacularly with Sir John Griffin Griffin, the owner of Audley End.

-

SILENT UNSEEN: THE POLISH SPECIAL AGENTS OF AUDLEY END

During the Second World War, Audley End was used as a training base by the Polish Section of the Special Operations Executive. Discover their incredible story.

-

Description of Audley End

Read a description of this impressive house and its gardens, which have been shaped by various owners over the centuries.

-

Why does Audley End matter?

Find out why Audley End is a site of such value, both for the architecture and contents of the house and for its 18th-century landscape.

-

Collection Highlights

View detailed images of some highlights from the diverse collection at Audley End – from paintings to natural history tableaux.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF to explore detailed plans and elevation drawings of Audley End that reveal how the house has developed.

-

Research on Audley End

Read a summary of the current state of research on Audley End, with details of excavations, investigations and areas for future research.

-

Sources for Audley End

Use this list of written, visual and material sources for our knowledge and understanding of Audley End for further research into its history.

-

BUY THE GUIDEBOOK

The guidebook offers a complete tour and history of the house and gardens, and brings the house to life with stunning photos and historic images.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.