Description of Audley End House and Gardens

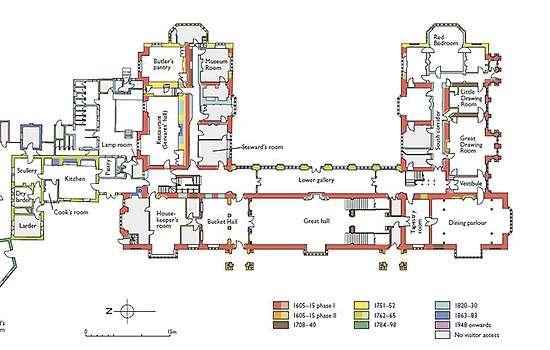

The impressive house that can be seen today is only about a third the size of the vast mansion created in about 1605–14 by Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk. It retains much of its original character, and contains fine Robert Adam and Jacobean revival interiors. The gardens and landscape, shaped by various owners to complement the house, reflect many changes in English garden fashion.

Exterior

The exterior of the house presents a more or less consistent and restrained Jacobean style, derived from its rebuilding by the 1st Earl of Suffolk after 1605, and generally followed by later owners.

The comparatively low great hall occupies the west wing, flanked by the tall pavilions of the north and south wings. In the 17th century these housed matching royal or state apartments at first-floor level, the importance of which is clear from their having the tallest windows.

The royal apartments have identical storeyed porches, added late in Thomas Howard’s building campaign in a much more florid Mannerist style, which was shared by the lost outer court from which they were entered.[1] The round head of the porch door leading to the king’s apartment frames a scene of Mars, god of war,[2] while the north one, leading to the queen's lodgings, has an allegory of peace.

The state apartments were originally connected by a long gallery forming the east range of the inner court. When this was demolished by the Countess of Portsmouth in 1752, its loggia was reset as an open communication gallery behind the great hall. In 1764 a picture gallery and service gallery (the Coal Gallery) were added above on the first and second floors, rising behind the hall.

With the rebuilding of the east ends of the north and south ranges to their full height in 1784–6, the house took on its present shape,[3] supported by a service court hidden behind tall yew hedges to the north.

Interior

The interior has been much altered, both in plan and in detail. The Jacobean great hall retains its volume, roof and richly carved oak screen, although the last was probably originally painted.

High-quality decorated Jacobean plaster ceilings survive in substantial parts of the former state apartments on the first floor.[4] The saloon, originally the great, or presence, chamber of the king’s apartment, has the most notable example, with its mythical sea creatures and ships.

Little survives of the early to mid 18th-century internal modernisation by successive Earls of Suffolk, except the lower screen and stair in the great hall, probably by John Vanbrugh (1708) and Nicholas Dubois (about 1725) respectively.

Two periods now dominate: work of the 1760s and 1780s by Sir John Griffin Griffin, who initially employed Robert Adam, and that of the 1820s by the 3rd Lord Braybrooke. The latter sought to reimpose a dominant Jacobean character on the house, but with a pragmatic approach that saw, for example, the retention of Sir John’s white and gold colour scheme.

Sir John Griffin Griffin’s Contribution

Robert Adam created a suite of reception rooms for Sir John Griffin Griffin in the mid-1760s on the ground floor of the south wing. It represented the height of neoclassical taste, and was executed by the leading craftsmen of the day. The plasterwork was by Joseph Rose, carving and gilding by William and Robert Adair, furniture by Gordon and Tait (much of which survives in the house), and decorative painting by Biagio Rebecca.

When the principal reception rooms were moved back to the first floor by the 3rd Lord Braybrooke (see below), these rooms were adapted as the state apartment. Adam's library, the culmination of the sequence of rooms, was destroyed in order to bring the floor level of the rooms over it down to that of the remainder of the first floor.

The surviving sequence (partly restored in the 1960s) now comprises the dining parlour, the Great Drawing Room and the Little Drawing Room, the last with exquisite painted Roman decoration by Rebecca.

The Gothick chapel at the north-east corner of the house was created for Sir John in about 1768 by John Hobcraft, and survives little altered and complete with its furniture (save for the loss of the organ loft in the 1820s).[5]

In 1785, to commemorate his elevation to the peerage as Baron Howard de Walden, Sir John completed the refitting of the saloon, on the first floor of the south wing, below its Jacobean ceiling.[6] The white and gold panelling incorporates a series of paintings adapted or created by Rebecca, illustrating Sir John’s descent from Thomas, Lord Audley, who created the first house at Audley End in the 16th century.

The 3rd Lord Braybrooke's Contribution

The 3rd Lord Braybrooke’s architectural contribution to the house is most clearly expressed in the new reception rooms that he created in the 1820s on the first floor of the south wing, beyond the saloon. Surviving Jacobean ceilings were carefully retained, even where a dividing wall was removed to create the new dining room.

To the east of the saloon are the drawing room, south library and, across the end of the south wing, the principal library. Here Henry Shaw and Henry Harrison ‘carefully imitated [the individual elements] from examples in different parts of the house’.[7] As throughout this suite of rooms, however, the extension of Sir John’s white and gold colour scheme from the saloon lifts it far above heavy antiquarianism. Formal parterres created beneath the windows completed the ensemble, complementing the neo-Jacobean interiors.

A more conventionally Jacobean effect was created in the great hall: the screen was cleaned of its 18th-century paint, and the panelling was renewed in varnished oak. But this is still an eclectic interior, as it incorporates in the fireplace neoclassical statues from Robert Adam's demolished library alongside old woodwork.

Having decided to make Audley End his principal seat, Lord Braybrooke brought the Neville family heirlooms from Billingbear, Berkshire. His wife, Lady Jane Cornwallis, contributed the best of her family inheritance, including the ancestral portraits now in the great hall and picture gallery.

The Landscape

The features visible in the gardens now are mainly the work of the two designers ‘Capability’ Brown and Robert Adam, commissioned in the late 18th century by Sir John Griffin Griffin to refashion the estate. The site, on flat ground next to the river Cam, flanked by its steep valley slopes, provided Brown with an almost ideal landscape canvas.

The site had been chosen six centuries earlier by the Benedictine monks who founded Walden Abbey. Elements of the monastic landscape survive, including Audley End village and the monastic fish pond, Place Pond, the rectangular plan of which was softened in the 18th century.

Henry Winstanley’s late 17th-century engravings of the ‘palace’ created by the 1st Earl of Suffolk (see Sources for Audley End House and Gardens) show the house as the centrepiece of an extensive formal layout of courts and gardens, organised on an east-west axis.

To the west, beyond the inner court of lodgings (removed in stages throughout the first half of the 18th century) was a vast entrance forecourt, divided by a canalised river Cam, with the London to Cambridge road beyond. The stable block marks its intended north side, although outside the forecourt as completed.

The domestic appearance of this stable block indicates its original use as a range of basic lodgings, but it was rapidly converted by the removal of the first floor and the creation of large doorways in its north side, opening on to a stable yard.[8]

The formal landscape persisted in simplified form until the mid-18th century. The Countess of Portsmouth began to soften it and moved the walled kitchen garden away from the house. Under Sir John Griffin Griffin, ‘Capability’ Brown began the landscape garden that survives today, and Robert Adam designed most of its buildings.

The remaining forecourt walls were demolished to open up the extensive views over the lawn. The canalised river Cam was reworked into a serpentine lake – one of Brown's design hallmarks – and naturalistic groupings of trees were planted to the south and west. The Cedar of Lebanon near the house dates to Brown’s time.

Adam designed the new bridge over the river Cam, now called the Adam Bridge, on the road connecting Saffron Walden to the Newport–Cambridge road. His Temple of Victory, Lady Portsmouth’s Column and Tea House Bridge also survive.

In the early 19th century the 3rd Lord Braybrooke recovered some of the formal elements of the landscape with parterres around the house, and he rebuilt the lodges. In the 20th century the gardens declined, but from the 1980s English Heritage has restored the parterres and other elements, including the kitchen garden.

Footnotes

1. For the Jacobean architecture of the house see P Drury, ‘No other palace in the kingdom will compare with it: the evolution of Audley End, 1605–1745’, Architectural History, 23 (1980), 1–39 (subscription required; accessed 25 Nov 2014).

2. After an engraving by Virgil Solis of Nuremberg: A Wells-Cole, Art and Decoration in Elizabethan and Jacobean England (New Haven and London, 1997), 24–5 and note 7.

3. Thus, consciously or not, referencing the original Jacobean plan of Hatfield House, Hertfordshire, begun in 1611.

4. For their location see P Drury, Audley End (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2014), 48. For the plasterwork in context see C Gapper, Decorative Plasterwork in City, Court and Country, 1530–1640 (updated text from PhD thesis, ‘Plasterers and Plasterwork in City, Court and Country c 1530–c 1660’, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 1998; accessed 10 Nov 2014), which sets out its close connection with the plasterwork at Charlton Park, Wiltshire, built on the Countess of Suffolk’s estate in about 1607.

5. M Sutherill, ‘John Hobcroft and James Essex at Audley End House’, Georgian Group Journal, 9 (1999), 17–25.

6. As his painted inscription on the panelling tells us.

7. R Neville (Lord Braybrooke), The History of Audley End and Saffron Walden (London, 1836; accessed 10 Nov 2014).

8. P Drury and P Smith, ‘The Audley End stable block in the 17th century’, English Heritage Historical Review, 5 (2010), 44–81 (subscription required; accessed 10 Nov 2014). For the originally intended form of the forecourt see fig 44.

Find out more about Audley End

-

HISTORY OF AUDLEY END

Read a full account of Audley End’s long and varied history, from the priory founded on the site in the 12th century to the present day.

-

Collection Highlights

View detailed images of some highlights from the diverse collection at Audley End – from paintings to natural history tableaux.

-

Why does Audley End matter?

Find out why Audley End is a site of such value, both for the architecture and contents of the house and for its 18th-century landscape.

-

Research on Audley End

Read a summary of the current state of research on Audley End, with details of excavations, investigations and areas for future research.

-

Sources for Audley End

Use this list of written, visual and material sources for our knowledge and understanding of Audley End for further research into its history.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF to explore detailed plans and elevation drawings of Audley End that reveal how the house has developed.

-

BUY THE GUIDEBOOK

The guidebook offers a complete tour and history of the house and gardens, and brings the house to life with stunning photos and historic images.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.