Foundation

The continuous history of Barnard Castle begins in the 11th century, after the Norman Conquest of England. But as with many medieval castles, it occupies a site that had been strategically important for millennia. The plateau on which the castle stands commands the crossing point over the river Tees of a major Roman road across the Pennines. This remains an important communications route today.

The first castle was probably established by the Picard knight Guy de Balliol. He had supported King William II in the suppression of a rebellion in Normandy in the 1090s, and received estates in north-eastern England as a reward. Periodically throughout the Middle Ages, the bishops of Durham asserted that they owned the estate in which the castle lay, after a grant in the 9th century.

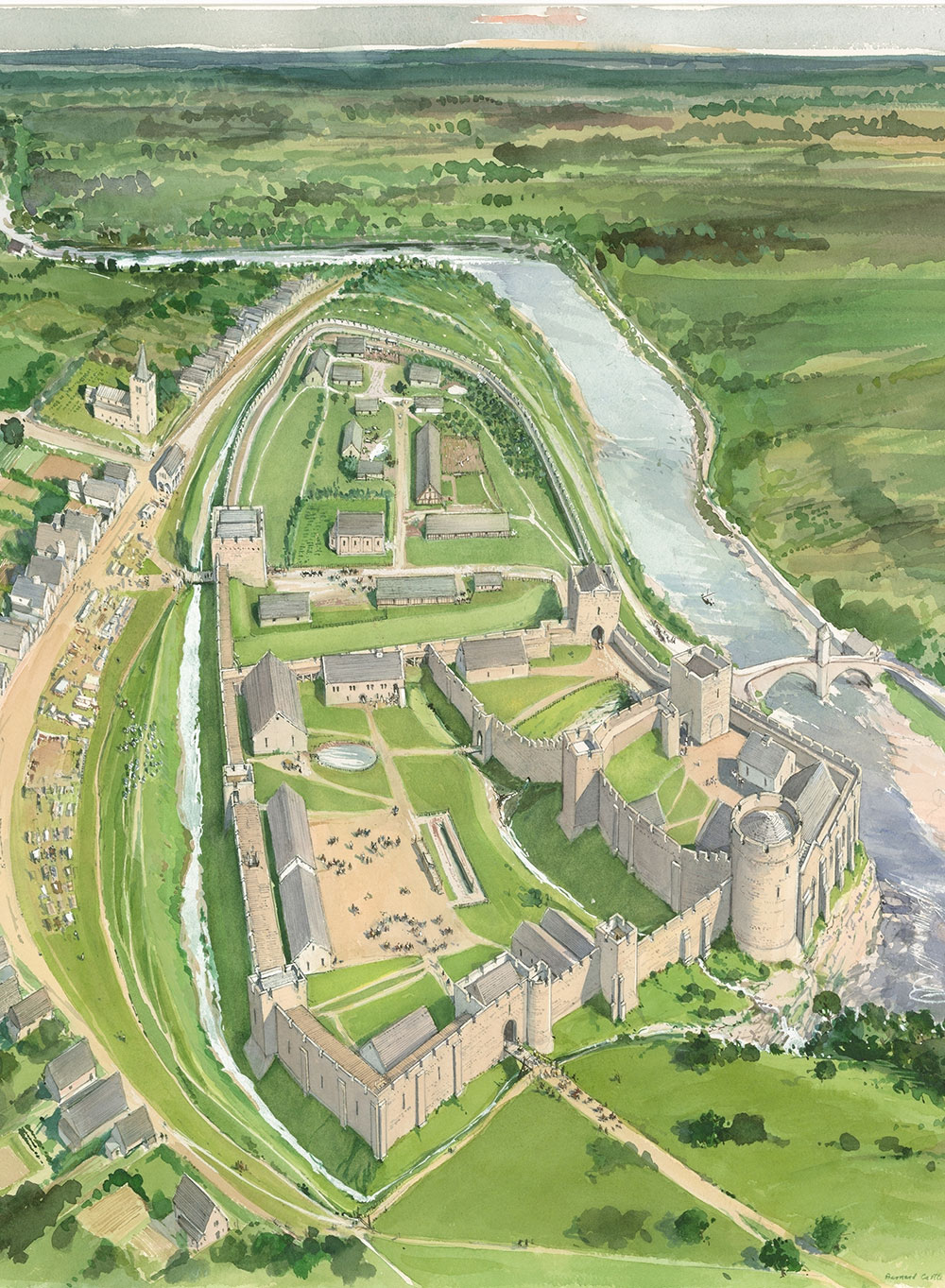

The first castle took the form of a ringwork, an enclosure of ditches and banks protecting the south and eastern sides, with the high cliffs forming the north and western defences. This early castle, whose site is now occupied by the inner ward, contained a stone gatehouse, but was otherwise a timber structure.

Guy de Balliol died in 1133 and was succeeded by his nephew, Bernard, from whom the castle and town derive their name: Castrum Bernardi, or Bernard’s Castle. It was he who enlarged the castle to its present extent, began to rebuild it in stone, and founded the town that surrounds the castle on its south and east sides.

Expansion and redevelopment

Bernard de Balliol died between 1154 and 1159, was succeeded by his son Guy, and almost immediately afterwards by his second son, Bernard II. During the ownership of Bernard II, many of the most important buildings of the castle were constructed. The whole of the surviving Town Ward and Middle Ward, including the remains of the North Gate, Brackenbury Tower and Constable Tower, were built during this period. There is documentary evidence from the end of the 12th century that the castle briefly passed into the hands of the Bishop of Durham as security for debt. This suggests that in his building works at the castle, Bernard de Balliol had over-reached himself.

The modernisation of the castle’s buildings probably continued in the early 13th century under Hugh de Balliol, son of a cousin of Bernard II, who inherited the castle in 1205. Probably from this period came the rebuilding in stone of the hall in the inner ward, and the addition of the great chamber and round tower at its northern end. When King John stayed at the castle in January 1216, after leading a military campaign against northern rebels, these buildings gave him lodgings as stylish as any at his own castles.

Over the 13th century, the castle remained in the hands of the Balliol family, including the famous John and Devorguilla (died 1269 and 1290) – who endowed scholars at Oxford University, formally incorporated as Balliol College in 1282 – and John II, who held the throne of Scotland from 1292 to 1296. With John’s fall from power, Barnard Castle was seized first by Bishop Antony Bek of Durham, and in 1306 by King Edward I. The following year, the dying king bequeathed the castle to Guy de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, whose descendants held it for the next 164 years.

The Siege of 1216

The newly completed castle of the early 13th century was soon to face its first military challenge during a siege in the summer of 1216, in dire circumstances. King John had died, many barons were in open rebellion, and a French army had invaded and occupied much of southern England, while King Alexander II of Scotland moved into northern England, supported by northern barons. These included Eustace de Vescy, brother-in-law to the Scottish king and lord of Warkworth Castle, who suffered personal disaster at Barnard Castle. Coming too close to the castle walls, Eustace was shot by a crossbowman from the garrison, and died of his wounds.

The loss of this champion at Barnard Castle set back the cause of the northern rebels. In the following year, the various invaders and rebels were routed by armies loyal to the new king, Henry III. Barnard Castle was about to enter a period of unusual prosperity and favour.

The earls of Warwick

In 1315, when the heir to the earldom of Warwick was only a baby, King Edward II placed the castle in the hands of John le Irreys (Irishman). Soon after his appointment, le Irreys raided Bowes Castle, abducted the widowed Lady Matilda Clifford, and brought her back to Barnard Castle, where she was raped. Edward II retaliated by sending an army to rescue the lady and deprive le Irreys of his command. Lady Matilda later married a knight in her rescue party.

Thomas de Beauchamp came of age to inherit Barnard Castle in 1329. During his 40 years as lord of Barnard Castle, he modernised the great hall, over a century old, and improved the kitchens and other service buildings in the inner ward.

In 1446, through a failure in the male line of the Beauchamp family, the earldom and estates passed to Richard Neville, husband of the Beauchamp heiress Anne Beauchamp. Richard would be posthumously remembered as ‘Warwick the King-maker’, because of his oscillating support of the Yorkist Edward IV and the Lancastrian Henry VI during the Wars of the Roses.

After his death fighting for Lancaster at the Battle of Barnet in 1471, his estates were divided between his two daughters, Anne and Isabel. Anne was shortly to be married to Richard, younger brother of Edward IV, who became Duke of Gloucester and then, in 1483, King Richard III.

Traces of Richard III

From 1471 until his death in 1485, Barnard Castle belonged to Richard Plantagenet (1452–85), Duke of Gloucester and later King Richard III.

Richard took a particular interest in this castle and undertook several repairs and alterations during his period of lordship. The most obvious survival from his ownership is the projecting oriel window of the great chamber, overlooking the river. The underside of the lintel bears a carving of a boar, Richard’s heraldic emblem. A similar use of this device can be seen on a window of St Mary’s parish church nearby, which contains other features attributed to Richard.

A less tangible memorial is the name Brackenbury Tower, commemorating Sir Robert Brackenbury, an important supporter of Richard, who served as his constable of the Tower of London and died with the king at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

Changing Loyalties

With Richard III’s death at Bosworth in August 1485, the king’s mother-in-law, widow of Richard Neville, surrendered her claim to Barnard Castle to the new Tudor king, Henry VII. The castle was henceforth placed in the hands of keepers, notably members of the Bowes family.

Sir Robert Bowes was keeper of the castle in 1536 during the Pilgrimage of Grace, a popular uprising against Henry VIII and ostensibly a protest against the Suppression of the Monasteries. He had notable success in appearing to support both sides, surrendering the castle to the rebels ‘without a stroke’ and becoming one of its leaders, only to revert to the king’s service and restore royal control in the locality.

In 1569 Sir Robert’s nephew, Sir George, initially stood more firmly in support of the Crown against rebels. It was only after the defections of many of his men and the loss of a water supply that he yielded the castle to superior forces. At his death in 1580, he was commemorated as ‘the surest pillar Her Majesty [Queen Elizabeth I] had in these parts’.

The Siege of 1569

The 11-day siege of Barnard Castle in December 1569, during the ‘Rising of the North’, represents the last significant action in the castle’s history as a fortress. Sir George Bowes (1527–80) resolved to hold the castle in support of Elizabeth I, against the Roman Catholic nobility who wished to replace the queen with Mary Stuart.

The rebels sent 5,000 men to attack the garrison of 700–800. They captured the outer bailey after six days, soon followed by the Town Ward, leaving the defenders confined to the inner ward. Sir George saw increasing numbers of his own men defect to the rebels, and risked running out of water after the rebels destroyed the pipes from a reservoir, though he did order his horsemen to make a sortie and join other royalist forces nearby.

Eventually Sir George was forced to negotiate his surrender with the rebels. Three decades later, it was reported that damage incurred during the siege had not been repaired.

Ruination

The castle, still scarred from bombardment by the rebels in 1569, passed out of Crown control in 1603, when James I granted it to his favourite, Robert Carr, later Earl of Somerset. A later owner, Sir Henry Vane, began to plunder the castle to provide building materials for his seat at Raby. The castle was therefore in a more dilapidated condition than many at the time of the English Civil Wars – its period of usefulness was already over.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, antiquarians and tourists in increasing numbers celebrated the castle for its scenic qualities in its spectacular setting above the Tees, and for its historical associations.

The Barnard Castle Hermit

Between 1841 and 1845, the Round Tower was inhabited by a man describing himself as ‘recluse, antiquary and artist in painting’. In reality, Frank Shields, short and with a bushy beard, had been an ostler (a person hired to look after horses), but inspired by the castle’s history and romantic associations, and dressed in imitation of a monk’s habit, he guided visitors around the castle as its resident hermit. In 1859, after an altercation with a neighbour, he was evicted from the castle and eventually transferred his affections to the ruined Egglestone Abbey.

His story ended tragically. Increasingly obsessed with ghosts, in 1874 he was confined in a lunatic asylum, where he died in 1881.

Later History

The castle’s location at the heart of the town that bears its name means it has never lost its value to the local community. During the second half of the 19th century, it was established as the setting of annual shows for the Agricultural and Horticultural societies.

In October 1896, the ruins were badly damaged in a severe gale, prompting Lord Barnard to organise repairs, later extended to include the remains of the Round Tower and Brackenbury Tower. In 1952, Lord Barnard placed the ruins in the guardianship of the Ministry of Works, the predecessor of the Department of the Environment, and since 1984, English Heritage.

Further Reading

D Austin, Barnard Castle (English Heritage guidebook, London, 1988)

D Austin, Acts of Perception: A Study of Barnard Castle in Teesdale, English Heritage and the Architectural and Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland, Research Report 6 (2007)

J Goodall, The English Castle, 1066−1650 (New Haven and London, 2011)

M Hislop, ‘The Round Tower of Barnard Castle’, in Castles: History, Archaeology, Landscape, Architecture and Symbolism; Essays in Honour of Derek Renn, ed N Guy (Cambridge, 2018), 81–104

M Hislop, Barnard Castle, Egglestone Abbey, Bowes Castle (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2019)

W Hutchinson, The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham, 3 (1794), 229–52

K Kenyon, Barnard Castle, Egglestone Abbey, Bowes Castle (London, 1999)

CM Newman, The Bowes of Streatlam, County Durham, PhD thesis, University of York (1991)

AD Saunders, Barnard Castle (Edinburgh, 1982)