History of Berwick-Upon-Tweed Castle, Main Guard and Ramparts

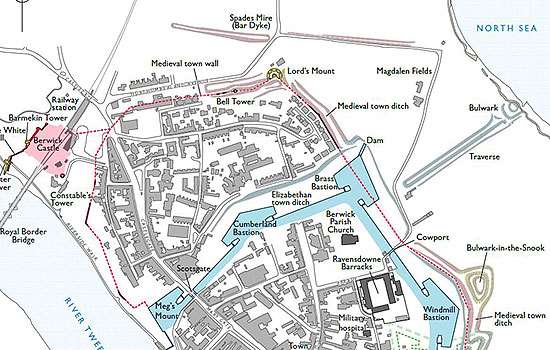

Situated at the mouth of the River Tweed near the border of two kingdoms, the town of Berwick suffered centuries of conflict, as control of the town passed back and forward between England and Scotland until the late 17th century. Each crisis brought repairs and improvements to the fortifications, culminating in the great artillery ramparts begun in 1558. These survive largely intact and make Berwick one of the most important fortified towns of Europe.

The prosperous royal burgh of Berwick had been part of Scotland for more than three centuries when, in 1292, Edward I of England declared John de Balliol King of Scotland in Berwick Castle. Edward’s feudal claims over Balliol soon led to Scottish discontent and to Scotland’s alliance with France. English policy was to make war. Berwick was captured in 1296 but retaken by Robert Bruce in 1318. The town changed sides several times before finally being recaptured by the English in 1482.

High walls and flanking towers, like those built at Berwick, were normally sufficient security against attack and damage from siege engines in the Middle Ages. But the development of gunpowder artillery in the 16th century slowly destroyed the value of traditional fortifications and it was not possible to adapt them satisfactorily.

In western Europe an entirely new kind of artillery defence was developed, of which the Berwick ramparts are an outstanding example.The north-east corner of the town was particularly vulnerable to attack and in 1539–42 a massive circular fortification was erected here, later called Lord’s Mount. In Henry VIII’s reign other works elsewhere around the walls were carried out.

The next development was the introduction of bastioned fortification, found first in Italy at Verona. In 1558 Mary I ordered the English military engineer Sir Richard Lee to Berwick to replace the medieval walls with a bastioned fortification system. In that year Calais had been lost to the French who urged the Scots to attack England's northern outpost.

Bastions are gun emplacements projecting from the wall, enabling defenders to fire outwards across the ditch, or alternatively to repel an enemy attacking the walls to either side. The construction of the new fortifications (which after Mary’s death in 1558 became known as the Elizabethan ramparts) continued as fast as possible but stopped in 1569 before work on the upper ramparts had begun.

By 1568, when Mary, Queen of Scots, fled to England, the Franco-Scottish threat had subsided. As it became clear that James VI of Scotland would succeed Elizabeth I as James I of England, no further work was done to the defences for the remainder of Elizabeth's reign.

The Elizabethan ramparts were modified in the 17th century and the alarm caused by the second Jacobite rising in 1745–6 ensured that they were kept in good order in the 18th century. During the Napoleonic Wars it was proposed to abandon those works that could not be used for the defence of the estuary.

The end of Berwick as a fortified town is marked in the 19th century by the enlargement of Scotsgate, the removal of the Main Guard to the rear of Palace Green and, in 1837, the creation of the pedestrian way along the ramparts.

Description

It is possible to walk the entire circuit of the town fortifications; you may find it useful to follow a route clockwise from Meg’s Mount or, following a visit to Berwick Barracks, from the Windmill Bastion. The walls of the Elizabethan ramparts, faced in grey limestone, stand about 6 metres (20 feet) high. Above the walls the rampart earthwork rises a further 5 metres (16 feet).

Outside there was a broad, deep ditch, or moat, that is now dry. On the other side there was originally a high retaining wall similar to that of the rampart.

Proceeding from Meg’s Mount, notable elements of these fortifications include Cumberland Bastion, which is one of the earliest and best-preserved bastions dating largely from Elizabethan times (though the earthworks above it were constructed in 1639–53); Brass Bastion, defending the north-east corner of the town; Windmill Bastion, a large regular bastion similar to Cumberland; and the Powder Magazine, a gunpowder store surrounded by its own walled enclosure and built in 1749–50.

From King’s Mount to Meg’s Mount, the Elizabethan ramparts were never completed and instead the medieval walls and towers were repaired and modernised.

Against the southern rampart is the Main Guard, a Georgian guardhouse that used to stand in Marygate but was moved to its present site in 1815. Now containing an exhibition on the history of Berwick, it once had a soldiers’ room, a slightly more comfortable officers’ room, and a prison cell for the detention of drunken soldiers, deserters, petty criminals and vagrants.

Berwick Castle and Lord’s Mount

From Meg’s Mount the riverside path leads to the site of Berwick Castle. First recorded in 1160, it was completely rebuilt by Edward I with a strong circuit of walls and an array of impressive buildings, including royal apartments, a great hall and a chapel.

The northern part of the medieval walls can be seen beside the eastern half of Northumberland Avenue. The Bell Tower is conspicuous by its height among the medieval ramparts here. This four-storey octagonal structure was built in 1577 as a watchtower and bell tower, on the foundations of a medieval building.

Lord’s Mount, a great artillery fortification with walls nearly 6m (20ft) thick, was built at the north-east angle of the medieval defences. King Henry VIII, himself a student of fortification, took a personal interest in the drawing up of the plans of these defences (though unfortunately they have been lost).

The lower floor survives, with six casemates for long swivel guns and living accommodation, including a kitchen with well and oven and a latrine. An upper floor containing the captain’s apartments and the crowning parapet was demolished when the Elizabethan defences were begun.

Further reading

Clifton-Taylor, A, Six More English Towns (London, 1981)

MacIvor, I, ‘The Elizabethan fortifications of Berwick-upon-Tweed’, Antiquaries Journal, 45 (1965), 64–96

Paterson, C, ‘The Bell Tower’, Archaeologia Aeliana, 28 (2000), 163–175

Ryder, P, ‘The Cowport at Berwick’, Archaeologia Aeliana, 20 (1992), 99–116