Escape to White Ladies

At 3am on 4 September 1651, a party of 60 Royalist soldiers rode quietly up to the gates of an old converted priory, White Ladies, on the northern border of Shropshire.

It was dark, and they had passed unnoticed through 40 miles of countryside. Among them was a wanted man: the 21-year-old son of Charles I, and newly crowned King of Scotland.

A few hours earlier the Royalist army had been decisively defeated at the Battle of Worcester, where 5,000 of its troops had been killed or captured. The man who would become Charles II had escaped with some of his men, and now required urgent refuge.

Disguise and Rule

At White Ladies, Charles’s coat and breeches were removed and he was dressed in country clothes: green breeches, a leather doublet, a coarse hemp shirt and an old grey hat. Shears were produced and the long, dark royal locks cropped short.

The other troops left and Richard Penderel, the eldest of five brothers summoned to the house, led Charles out to a wood. They stayed there through a long, wet day – reportedly with just a blanket to sit on and a ‘mess of milk and some butter and eggs’ – and planned an escape. They decided to cross the river Severn into Wales and from there sail to France.

As soon as it was dark Charles and Richard set out on foot. Charles practised his disguise, learning from Richard a country fellow’s speech and manner of walking – a ‘lobbing jobsons gate’, as one 17th-century writer describes it. At one point they were forced to run down a country lane and hide behind a hedge after being challenged by the miller at Evelith Mill.

They reached the house of a trusted ally in a town called Madeley, but learned that the Severn was heavily guarded. Their hopes of reaching Wales dashed, Richard and Charles were forced to turn back. They resolved to head out on foot once more under cover of darkness – this time heading for Boscobel House, a mile from White Ladies.

A Secluded Spot

Built by the Giffard family about 30 years earlier, and buried in thick woodland, Boscobel was even more remote than White Ladies. Indeed, it had been designed for privacy. Like many other houses belonging to Catholics persecuted during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, it had hiding places for Catholic priests, known as priest holes.

Exhausted, hungry and soaked through from wading across a river, Richard Penderel and Charles arrived at Boscobel at around 3am on Saturday 6 September. The future king was brought into Boscobel’s parlour by William and Joan Penderel. Charles’s wet stockings and ill-fitting shoes were set by the fire to dry and he was given bread, cheese and ‘a Posset of thick milk and small beer’.

But Parliamentarian soldiers had already raided White Ladies, and Charles and his friends knew that not even Boscobel was safe.

The Royal Oak

Charles consulted with William Careless, another fugitive staying at the house. The king’s account, dictated 30 years later to Samuel Pepys, records their decision:

he told me that it would be very dangerous either to stay in the house or go into the wood (there being a great wood hard by Boscobel) and he knew but one way how to pass all the next day and that was to get up into a great oak in a pretty plain place where we could see round about us for they would certainly search all the wood for people that had made their escape. … [We] got up into a great oak that had been lopped some 3 or 4 years before and so was grown out very bushy and thick not to be seen through. And there we sat all the day.

At White Ladies the pursuing soldiers had been confident of having their man ‘within a day or two’, and as Charles and Careless sheltered in the oak, Cromwell’s troops drew close. The king recalled:

while we were in the tree we see soldiers going up and down in the thickest of the wood searching for persons escaped, we seeing them now and then peeping out of the woods.

The soldiers left and at dusk Charles and Careless returned to the house.

Respite at Boscobel

On that Saturday evening at Boscobel, Charles enjoyed considerably more comfort than he had experienced since fleeing Worcester. One contemporary account reports that he sat down to a dish of chicken, was shaved and had his hair trimmed more ‘as short at the top as the scissors would do it, but leaving some about the ears, according to the Country mode.’ For his bed ‘a little Pallet was put in the secret place’ – the priest hole in the attic.

He stayed at Boscobel for most of the day on Sunday. In the morning, we are told, Charles rose early and, ‘near the secret place where he lay, had the convenience of a Gallery to walk in where he was observed to spend some time in his Devotions.’ Later he came down and helped to fry mutton collops, Major Careless having gone to a neighbouring fold and secretly procured a sheep. Several years later, while in exile in France, Charles spoke of this episode and recalled his skill with the frying-pan at Boscobel with no little satisfaction. Later that day, Charles spent some time in a ‘pretty Arbor in Boscobel garden, which grew upon a Mount and wherein there was a Stone Table and Seats about it.’

The situation was still far from peaceful, however. With the threat of capture looming, Charles left Boscobel that evening with the Penderel brothers to continue his escape.

Into Exile

Charles endured a further six weeks on the run. He went first to nearby Moseley and then to Bentley House, where he changed costumes and left on horseback with the mistress of the house – Mistress Jane Lane – dressed as her servant. They rode to Bristol before Charles made his way through a series of further adventures to Brighton. On the morning of 15 October 1651, he sailed secretly from a creek near Shoreham on a coal brig bound for the Isle of Wight. The captain turned her south, and landed the king at Fécamp, from where he travelled to Rouen, and thence to Paris and the French court. It was to be nine long years until, with Cromwell dead, he could return to reclaim the throne in 1660.

Charles’s courage and spirit at Boscobel, alongside the ingenuity and loyalty of those who hid him, make this one of our greatest adventure stories: an extraordinary and pivotal point in the history of England, celebrated to this day by over 500 pubs named the Royal Oak.

By Nicola Stacey

Explore more

-

Visit Boscobel

Explore the beautiful orchard and gardens, see the descendant of the famous Royal Oak, and hunt out Charles II’s hiding place inside Boscobel House.

-

Visit White Ladies Priory

Visit the ancient priory where Charles II first arrived after his flight from the battle of Worcester.

-

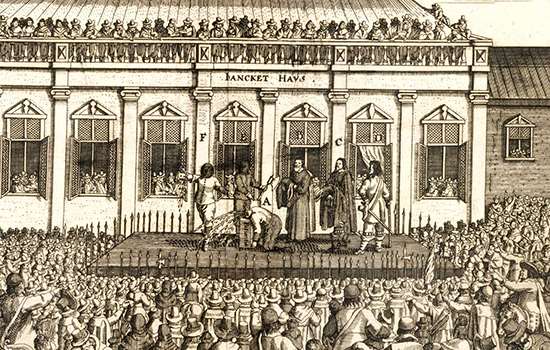

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

-

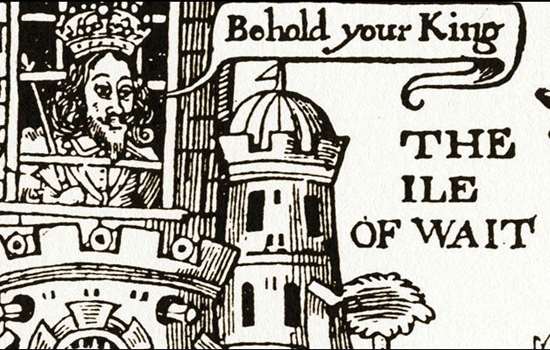

Charles I: a Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle

Learn about Charles I’s time as a prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle, Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.