The Decline of the Country House at Brodsworth Hall

How the precarious survival of Brodsworth’s Victorian interiors reflects the determination of its final owners to preserve a way of life that became almost impossible in the 20th century.

CREATING A COUNTRY SEAT

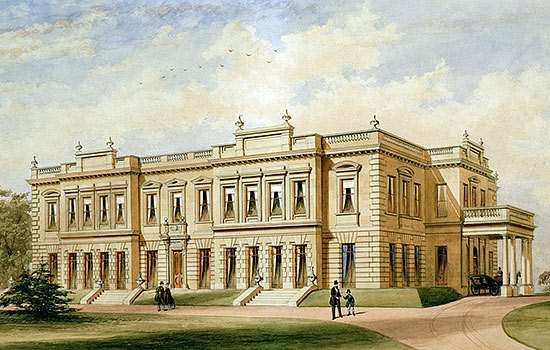

Saved for the nation in 1990, Brodsworth Hall in South Yorkshire still in many ways conveys the assurance and vision of its builder, Charles Sabine Thellusson. He inherited the 8,000 acre estate in 1858, and over the next decade created a country seat in which he could live comfortably and entertain lavishly, particularly during the shooting season.

His conservative 1860s taste still dominates Brodsworth. It informs everything from the Italianate architecture, marbled paintwork, and statuary in the hallways and formal gardens, to its buttoned upholstery, plush carpets, polychrome tiles and tall plate-glass windows overlooking the terraces and sweeping parkland.

MAKING ENDS MEET

A closer inspection, however, reveals a more complex and less confident story. There are patches on the silk wall coverings, electric rather than gas lights, and abandoned rooms.

Even by the time of Thellusson’s death in 1885, it had become increasingly difficult to sustain the house and the lifestyle that went with it through the estate’s farm rents alone. Rents and royalties from the Brodsworth colliery, sunk on land leased from the Thellussons in 1905, brought a few years’ grace before the First World War, which allowed one of his sons to redecorate, introduce such innovations as electric light, an internal telephone and gramophones, and entertain. But the onset of war and economic depression thereafter spelled the end of any sort of extravagance.

The Brodsworth that Charles Grant-Dalton inherited in 1931 badly needed investment, but death duties and military occupation during the Second World War put paid to that. Charles and his wife, Sylvia, retrenched – albeit not quite so far as to give up his beloved cars and sailing boats.

Traces of their economising efforts can be seen in almost every room, in the reduced fireplace openings, the gaps on the walls where sold-off paintings once hung, the threadbare carpets, the curtains that have been cut and turned, and the Formica covering the kitchen tables.

‘HIDEOUS’ HOUSES

The financial pressures and social changes of the 20th century spelled the end for many country houses and estates. They were demolished or sold off in steadily increasing numbers, a process that peaked in the 1950s.

At this time Victorian houses were often seen as especially hideous, impractical and outmoded, which is one reason why Brodsworth’s survival is remarkable. Another is the determination, in their different ways, of both Sylvia Grant-Dalton and her daughter, Pamela Williams, to secure its future. Sylvia, widowed in 1952 and again in 1970, lived on alone in the hall until her death in 1988, with one devoted cook-housekeeper and very few other staff for company.

A STORY WORTH TELLING

Since the 1960s there has been a greater appreciation of Victorian taste and Brodsworth’s special character has become better known. English Heritage took on the house and gardens in 1990 as a gift from Pamela Williams, with most of the contents being purchased through the National Heritage Memorial Fund. Curators have retained as much as possible of the rooms and their contents in order to tell the entire story of the house, and how it was lived in by both family and servants.

This approach, which conserves the house in a manner as close as possible to its state at the end of Sylvia Grant-Dalton’s life, was also influenced by the fragile condition of the interiors and furnishings. Many were so altered from their 1860s vibrancy that they would have had to have been replaced in any restoration of Brodsworth’s original appearance.

So the story Brodsworth tells now is as much concerned with the 20th-century struggle to live in, maintain and adapt country houses designed to be supported by armies of servants, as it is with Thellusson’s Victorian vision.

The electric bar fires in front of marble fireplaces, sinks plumbed in where mahogany washstands were ‘thrown out’ to the servants’ wing because there were no longer any maids to carry coals or water jugs, and even the cracks and flaking paint, can surprise visitors expecting a little escapism into a world of comfort and grandeur.

But the survival of houses like Brodsworth was, and still is, a precarious business. Success stories are usually the result of a coincidence of strong personalities and the will to find a practical financial solution.

By Caroline Carr-Whitworth

Find out more about Brodsworth

-

Visit Brodsworth Hall

Victorian country house frozen in time and award-winning gardens

-

History of Brodsworth Hall

Find out about the history of this mid-Victorian house and gardens, lived in and adapted by the same family over three generations.

-

Description of Brodsworth Hall

The hall survives with many of its original contents, while the gardens have been restored to their 19th-century appearance.

-

Brodsworth Hall collection highlights

Many of the objects at Brodsworth Hall today were among its original furnishings in the 1860s. View some of the highlights.

-

Buy the guidebook

This souvenir guide contains a full tour of the house and includes a history of the Thellusson and Grant-Dalton families, illustrated with many family photos.

-

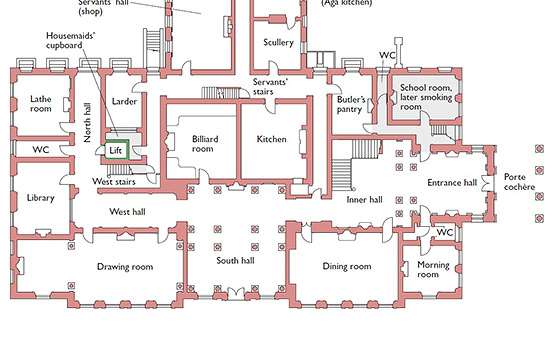

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan of Brodsworth Hall to explore in detail how this Victorian country house was laid out.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.