Henry V and His ‘Pleasance in the Marsh’

How Henry V escaped the burdens of kingship with the help of a secluded lodge across the mere at Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire.

WARRIOR KING

Henry V is the great warrior king of English history, acclaimed for his victory over the French in October 1415 at Agincourt. Contemporary chroniclers portrayed him as an able ruler – a man of unchallengeable authority and self-possession.

Less well known is the image of Henry as a man of culture, patron of writers and composer of music; and another side to this multi-faceted figure is revealed by the retreat he created for himself at Kenilworth Castle.

A HOUSE FOR PLEASURE

At some point between 1414 and 1417 Henry ordered the construction of ‘the Pleasance in the Marsh’ outside the castle. The word ‘pleasance’ (from the Old French plesauns) suggests the idea of pleasure – and this is precisely what it was for.

Although in the 1530s the antiquary John Leland described the Kenilworth Pleasance as a ‘pretty banqueting house of timber’, it incorporated substantial stone elements, including towers at the four corners of its central platform. There was an inner courtyard which had a garden at its centre.

The site where the Pleasance stood can still be visited, north-west of the castle along a public footpath. No buildings survive, but the earthworks are well preserved, and define two concentric moats with a raised bank between them, surrounding a rectangular island of about four acres.

OVER THE MERE

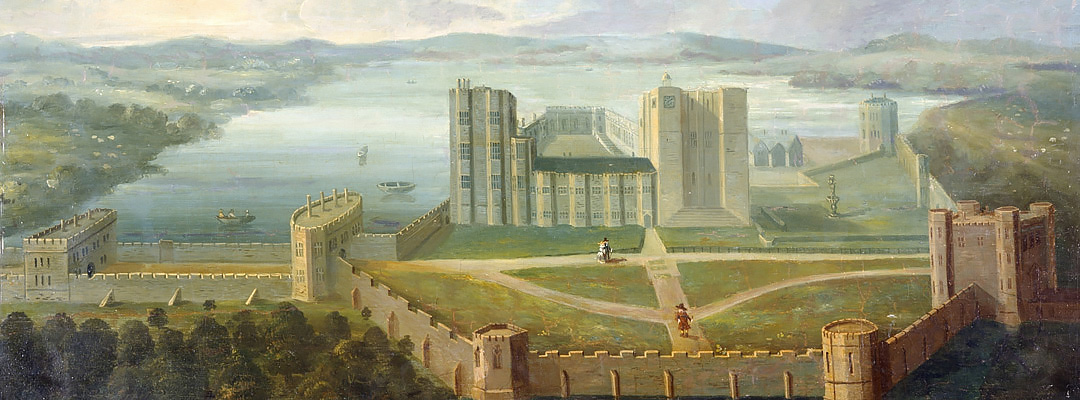

In 1563 surveyors recorded that ‘the prince in times past would go in a boat out of the castle to banquet’. The Pleasance was approached across an enormous artificial lake, the mere, which had surrounded the castle since the 12th century. This transformed the appearance of the castle, the mirror image of which shimmered on the surface of the water, and provided a ready supply of fish and waterfowl.

Henry V’s Pleasance lay at the far edge of the mere, carefully hidden from the castle’s view behind a small spur of higher ground. Here, the king was very definitely off duty. Disembarking at a timber dock in the outer moat, he could have walked around the bank – taking in views of his Pleasance – before eventually crossing a bridge to the central island. And in the garden at the centre, the king enjoyed complete isolation from the pressures of office.

OUT OF SIGHT

The Kenilworth Pleasance was a particularly large and sophisticated example of a type of site which had many parallels in the Middle Ages. In the 12th century, for example, Henry II had created a miniature palace with cloistered courtyards and pools, hidden in a dell close to his manor at Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Allegedly he relaxed there with his mistress Rosamond Clifford, out of sight of his courtiers.

The inspiration for these palaces may have been the retreats of the Norman kings of Sicily, several of which can still be seen in and around Palermo.

Whatever its origins, Henry V’s Pleasance seems to have been short-lived. In 1524 Henry VIII ordered that the buildings on the island be taken down. Some of the timbers were used in a new building within the castle, which retained the name ‘Pleasance’. But by 1568, when Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, began beautifying the castle in preparation for visits from Elizabeth I, this too had been demolished.

CARES OF STATE

It is claimed that during one of Henry V’s stays at Kenilworth in early 1415, ambassadors from the Dauphin of France presented him with a gift of tennis balls – an insult implying that he was only a young man, and thus ‘should have somewhat to play withal, for him and his lords’ – so provoking the campaign that led to Agincourt.

For a medieval king, the pleasures of a secluded garden could provide only the briefest moments of respite.

By Jeremy Ashbee