Significance of Longthorpe Tower

Longthorpe Tower’s outstanding importance lies in its 14th-century wall paintings, which are a rarity both for their mixture of secular, religious and didactic themes, and for their domestic setting. The tower itself has few parallels in southern England, and may reflect its builder’s unusual status.

Domestic Wall-Paintings

The wall paintings were described by EC Rouse in 1955 as ‘the most important domestic mural paintings of the medieval period in England’,[1] and by David Park in 1987 as ‘the major surviving monument of medieval secular wall painting in England, and one of the most impressive north of the Alps’.[2] These claims remain unchallenged.

The painted room is a rare (and perhaps unique) example of an English medieval domestic interior arranged specifically, thanks largely to the positioning of its windows, to show wall-paintings to advantage.

The existence of the scheme may suggest that elaborate painted decoration even in modest 14th-century houses might have been more common than the surviving evidence suggests.[3]

Subject Matter

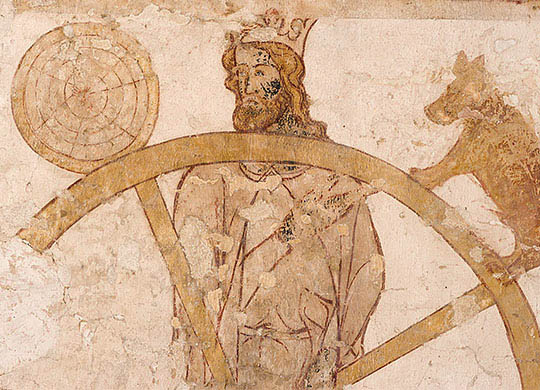

Some of the subject matter of the wall paintings is extremely rare. For the ‘Wheel of the Five Senses’, only two parallels are known: one, a 13th-century example in the Cistercian monastery of Tre Fontane in Rome;[4] the other, a domestic wall-painting of similar date at Constance (south-west Germany), in which animal images of the senses are connected by lines to the relevant features of a crowned seated figure.[5]

Also very rare are significant aspects in the representation of other scenes (such as the ‘Three Living Kings and the Three Dead’), and depictions of St Anthony.

The representation of the musical instruments and how they are being played (such as the saw-edged bow, and the hand positioning) is detailed and convincing, and of interest to musicologists as a primary source.[6]

The Tower and its Builder

Robert I Thorpe, who both built and decorated the tower, occupied an unusual position in medieval society. He was in the service (if at the highest rank) of a great abbey, not a knight but conspicuously rich. The nature of his work at Longthorpe – both showy and erudite – may have been a response to his unusual status.

The attachment of a tower to a house of an otherwise standard medieval plan was common in the north from the early 14th to the late 15th century.[7] Longthorpe, however, is interesting not only in being in the south, where this arrangement was always rare, but for being earlier than any of the northern examples. It was perhaps something of a novelty when built.

Its parallels in date and location are confined to the examples at Little Wenham, Suffolk (c 1265–80),[8] and at Creslow, Buckinghamshire (c 1330).[9] The towers there contained or added to the most private rooms, and are today sometimes called ‘solar towers’.[10] These were too expensive to build just for space, and most were intended, in varying proportions, both to provide real security and bestow the ‘architectural trappings of fortification’,[11] with their connotations of authority, martial prowess and ancient lineage.

Finally, the Thorpes are an interesting (and now well studied, thanks to the work of Robert Kinsey)[12] example of a medieval family who advanced their careers, status and fortune through the legal profession.

Continuing Study

The study of the paintings (particularly the ‘Wheel of the Five Senses’) is, arguably, valuable and unusual in having brought together experts not only in art history, but in the study of political, scientific and philosophical thought, ancient and contemporary, as it existed in the 14th century.

READ MORE ABOUT LONGTHORPE TOWER

Footnotes

1. EC Rouse and A Baker, ‘The wall-paintings at Longthorpe Tower near Peterborough, Northants’, Archaeologia, 96 (1955), 2 (subscription required; accessed 7 July 2015).

2. D Park, ‘Wall painting’, in Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, ed J Alexander and P Binski (London, 1987), 129.

3. ME Wood, The English Medieval House (London, 1965), 401.

4. C Nordenfalk, ‘Les cinq sens dans l’art du Moyen Age’, Revue de l’Art, 34 (1976), 24–5 and fig 13.

5. D Park, personal communication.

6. Dr Alexandra Buckle, personal communication, April 2013.

7. Adam Menuge, personal communication.

8. A Emery, Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500, vol 2 (Cambridge, 2000), 119–22.

9. Ibid, vol 3 (Cambridge, 2006), 82–3; RCHME, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Buckinghamshire, vol 2 (North), (London, 1913), 94–5 (accessed 7 July 2015).

10. Wood, op cit, 76, 166.

11. J Goodall, The English Castle (London, 2011), 6.

12. R Kinsey, ‘Legal service, careerism and social advancement in late medieval England: the Thorpes of Northamptonshire c 1200–1391’, unpublished PhD thesis (University of York, 2009).