Two Happy Accidents Reveal Odda’s Chapel, Deerhurst

How the discovery of an Anglo-Saxon chapel in Gloucestershire, purely by chance, has proved crucial to our understanding of Anglo-Saxon architecture.

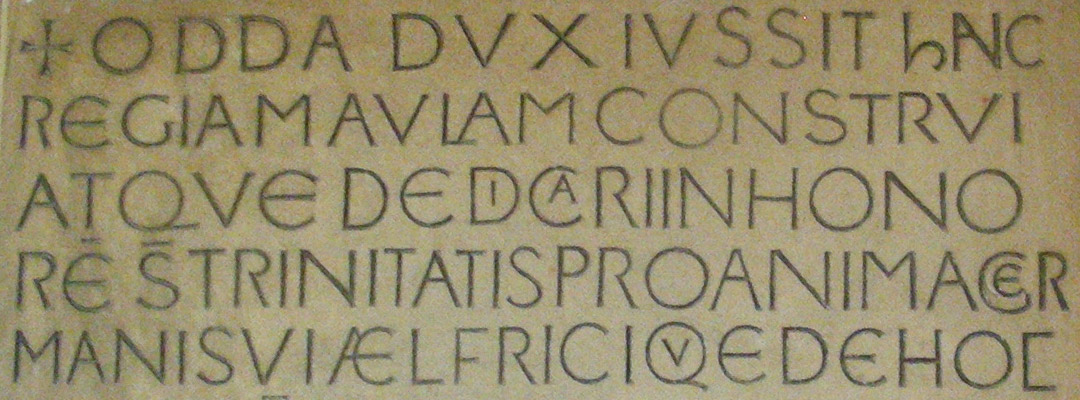

SAXON SLAB

In 1675 Sir John Powell, a local landowner, made a remarkable discovery in his orchard in the village of Deerhurst: a rectangular stone slab bearing a complete inscription in Latin.

The stone still survives, and is preserved at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Translated into English, its inscription reads:

Earl Odda ordered this royal hall to be built and dedicated in honour of the Holy Trinity for the soul of his brother Aelfric, taken up [into heaven] from this place. Ealdred was the bishop who dedicated the building on the second day before Ides of April in the fourteenth year of the reign of Edward, king of the English.

Some of the names mentioned in the inscription have long been well known to historians. ‘Edward, king of the English’ was Edward the Confessor, who reigned from 1042 until his death in 1066: the date of the inscription was therefore 12 April 1056. Odda was a kinsman of the king, sometime entrusted with the government of a large area of south-west England. His brother Aelfric died in 1053 at Deerhurst; Odda himself lived only four months after the dedication, and he too died at Deerhurst.

Much of the rest of its content was rather mysterious, however.

MYSTERY HALL

The greatest puzzle revolved around ‘this royal hall’, the building for which the inscribed stone was evidently made. The detail about the dedication to the Holy Trinity clearly indicated that this was not a domestic hall, forming part of a secular residence, but rather a religious building.

There was a natural candidate close at hand. Deerhurst contains one of the best-preserved and most sophisticated Anglo-Saxon churches in England, now the parish church of St Mary, but formerly part of an important monastery. Initially it was assumed that the inscription referred to the church; but inconveniently the monastery had been founded long before 1056, almost certainly as early as the 7th century. The identity of the ‘royal hall’ remained an enigma.

HIDDEN CHURCH

Then in 1885, while a stone house in the village was being repaired, a round-headed window was discovered behind the plaster of one wall. When more plaster was stripped away, it became clear that this house had once been a church, with a nave and chancel.

The restorers then discovered a further inscription built into a 16th-century chimneystack, unfortunately damaged, but almost certainly reading ‘This altar has been dedicated in honour of the Holy Trinity’. Neatly echoing the text of the Odda Stone, it clearly indicated that this was the building to which the stone slab referred.

The existence of a church and chapel so close together reflects the fact that a precinct which had once belonged to the monastery of Deerhurst was – as documentary sources relate – divided in the 11th century. The southern part then became Earl Odda’s residence. The church that Odda built in the 1050s in memory of his brother was, therefore, attached to his own house. The house eventually expanded, probably after the Suppression of the Monasteries in the 16th century, to absorb the ancient domestic church.

FIXED DATE

Because its date is known, Odda's Chapel has become an extremely valuable fixed point for the dating of late Anglo-Saxon architecture. Some of its distinctive features have usefully been set within the context of wider architectural developments. The double-splayed windows of the north and south nave walls, for example, and the ‘long and short’ quoins of the exterior angles, are features visible on a number of other surviving churches.

Some of the chapel’s features are highly unusual: the slightly horseshoe-shaped internal arch between nave and chancel, and the mouldings on the stones from which the arch springs, have analogues only in churches built in Normandy in the 1060s, some time after Odda’s Chapel, but before the Conquest of 1066.

Quite what this means is uncertain, but it supports a view that the transfer of artistic ideas between Normandy and England was not one-way from the former to the latter, and that it had begun before the Conquest.

Many other churches similarly hidden within later houses may yet be discovered – perhaps as a result of other happy accidents, and with equally fruitful results.

By Jeremy Ashbee