Georgians: Architecture

The classic Georgian building is the Classical country house, standing alone in its own landscaped park. But this is also the period that saw the first steps towards a coherent approach to town planning.

CLASSICAL AND PALLADIAN

Some early Georgian mansions (like Sutton Scarsdale Hall, Derbyshire) continued to adopt the monumental Baroque style popularised in the late Stuart period. But soon purer architectural imitations of Classical Roman and Greek originals – as filtered through the designs of 16th-century Venetian architect Andrea Palladio and the Scottish architect Colen Campbell’s seminal Vitruvius Britannicus (1715–25) – carried all before them.

Ultra-fashionable villas on the fringes of Georgian London led the way. Compact Marble Hill House (begun in 1724) became the model not only for many English mansions but also for plantation houses in the American colonies.

Domed and colonnaded Chiswick House, designed by the architect Earl of Burlington in 1729, is much more purely Palladian – a Roman-style temple for the art collections it was built to display.

CHANGING FASHIONS

Chiswick’s sumptuous interiors are by William Kent. Those of Kenwood House, Lord Mansfield’s Hampstead villa (1764–79 and later), were created by the still more famous Robert Adam. Both make extensive use of bright colours – Georgian interior design was not all pastel shades and chaste simplicity.

There was in fact no single Georgian interior style. Earlier Classicism gave way, by the 1760s, to ‘Frenchified and effeminate’ Rococo, or Chinoiserie, or both combined. House owners who dared to be different might choose the mock-medieval Gothick pioneered at Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, Twickenham (1747), or ‘Egyptian’ or ‘Grecian’ modes.

By the early 19th century, austere Classicism no longer prevailed. A great array of styles was in evidence, from the severely simple Greek Revival exemplified by Belsay Hall, Northumberland, and The Grange at Northington, Hampshire, to the Indian-Chinese-Egyptian Brighton Pavilion, designed by the Prince Regent’s favourite architect, John Nash.

TOWNS AND TERRACES

The most astonishingly grandiose surviving interiors of the period are those of Apsley House, a Robert Adam creation remodelled on an imperial scale for the Duke of Wellington between 1819 and 1830.

Apsley is also the last unaltered survivor of the great London town houses, indispensable to any Georgian family with pretensions to power or social leadership. From 1811, those of lesser means could choose instead a house in one of the new, palatial-looking Regent’s Park terraces – in fact ordinary brick dwellings behind showy stuccoed façades – designed by Nash.

From Wakefield to Weymouth, terraces and squares of more modest but delightful town houses are among the Georgian period’s most important architectural legacies.

Many of the same towns also retain imposing public buildings of the period, which reflected growing commercial success and civic pride. Town halls, theatres, concert halls, exchanges and shopping emporia sprung up, and fashionable spas and resorts like Bath and Brighton flourished.

CHURCHES OR TEMPLES?

Gothic Revivalist Victorians regarded Classical Georgian churches as too reminiscent of paganism. Nicholas Hawksmoor’s massive and individualistic Christ Church, Spitalfields (1716–31), does indeed recall Imperial Rome, while James Gibbs’s St Martin-in-the Fields (1722–6) could be a Greek temple, but for its spire.

More typical of the period, though, are remote country churches like Hannah-cum-Hagnaby in Lincolnshire, or the charming St Mary’s near Whitby Abbey, North Yorkshire, jam-packed with box pews and galleries and dominated by its towering pulpit.

Such ‘prayer-book’ churches – rare survivors of Victorian church restoration – were designed for congregational worship, shifting the focus away from the altar. They bear a close resemblance to English Heritage’s only Nonconformist place of worship, Goodshaw Chapel, Lancashire (1760–1809).

More about Georgian England

-

Georgians: Parks and Gardens

The growing fashion for scenery in the Georgian period, accompanied by theories on nature, led to more naturalistic landscape designs that were an early expression of Romanticism.

-

Georgians: Power and Politics

Until the very end of the Georgian period, power belonged almost exclusively to those who owned substantial land or wealth.

-

Georgians: Architecture

The classic Georgian building is the Classical country house. But this is also the period that saw the first steps towards a coherent approach to town planning.

-

Georgians: War

For much of the Georgian period Britain was at war – usually with France. Many of these conflicts were played out on a world stage, to defend or expand the burgeoning British Empire.

Georgian Stories

-

Capability Brown at Audley End

How a contract in 1763 between England’s foremost landscape gardener and a landowner with a military past deteriorated into a furious exchange of letters.

-

Black Prisoners at Portchester Castle

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793, the islands of the Caribbean were drawn into the conflict. In 1796 free black soldiers were captured and sent to Portchester as prisoners of war.

-

Romantic Female Friendship

In the 18th century, among fashionable women, a cult of same-sex ‘romantic friendship’ was accepted, even if to some contemporary observers it appeared ‘queer’

-

The Invention of the Wellington Boot

How the Duke of Wellington, victor at the Battle of Waterloo and fashion icon, gave his name to the humble welly.

-

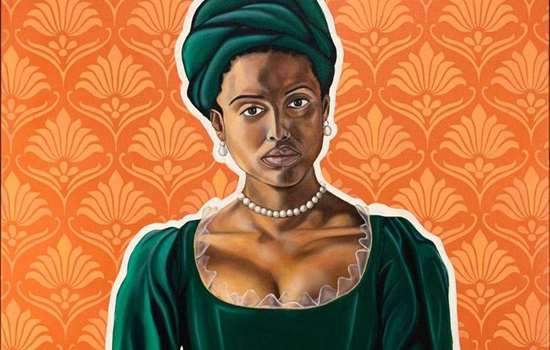

Dido Belle

A mixed-race woman, Dido Belle was raised as part of an aristocratic family in Georgian Britain at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.

-

Philip Thicknesse, Landguard's Loosest Cannon

How Philip Thicknesse finally got his comeuppance after a madcap life of self-inflicted scandal in 18th-century England.

-

The Only People Ever Killed at Tilbury Fort

The only fatalities ever reported at Tilbury Fort were thanks to a game of cricket in 1776. Or is this extraordinary story just a tall tale?

-

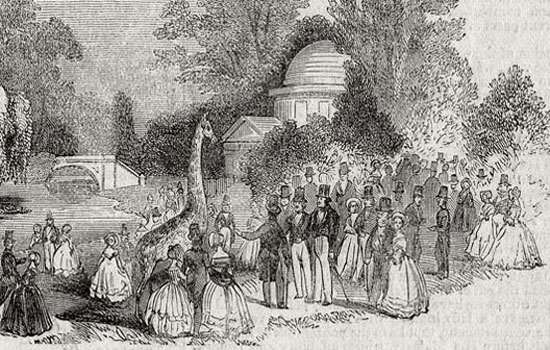

An Emperor and an Aristocrat's Menagerie

How the 19th-century menagerie at Chiswick House in west London was part of a wider tradition of keeping exotic creatures on aristocratic estates.