Georgians: War

For much of the Georgian period Britain was at war – usually with France. Many of these conflicts were played out on a world stage, to defend or expand the burgeoning British Empire.

WORLD WARS

The Seven Years War (1756–63) secured Canada and (eventually) India for Britain. But during the American War of Independence (1775–83), French, Spanish and Dutch support for the revolutionary colonists contributed to Britain’s defeat, and the loss one of its most important imperial assets.

The professional army of Britain was small compared to those of its neighbours. For wars on land, Britain drew on its growing wealth to subsidise its allies.

THE ROYAL NAVY

But Britain depended above all on the Royal Navy, which was the best in the world by the later 18th century. Its officers, nearly all trained at sea from boyhood, formed a close-knit professional caste – Lord Nelson’s ‘band of brothers’.

Roughly half of its seamen, mainly English and Irish, were quasi-legally conscripted by ‘press gangs’. Given the appalling conditions they endured at sea, it is remarkable that serious mutinies were rare, and that the navy was so outstandingly successful.

It guarded Britain’s shores from foreign enemies, but equally if not more important was its role in protecting Britain’s colonies and trade routes. Commerce was, after all, the main source of the country’s wealth and power.

INVASION SCARES

The only genuine invasions of England during the Georgian era came by land. Periodic Jacobite revolts against the house of Hanover and the Act of Union sought to return the Stuarts to the throne. In 1715 a rain-soaked rebel ‘army’ quickly surrendered at Preston in Lancashire, but in 1745 Prince Charles Edward Stuart posed a rather more serious threat, invading Cumbria from Scotland with over 5,000 men.

The ramshackle local militia garrison of Carlisle Castle capitulated without a fight, and the Jacobites pressed on to Derby. Soon, though, they were back in Carlisle, having failed to win English support – before retreating to Scotland with three government armies on their heels. Charles and his army were heavily defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. Charles escaped to the Continent and continued to plot, but the Jacobite cause withered away.

Later on in the period, invasion from France posed a greater threat. In 1803 it was believed that Napoleon’s 90,000-strong army was poised to cross the Channel in a single night in flat-bottomed rowing barges. Although the navy had complete control of the Channel, English patriots still watched their warning beacons anxiously.

DEFENCES

To bolster England’s defences, the government strengthened Dover Castle – constructing an underground barracks for 2,000 soldiers – and on the nearby Western Heights raised the largest English fortifications of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815).

In 1808, when the invasion threat had almost vanished, the government began building a chain of 103 single-cannon ‘Martello towers’ (including Dymchurch Martello Tower, Kent) to guard the cliffless Sussex and Kent coast between Eastbourne and Folkestone. In 1812 this chain of defences was extended into Essex and Suffolk.

VICTORY

By this time the anti-French forces were turning the tide against Napoleon, whose army and reputation had suffered heavy losses during the retreat from Russia in 1812.

Britain and its allies invaded France in March 1814, forcing Napoleon’s abdication and exile to Elba. His escape 11 months later and return to Paris led to a renewal of the war. Eventually, on 18 June 1815 – with substantial German, Belgian and Dutch assistance – Wellington defeated the emperor at Waterloo.

Remembered at English Heritage’s Apsley House and Wellington Arch in London and Walmer Castle, Kent, the ‘Iron Duke’ was celebrated as the great military hero of Europe as the Georgian period drew to a close.

More about Georgian England

-

Georgians: Parks and Gardens

The growing fashion for scenery in the Georgian period, accompanied by theories on nature, led to more naturalistic landscape designs that were an early expression of Romanticism.

-

Georgians: Power and Politics

Until the very end of the Georgian period, power belonged almost exclusively to those who owned substantial land or wealth.

-

Georgians: Architecture

The classic Georgian building is the Classical country house. But this is also the period that saw the first steps towards a coherent approach to town planning.

-

Georgians: War

For much of the Georgian period Britain was at war – usually with France. Many of these conflicts were played out on a world stage, to defend or expand the burgeoning British Empire.

Georgian Stories

-

Capability Brown at Audley End

How a contract in 1763 between England’s foremost landscape gardener and a landowner with a military past deteriorated into a furious exchange of letters.

-

Black Prisoners at Portchester Castle

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793, the islands of the Caribbean were drawn into the conflict. In 1796 free black soldiers were captured and sent to Portchester as prisoners of war.

-

Romantic Female Friendship

In the 18th century, among fashionable women, a cult of same-sex ‘romantic friendship’ was accepted, even if to some contemporary observers it appeared ‘queer’

-

The Invention of the Wellington Boot

How the Duke of Wellington, victor at the Battle of Waterloo and fashion icon, gave his name to the humble welly.

-

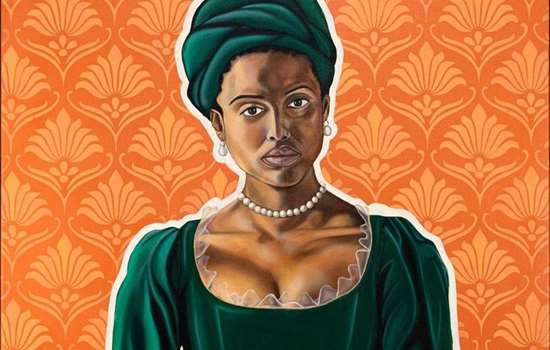

Dido Belle

A mixed-race woman, Dido Belle was raised as part of an aristocratic family in Georgian Britain at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.

-

Philip Thicknesse, Landguard's Loosest Cannon

How Philip Thicknesse finally got his comeuppance after a madcap life of self-inflicted scandal in 18th-century England.

-

The Only People Ever Killed at Tilbury Fort

The only fatalities ever reported at Tilbury Fort were thanks to a game of cricket in 1776. Or is this extraordinary story just a tall tale?

-

An Emperor and an Aristocrat's Menagerie

How the 19th-century menagerie at Chiswick House in west London was part of a wider tradition of keeping exotic creatures on aristocratic estates.