BRITAIN AND ENGLAND

The union of the kingdoms of England and Scotland in 1707 created Great Britain. A new British identity was celebrated by the anthem Rule Britannia (1740), the foundation of the British Museum (1753), and the publication of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1768).

But England retained its own distinctive character during the early Georgian period. Its refined manners and fashions and its classically influenced art, literature and architecture, were juxtaposed by casual brutality, violent sports, squalor and epidemic gin drinking. Handel’s oratorios flourished alongside the debauchery depicted by his friend William Hogarth.

HANOVERIANS AND JACOBITES

The property-owning elite controlled politics. But when Queen Anne died in 1714 with no surviving children, not everyone was pleased with the elite’s choice of monarchy. The German Hanoverians, who were distant Protestant relations of the exiled Stuarts, were brought in to succeed Anne. George I (r.1714–27), who scarcely spoke English, faced an almost immediate rebellion (1715–16) from the Jacobites, who supported the restoration of the Stuarts.

The more serious Scots Jacobite invasion of 1745, which had strong support in north-west England, reached Derby, but succeeded only in rallying widespread English support for George II (r.1727–60), and inspiring God Save the King, the world’s first national anthem.

The Battle of Culloden (1746) finally extinguished the Jacobite threat, freeing British forces and their allies to wrest Canada and India from France during the Seven Years War (1756–63). Captain James Cook claimed Australia for Britain in 1770.

Although America was lost after the bitter Revolutionary War of 1775–83, an expanding empire provided Britain with a source of raw materials and new markets for its manufactured goods.

Much of Britain’s affluence was underpinned by the Atlantic slave trade. Despite growing domestic disapproval, the trade was only abolished in 1807, and slavery itself was not made illegal until 1834.

‘FARMER GEORGE’

George III (r.1760–1820), the first Hanoverian king born in England, was affectionately nicknamed ‘Farmer George’ because of his interest in agriculture. Many of his richer rural subjects were busily (and profitably) improving farming methods. Meanwhile, smallholders and customary tenants were impoverished by the enclosure of land and the commercialisation of agriculture.

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The lives of many more, especially in the north and midlands, were transformed by the rapid progress after 1770 of the Industrial Revolution. England was turned into the ‘workshop of the world’ by new technologies like steam power, improved transport networks and enterprising men like the iron-founding Darbys of Iron Bridge, the pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, and the cotton mill owner Richard Arkwright.

Key to the success of many industries were the new manufactories – or factories – operated by hordes of ill-paid workers, including many women and children. The growth of populations in industrial areas attracted the the Methodist preacher John Wesley, whose evangelical take on Christianity had broader appeal than the established Church of England.

Regency and Heroes

From 1788 George III’s intermittent mental illness raised the prospect of the regency of his son George. In his youth he’d been celebrated as the ‘First Gentleman of Europe’, in corpulent later life derided as the ‘Prince of Whales’. Though his formal rule as Prince Regent lasted only from 1811 until his own accession as George IV in 1820, the entire late Georgian period is often labelled Regency.

Defined for many by the novels of Jane Austen, the Regency period also gave birth to the works of Romantic poets like William Wordsworth and John Keats, the elegance of Beau Brummel’s fashions and John Nash’s London terraces, and the gradual replacement of the robustly corrupt culture of the early Georgian period with a new ‘high moral seriousness’.

In the background was the long conflict (1793–1815) with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. Nelson’s naval triumphs at the Nile (1797) and Trafalgar (1805) did not stop invasion scares in 1798 and 1803, and only in 1809 did the Duke of Wellington’s successes against the French in Spain begin to make equivalent victory on terra firma look possible.

The final victory of Britain and her allies at Waterloo in 1815 confirmed her status as the dominant European power.

LIMITED REFORM AND A NEW AGE

The demands of war further increased the pace of the Industrial Revolution. The slump that followed peace, however, resulted in political and social unrest, ruthlessly suppressed after the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, when cavalry charged a peaceful crowd gathered to demand parliamentary reform. Although the limited political concessions of the Great Reform Act of 1832 averted further troubles, it still allowed only about one in six Englishmen to vote.

By now the world’s first passenger train had run (in 1825) on the Stockton and Darlington Railway, and the first inter-city railway powered exclusively by steam engines had opened (in 1830). This was just one symbol of the new age that was arriving for Britain and the world, as William IV (r.1830–37) was succeeded by his far more formidable niece, Victoria, in 1837.

Georgian Stories

-

Capability Brown at Audley End

How a contract in 1763 between England’s foremost landscape gardener and a landowner with a military past deteriorated into a furious exchange of letters.

-

Black Prisoners at Portchester Castle

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793, the islands of the Caribbean were drawn into the conflict. In 1796 free black soldiers were captured and sent to Portchester as prisoners of war.

-

Romantic Female Friendship

In the 18th century, among fashionable women, a cult of same-sex ‘romantic friendship’ was accepted, even if to some contemporary observers it appeared ‘queer’

-

The Invention of the Wellington Boot

How the Duke of Wellington, victor at the Battle of Waterloo and fashion icon, gave his name to the humble welly.

-

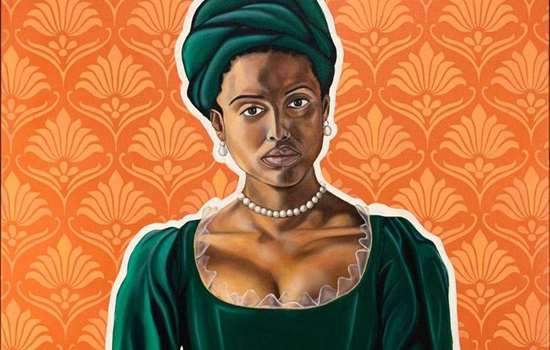

Dido Belle

A mixed-race woman, Dido Belle was raised as part of an aristocratic family in Georgian Britain at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.

-

Philip Thicknesse, Landguard's Loosest Cannon

How Philip Thicknesse finally got his comeuppance after a madcap life of self-inflicted scandal in 18th-century England.

-

The Only People Ever Killed at Tilbury Fort

The only fatalities ever reported at Tilbury Fort were thanks to a game of cricket in 1776. Or is this extraordinary story just a tall tale?

-

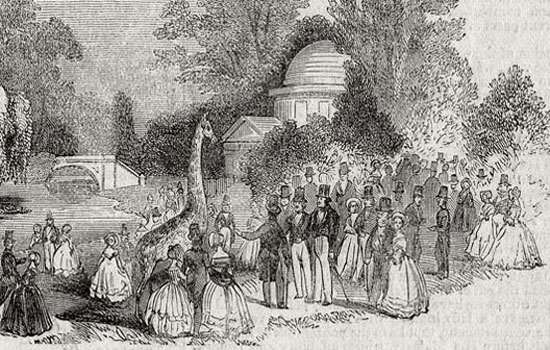

An Emperor and an Aristocrat's Menagerie

How the 19th-century menagerie at Chiswick House in west London was part of a wider tradition of keeping exotic creatures on aristocratic estates.

More about Georgian England

-

Georgians: Parks and Gardens

The growing fashion for scenery in the Georgian period, accompanied by theories on nature, led to more naturalistic landscape designs that were an early expression of Romanticism.

-

Georgians: Power and Politics

Until the very end of the Georgian period, power belonged almost exclusively to those who owned substantial land or wealth.

-

Georgians: Architecture

The classic Georgian building is the Classical country house. But this is also the period that saw the first steps towards a coherent approach to town planning.

-

Georgians: War

For much of the Georgian period Britain was at war – usually with France. Many of these conflicts were played out on a world stage, to defend or expand the burgeoning British Empire.