Georgians: Parks and Gardens

At the start of the Georgian period, parks and gardens had formal layouts with well-defined axes and avenues. But the growing fashion for scenery, accompanied by theories on nature and on how painterly principles might be used, led to more naturalistic designs that were an early expression of the Romantic movement. Towards the end of the period, picturesque theory sanctioned the return of formality to the garden.

THE PLEASURE GARDEN

From the 1710s the highly ornamented country house garden was simplified and made grander, as parterres became plain grass and perimeter walls came down for a more panoramic view.

On the other hand, surrounding plantations were appropriated or planted, and given meandering paths connecting openings decorated with temples, statues, rustic ruins, eyecatchers and water features. These were often surrounded by terraces and ha-has. In smaller suburban gardens Alexander Pope’s catchphrase ‘surprise, vary and conceal the bounds’ was more appropriate.

Charles Bridgeman was the leading practitioner in the 1720s and helped Alexander Pope to create the gardens at Marble Hill, west London. In the parks he worked on, Bridgeman married loose formal designs to the landscape by creating plantations, lakes, broad vistas and carriage rides. Stephen Switzer and Batty Langley (who worked at Wrest Park, Bedfordshire) wrote books promoting these trends, but were not such prolific designers.

NATURE

From the 1730s the term ‘rural’ was applied to irregular planting, bodies of water and garden architecture. William Kent brought these elements together in his designs, at first for the settings for his garden buildings, and then for larger areas set out ‘without line or level’.

Chiswick House in west London was probably the first place in England where Kent put these new ideas into practice. This new naturalistic look typically had artificial water in valleys, while the folds in the landscape were draped with groves, and knolls were heightened with clumps.

These landscapes imaginatively recreated scenery from classical Arcadia and Elysium, and temples and grottoes enhanced the illusion and mood. Variations drew on Chinese, Gothick or rustic architecture. Supporters of this style, like Horace Walpole, emphasised the use of landscape painting principles to ‘perfect’ Nature. Parallels were also drawn between the free expression in the designs was and the freedom of the English from autocratic rule.

THE LANDSCAPE PARK

Large parks had been created since the start of the century, and having been ornamentally designed from the 1730s, were gradually transformed into artificial but naturalistic landscapes.

The chief practitioner from the 1750s was Capability Brown. Over the next generation he and his followers made hundreds of ‘landscape parks’, including those at Audley End, Essex, and Wrest Park. The larger ones generally contained deer, as at Auckland Castle, Durham (with its Gothic Revival Deer House), but many smaller ones were grazed by cattle and sheep. Ruins, such as Roche Abbey, South Yorkshire, and Old Wardour Castle, Wiltshire, were often incorporated into such landscapes. England is sometimes said to have been the first among many European countries to embrace Romanticism in landscape design.

GAME AND THE KEEPER

Parks provided privacy, and road diversions could be arranged between members of the county elite. Landowners became obsessed with sport, particularly fox-hunting and shooting game birds, and game laws imposed heavy penalties on poachers.

Beyond the boundaries of parks, ‘improvements’ included the enclosure of common land in various parts of the country, which was at its height from 1760 to 1820. Walls were built and hedges were planted dividing the land into rectangular fields. The old model of the English landscape, with ordered parks and unordered countryside, was turned on its head.

Although the population of the countryside rose, there was a drift to the new industries in cities and industrial areas.

THE PICTURESQUE DEBATE

In the 1790s Humphry Repton adopted the mantle of Capability Brown and prepared ‘red books’ illustrating proposals for scores of parks: the designed landscape at Kenwood, London, was largely his creation. He was challenged by Uvedale Price and others who advocated treating a landscape like a landscape painting, with rough texture and rocky outcrops seen through a frame in the foreground. Sir Charles Monck’s quarry garden at Belsay, Northumberland, is one of the most remarkable examples of the Picturesque style in England.

Meanwhile Brown’s gentle sweeps and curves became the target of virulent criticism. This ‘picturesque debate’ took place against the backdrop of an England that had become the greatest industrial and military power in the world.

Population increases and the Napoleonic Wars resulted in high food prices and the rise of larger farms. Many of the brick buildings in the countryside today date from this heyday of 1780 to 1815, and agriculture was intensified by land reclamation from the Fens and from moorland.

REGENCY TASTE

Formal gardens were back in fashion the 1810s, and garden building trends became eclectic, with Indian, Italian and French styles all being explored. Technical improvements, like those in conservatory design, kept pace with the achievements of science and industrialisation – a pattern exemplified by the heated wall and hothouses at Belsay.

The disposable wealth of agricultural landowners declined as prices came down, and because of ‘strict settlements’ of land to protect family fortunes. Few new parks were created after 1820. By contrast, the expanding and prosperous mercantile classes wanted suburban villas and gardens, and these became the most numerous clients of the elderly Humphry Repton and the young John Claudius Loudon.

More about Georgian England

-

Georgians: Parks and Gardens

The growing fashion for scenery in the Georgian period, accompanied by theories on nature, led to more naturalistic landscape designs that were an early expression of Romanticism.

-

Georgians: Power and Politics

Until the very end of the Georgian period, power belonged almost exclusively to those who owned substantial land or wealth.

-

Georgians: Architecture

The classic Georgian building is the Classical country house. But this is also the period that saw the first steps towards a coherent approach to town planning.

-

Georgians: War

For much of the Georgian period Britain was at war – usually with France. Many of these conflicts were played out on a world stage, to defend or expand the burgeoning British Empire.

Georgian Stories

-

Capability Brown at Audley End

How a contract in 1763 between England’s foremost landscape gardener and a landowner with a military past deteriorated into a furious exchange of letters.

-

Black Prisoners at Portchester Castle

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793, the islands of the Caribbean were drawn into the conflict. In 1796 free black soldiers were captured and sent to Portchester as prisoners of war.

-

Romantic Female Friendship

In the 18th century, among fashionable women, a cult of same-sex ‘romantic friendship’ was accepted, even if to some contemporary observers it appeared ‘queer’

-

The Invention of the Wellington Boot

How the Duke of Wellington, victor at the Battle of Waterloo and fashion icon, gave his name to the humble welly.

-

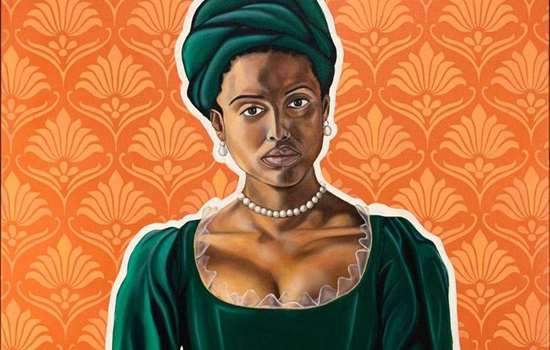

Dido Belle

A mixed-race woman, Dido Belle was raised as part of an aristocratic family in Georgian Britain at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.

-

Philip Thicknesse, Landguard's Loosest Cannon

How Philip Thicknesse finally got his comeuppance after a madcap life of self-inflicted scandal in 18th-century England.

-

The Only People Ever Killed at Tilbury Fort

The only fatalities ever reported at Tilbury Fort were thanks to a game of cricket in 1776. Or is this extraordinary story just a tall tale?

-

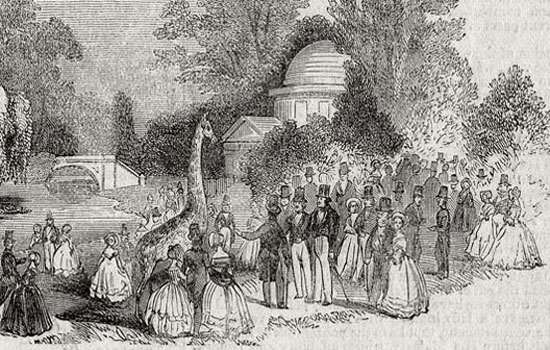

An Emperor and an Aristocrat's Menagerie

How the 19th-century menagerie at Chiswick House in west London was part of a wider tradition of keeping exotic creatures on aristocratic estates.