Georgians: Power and Politics

Until the very end of the Georgian period, power belonged almost exclusively to those who owned substantial land or wealth: the aristocracy, and the mercantile and banking elites who bought their way into the ruling circle.

MONARCH AND PARLIAMENT

The 18th century was a period of political stability. The Crown depended heavily on Parliament, resulting in a limited monarchy that proved stable and effective. The principle that Parliament would sit every year, and that the government needed to command a majority in the House of Commons, emerged in this period.

Robert Walpole, who dominated politics during the reigns of the first two Georges, is regarded as Britain’s first prime minister. In 1735 George II gave him 10 Downing Street as a residence.

LANDED INTEREST

Members of the ruling elite were interconnected by marriages which maintained or increased their great landed estates. They met regularly at town or country mansions – such as Apsley House, Audley End, Chiswick House, Kenwood and Wrest Park – or at fashionable resorts like Bath. These grandees, usually members of the Whig Party, exercised enormous influence through their connections and patronage.

The Tory Party drew its strength mainly from the rural gentry, rather than the aristocracy. Whigs and Tories vied with each other for control of Parliament, but whichever faction was in the ascendant, only about 200,000 property-owning men (and no women) had the right to vote them in – or out – of power.

BRIBERY AND CORRUPTION

This electorate expected to be bribed. The going rate for even a ‘cheap’ constituency was £5 a vote, plus copious food and (especially) drink. The politician-playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s expenses for election in Stafford in 1780 were over £1,000.

At least in Stafford the electors had some say in whom they voted for. Many other constituencies were ‘pocket boroughs’, owned outright by a major landowner. In such cases, the entire electorate were the landowner’s tenants, obliged to vote (in a public ballot) as directed or face eviction. In the 1760s, 205 of the 406 English constituencies were controlled by just 111 aristocratic owners.

If not wanted for a relative, seats could be sold to the highest acceptable bidder. A single nomination could cost £9,000; the permanent purchase of a constituency, and with it the ongoing right to nominate its two MPs, cost much more. In 1802 Old Sarum in Wiltshire reputedly changed hands for £60,000.

Old Sarum was the most notorious of the 56 so-called ‘rotten boroughs’, places whose right to return MPs extended back to the Middle Ages, but which were almost completely depopulated by Georgian times.

Meanwhile the people of the rapidly expanding new towns, such as Manchester, had no direct parliamentary representation at all.

REFORM

Influential figures long accepted this system, partly because they themselves relied upon aristocratic patronage. Growing agitation for reform was hampered by the French Revolution and the subsequent wars with France (1793–1815). Critics were marginalised or silenced, and regarded as at best unpatriotic, at worst dangerous revolutionaries.

A slender majority of the political establishment, however, recognised that some degree of change was required to stave off revolution.

In 1832, after two years of parliamentary manoeuvring and opposition from the Duke of Wellington and the House of Lords, the first Reform Act for England and Wales was passed. This abolished rotten and pocket boroughs and created 135 new seats, giving 41 of the larger English towns their first MPs.

The electorate was increased from about 400,000 to 650,000, about one in six of the adult male population. Yet the beneficiaries were the richer middle classes, rather than the great majority of working people. The ruling elite had expanded, but an elite still ruled.

More about Georgian England

-

Georgians: Parks and Gardens

The growing fashion for scenery in the Georgian period, accompanied by theories on nature, led to more naturalistic landscape designs that were an early expression of Romanticism.

-

Georgians: Power and Politics

Until the very end of the Georgian period, power belonged almost exclusively to those who owned substantial land or wealth.

-

Georgians: Architecture

The classic Georgian building is the Classical country house. But this is also the period that saw the first steps towards a coherent approach to town planning.

-

Georgians: War

For much of the Georgian period Britain was at war – usually with France. Many of these conflicts were played out on a world stage, to defend or expand the burgeoning British Empire.

Georgian Stories

-

Capability Brown at Audley End

How a contract in 1763 between England’s foremost landscape gardener and a landowner with a military past deteriorated into a furious exchange of letters.

-

Black Prisoners at Portchester Castle

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793, the islands of the Caribbean were drawn into the conflict. In 1796 free black soldiers were captured and sent to Portchester as prisoners of war.

-

Romantic Female Friendship

In the 18th century, among fashionable women, a cult of same-sex ‘romantic friendship’ was accepted, even if to some contemporary observers it appeared ‘queer’

-

The Invention of the Wellington Boot

How the Duke of Wellington, victor at the Battle of Waterloo and fashion icon, gave his name to the humble welly.

-

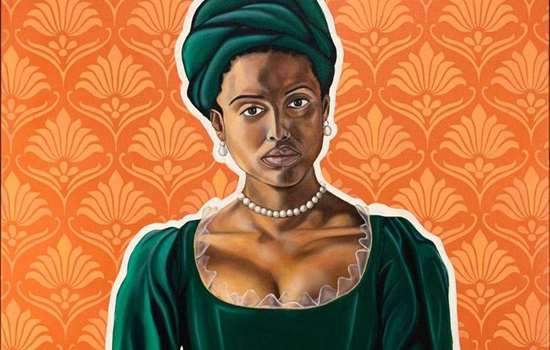

Dido Belle

A mixed-race woman, Dido Belle was raised as part of an aristocratic family in Georgian Britain at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.

-

Philip Thicknesse, Landguard's Loosest Cannon

How Philip Thicknesse finally got his comeuppance after a madcap life of self-inflicted scandal in 18th-century England.

-

The Only People Ever Killed at Tilbury Fort

The only fatalities ever reported at Tilbury Fort were thanks to a game of cricket in 1776. Or is this extraordinary story just a tall tale?

-

An Emperor and an Aristocrat's Menagerie

How the 19th-century menagerie at Chiswick House in west London was part of a wider tradition of keeping exotic creatures on aristocratic estates.