Prehistory: Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as architecture. But these buildings still inspire awe today, whether through the mysteries of their meaning, the intricacy or scale of their design, or the ingenuity of their construction.

DESIGN AND ENGINEERING

The oldest surviving designed structures in Britain are the stone chambered tombs that form part of long barrows, raised between about 3800 and 3400 BC during the early Neolithic period. The earliest of all are perhaps the Medway Megaliths, a group of monuments in Kent that includes Kit's Coty House.

Others, such as the long barrows at Belas Knap, Nympsfield and Uley, are part of the widespread ‘Cotswold–Severn’ group, and share a remarkable family resemblance. They’re all trapezoidal mounds that cover burial chambers built of massive boulders and sections of dry-stone walling. They have forecourts for ceremonies at the wider end.

Some burial chambers have been exposed when their mounds have eroded, like Trethevy Quoit, Cornwall. They brilliantly showcase the engineering skills required to construct prehistoric stone monuments.

STONE AND TIMBER CIRCLES

Stone circle design varies considerably. The King’s Men circle at Rollright Stones, Oxfordshire, was seemingly once a continuous ring-wall of stones, with a single narrow entrance; and there is debate about whether the recumbent stones at Arbor Low in Derbyshire ever stood upright.

Sometimes stones were selected for their natural shape. At West Kennet Avenue in Wiltshire they are set in pairs, with a squat diamond-shaped stone matched with a slender straight-sided one.

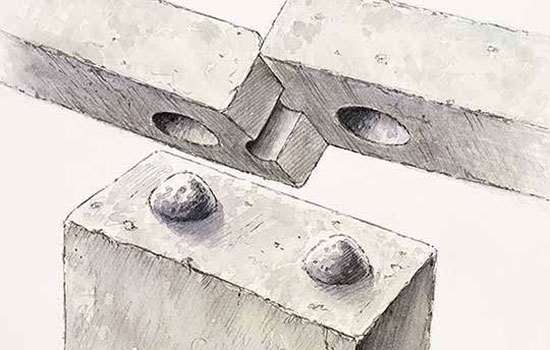

The builders of Stonehenge uniquely went one step further: it is the only known stone circle with horizontal lintels. Here the sarsen stones were laboriously shaped to create regular rectangular blocks, with smooth surfaces. Raising the stones upright and setting the lintels in place rank among the most impressive of all prehistoric engineering feats.

Timber post circles were built during the same period as stone circles. Examples include Woodhenge and the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls. One of the most enigmatic was ‘Seahenge’ in Norfolk, which had an upturned tree stump at its centre.

Some stone monuments are known to have had substantial timber components. The Sanctuary, near Avebury, had six concentric timber circles and two of stone.

HOUSES

Houses are almost invisible in the archaeological record of the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Rare examples include some early Neolithic rectangular buildings discovered not far from Arthur's Stone, Herefordshire, and late Neolithic small square houses at Durrington Walls.

We don’t know the reason for this lack of evidence. It could be that houses were built of timber, which has long since rotted away, or people may not have had settled lifestyles.

The first round houses were built in the Bronze Age, and are commonly found at middle Bronze Age to late Iron Age settlements, such as Maiden Castle, Dorset, Grimspound, Devon, and Silchester, Hampshire. Some are substantial circular timber buildings, with floor areas exceeding 100 square metres.

In Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, a local type of stone-built ‘courtyard house’ was constructed from the late Iron Age and into the Romano-Cornish period. There are examples at Carn Euny, Chysauster and Halangy Down.

REGIONAL MONUMENTS

Some types of monument are found only in certain parts of western England. Neolithic or early Bronze Age Scillionian entrance graves, which usually have an entrance passage leading to a burial chamber, are found solely in west Cornwall and on the Isles of Scilly, as at Porth Hellick on St Mary’s and Ballowall on the mainland.

Also unique to the far west of Cornwall, and usually found as part of Iron Age or Romano-Cornish settlements, are fogous – complexes of underground passages built with massive stone slabs. You can see fogous at Carn Euny and Halliggye.

EARTHWORKS

In the earlier Neolithic period, huge monuments were created simply by digging and moving earth to create banks and ditches. Causewayed enclosures, such as Windmill Hill, Wiltshire, had circuits of concentric ditches. Cursus monuments, like the mile-long one near Stonehenge, dramatically changed the appearance of the landscape.

In the late Bronze Age and Iron Age, most settlements were only lightly defended. In many parts of southern and western England, their occupants may have retreated in times of trouble to hillforts.

Their earthen ramparts were often originally faced and reinforced with dry-stone walling or timber. Sarsen stones were used at Uffington Castle. The builders of hillforts designed them to repel attackers, using overlapping or inturned ramparts (as at Old Oswestry, Shropshire), and separate ‘hornworks’ outside entrances. At Maiden Castle, Dorset, several of these devices were combined. They stopped attackers being able to run straight at entrances, and funnelled them into specific densible areas.

More about Prehistoric England

-

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.