Prehistory: Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived. The advent of farming in about 4000 BC brought with it the earliest surviving traded goods: stone-headed axes.

Trading in Symbols

Though axes were vital for the practical work of clearing land and woodworking, some had greater symbolic significance - and presumably greater value. Over 100 axe-heads made from polished jade quarried high in the Italian Alps have been found in Britain. Most were never used and many were deposited as votive offerings.

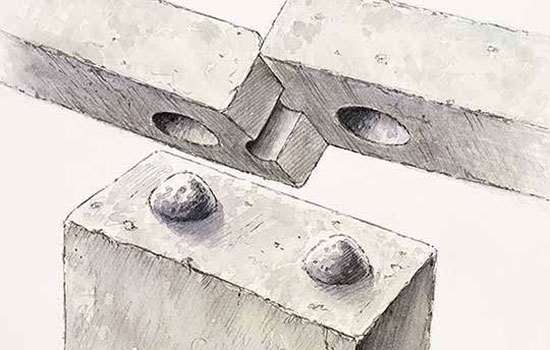

Axe-heads from British ‘axe factories’ were more numerous and widely traded, such as those from Langdale in the Lake District. Stone there was deliberately mined from the most dangerous and inaccessible cliffs of the quarry.

FLINT MINING

A greenstone axe-head from Cornwall was among the offerings found at Grime's Graves, far away in eastern England. There, some 4,000 tons of flint were mined between 2600 and 1500 BC, from pits sunk up to 13 metres deep through chalk, to reach the high-quality black flint ‘floorstone’. Usable flint was more readily available on the surface, but tools made from mined flint appear to have had a special significance.

At Grime's Graves and Langdale stone tools left the site as ‘rough-outs’ that would be polished elsewhere. How, where and what the finished products were traded for is uncertain. But axe-heads are frequently found at Neolithic causewayed enclosure meeting places like Windmill Hill, which were the sites of large-scale feasting for the living and ceremonies for the dead. They have also been found at at Castlerigg Stone Circle, which might have been a significant stop on a trading route.

METALWORKING

Stone tools gradually lost their importance after the arrival of bronze-working technology in Britain in about 2300 BC – long after it was available elsewhere in Europe. Bronze’s raw materials, copper and tin, existed abundantly here, but their exploitation developed over time.

Copper and tin ingots found in the sea off Salcombe in Devon, apparently from a ship wrecked in about 900 BC, were probably travelling into Britain, rather than out of it. Though there are hints from sites like Carn Euny, prehistoric evidence for Cornish tin mining is scanty. But finds of moulds, crucibles and socketed axes at Beeston Castle in Cheshire, dating from about this time, show that native bronzesmiths were working local copper ores.

Metalworking in Britain reached its peak in the Early Bronze Age, when fine gold, copper and bronze jewellery and weapons were buried with the dead under round barrows, such as those at Winterbourne, Dorset.

INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Imported exotic goods – including amber from the Baltic and gold from Ireland – have also been discovered in Bronze Age round barrows, suggesting that there were established European trading networks. By the later Iron Age, southern England’s principal trading partners were northern Gaul (France) and Armorica (Brittany).

Hengistbury Head in Dorset became a thriving port, probably exchanging locally-smelted iron for goods such as figs, glass, tools, pottery and above all jars of wine, imported either via Brittany or directly from Italy.

COINAGE

Excavations at Hengistbury have also produced evidence of a concept that was entirely new to Britain: coinage. Coins were probably minted there for the local Durotriges tribe. At first, British coins imitated Gaulish originals, as did the silver and gold coinage produced from about 40 BC for rulers throughout southern and eastern England, often inscribed with their names.

An extraordinary hoard of some 5,000 coins of the local Corieltauvi tribe was found in 2000 near Hallaton in Leicestershire. With them were found Roman luxury items, also a dominant feature of the grave goods buried with a British king in Lexden tumulus in Essex. The findings show that Britain was becoming a part of the imperial trade network even before the Roman conquest of AD 43.

More about Prehistoric England

-

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.