READ MORE ABOUT ROMAN BRITAIN

-

EXPLORE ROMAN BRITAIN

Browse our articles on the Romans to discover the impact and legacy of the Roman era on Britain’s landscape, buildings, life and culture.

-

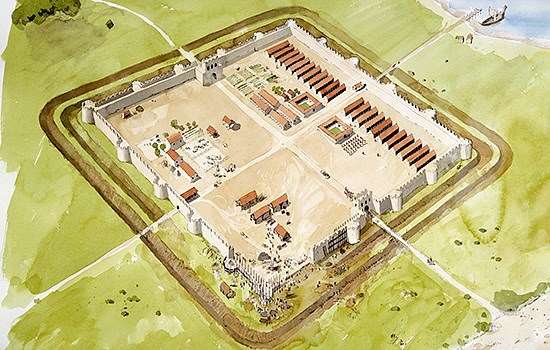

THE ROMAN INVASION OF BRITAIN

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

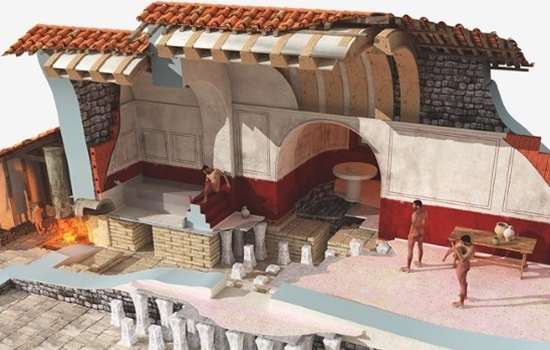

ROMAN BATHING

Bathing was central to Roman life. Discover what Roman bath-houses can tell us about the culture and people of Roman Britain.

-

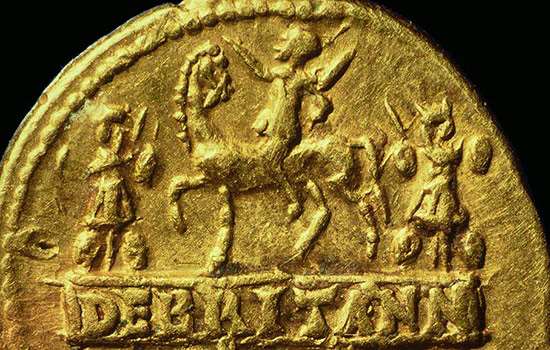

GATEWAY TO BRITANNIA: RICHBOROUGH’S ARCH

The story of Richborough’s monumental arch reveals the great importance of Richborough to the Romans as the gateway to Britannia.