Architecture

While the Elizabethans built great country houses, some courtiers of the Jacobean period (the reign of James I) raised even bigger ones, with yet more elaborate ornament. Later in the century, Sir Christopher Wren’s new churches rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

JACOBEAN EXTRAVAGANCE

When it was rebuilt in 1603–14, the ‘Palace of Audley End’ in Essex was the largest private house in England. It was even bigger and grander than most royal residences. James I quipped that it was ‘too big for a king’.

Such vast mansions could ruin their builders. The Devon squire Edward Seymour spent £20,000 on Berry Pomeroy Castle, before abruptly running out of cash and leaving his extensions unfinished.

Just as elaborate, the battlemented and pinnacled ‘Little Castle’ at Bolsover in Derbyshire (1620s), with its exquisitely decorated interiors, was an exercise in pure fantasy.

Jacobean extravagance also appeared in more modest dwellings. At Great Yarmouth Row Houses in Norfolk and Bessie Surtees House, Newcastle, merchants’ town houses were embellished with elaborate plaster ceilings. Much of this decoration was influenced by European pattern books or, like the alterations to Kirby Hall, Northamptonshire, in 1638–40, nodded to the Classical style of Greece and Rome.

INIGO JONES

Inigo Jones (1573–1652) was the first English architect who fully embraced Classicism.

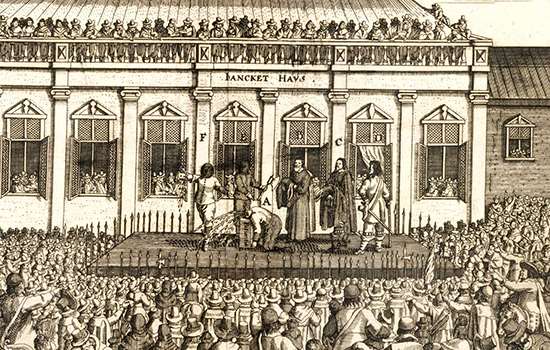

His immensely influential buildings were based closely on ancient Roman or Italian Renaissance models. Best-known is the Banqueting House in Whitehall, London (1619–22), from whose window Charles I walked onto his execution scaffold in 1649.

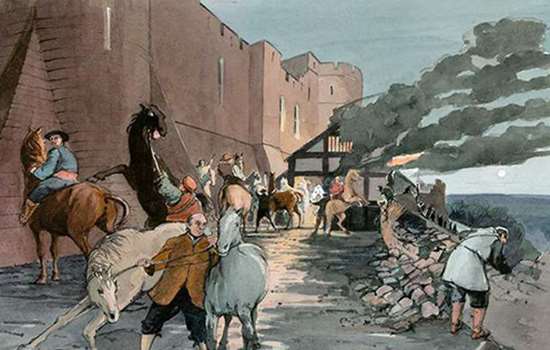

SLIGHTING

By the end of the Civil Wars in 1651, countless buildings throughout England had suffered either in sieges or from ‘slighting’ – damage ordered by Parliament to render them indefensible. Locals enthusiastically joined in, gaining free building materials in the process.

Other people, such as the formidable Lady Anne Clifford, were keen to rebuild. Her post-war restorations in the north-west included Brough Castle and her favourite, Brougham Castle.

COMMONWEALTH STYLE

People continued to build new country and town houses throughout and beyond the Interregnum (1649–60).

Their so-called Artisan Mannerist design was often an eclectic but charming blend of Jacobean, ‘Classical’ and Dutch/Flemish styles. Its characteristics were tall hipped roofs with gabled dormers, like those that adorn the Riding School range at Bolsover Castle; symmetrically arranged cross-mullioned windows; and decorative (and often huge) ‘pilaster columns’, like those at Abingdon County Hall, Oxfordshire.

CHURCHES

Few new churches were built during the early Stuart period, though existing ones were internally adapted for Protestant worship. Langley Chapel, Shropshire, with its full set of Jacobean furnishings, is a fine example.

The Great Fire of London of 1666 destroyed 87 of the city’s 108 churches, giving Sir Christopher Wren the opportunity to start again from scratch. His 50 or so replacement churches represent a series of experiments in purpose-built Anglican church design, rejecting the old models. They are adorned with an astonishing variety of pinnacles, columns, rotundas and obelisks – and in the case of Wren’s masterpiece, St Paul’s Cathedral, an extraordinary dome.

PAVILIONS AND PALACES

Wren’s architectural sources included the European Baroque, whose more flamboyant excesses never really caught on in England. But Thomas Archer’s magnificent 1711 pavilion at Wrest Park in Bedfordshire was strongly influenced by the style; and to a lesser extent so was the plainer Appuldurcombe House on the Isle of Wight, begun in 1702.

The last years of Stuart architecture are dominated by the ‘amateur’ soldier-playwright-architect Sir John Vanbrugh and his professional partner Nicholas Hawksmoor, designers of Castle Howard, Yorkshire (1699–1726), and the Duke of Marlborough’s stupendous Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire (1705–16). Their influence continued into the Georgian period.

More about Stuart England

-

Stuarts: Architecture

From the grand country houses of the early Stuart period to Christopher Wren's new churches that rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

-

Stuarts: Commerce

The economy of much of Stuart England was largely based on traditional industries. London, however, was at the centre of a growing international network of trade.

-

Stuarts: Parks and Gardens

The influence of the great formal gardens of the Renaissance gradually gave way to the opulence of the Baroque during the Stuart period.

-

Stuarts: War

How the reorganisation of the Parliamentary army following the devastating Civil Wars of 1642–51 was the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.

Stuarts Stories

-

The English Civil Wars

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

-

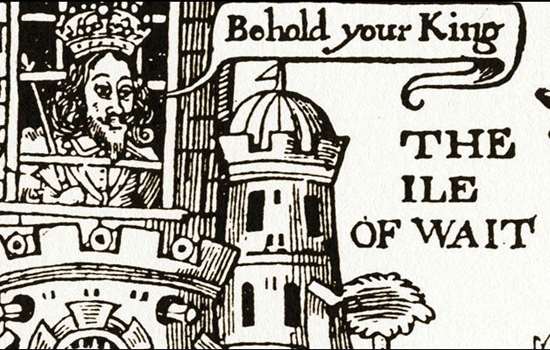

Charles I: a Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle

Learn about Charles I’s time as a prisoner of Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.

-

The Siege of Goodrich Castle

In June and July 1646, Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the Civil War.

-

THE SIEGE OF DONNINGTON CASTLE

Discover how Donnington Castle in Berkshire held out for Charles I during a 20-month siege in 1644–6, and played a key role in the Second Battle of Newbury.

-

Charles II and the Royal Oak

How the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War in 1651, giving English history one of its greatest adventure stories.

-

Blanche Arundell, Defender of Wardour Castle

Read about how Lady Blanche Arundell heroically led a small band of men and women in defence of her home, Old Wardour Castle, when it came under siege during the Civil War.

-

The King and his Favourite

George Villiers became a favourite of King James I after their first meeting at Apethorpe in 1614. Read about James and George and the surviving love letters between them.

-

Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was one of the most prolific female authors and philosophers of the 17th century, writing at a time of immense political upheaval.