Stuarts: Commerce

Throughout the 17th century England’s economy remained largely based on agriculture and traditional industries. London, however, was at the centre of a growing international network of trade, both with the East and with colonies across the Atlantic.

CITY AND PROVINCES

Stuart London was the biggest and fastest-expanding city in Europe, drawing in about 6,000 newcomers from the provinces annually. Its population rocketed from about 200,000 in 1600 to about 575,000 in 1700 – 11% of the total English population.

Many of Stuart England’s much smaller provincial towns were also growing. Among the largest were Bristol – second only to London and the premier English seaport – Norwich and Newcastle. Growth hinged on commerce: Newcastle, with a population of about 16,000 by the 1690s, sent coal from the Durham mines to London.

Towns that drew their wealth from the traditional wool and cloth industries, such as Gloucester, metropolis of the Cotswold wool trade, continued to flourish. Rising industrial communities included cloth-weaving Manchester and metalworking Birmingham, whose population quadrupled to 8,000 in Stuart times. Fishing ports like Great Yarmouth in Norfolk also prospered, and their harbours thronged with ships.

MONOPOLY CAPITALISM

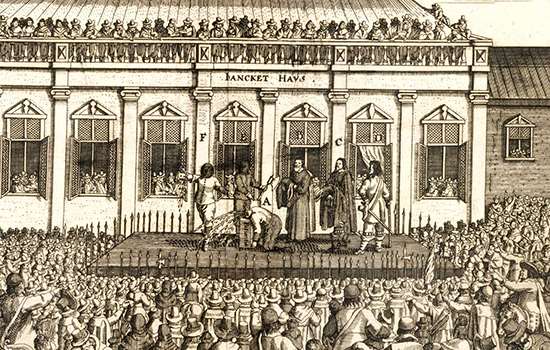

Early Stuart governments cashed in on commerce by selling exclusive ‘monopolies’ on trading in specific goods, thus fixing their retail price. Bitterly unpopular, monopolies were abolished in 1624 by James I’s last Parliament, but Charles I’s ministers, desperate for money, reintroduced them as ‘patents’.

Especially resented was the patent on producing soap, which allowed the suppression of supposedly inferior rival products. In Bristol, a laundress and a tavern maid publicly demonstrated that local soap washed whiter than patent soap.

ENTREPRENEURS AND AMERICA

During the Civil Wars suppliers of weapons and military equipment prospered. They could not meet increased demand, however, and the Royalists in particular had to import foreign arms. To provide the food and clothing they needed for their armies, both Royalists and Parliamentarians relied on entrepreneurial general contractors, who ‘bought in’ at a profit from subcontractors.

Such contractors were already offering to equip emigrants to America with all they needed, from warm boat-cloaks and pickled pork to wheelbarrows. In the course of the 17th century over 300,000 people – both religious and economic migrants – left England, crossing the Atlantic to colonies in the West Indies and North America.

Trade with these colonies grew rapidly, especially after the Restoration, with imports including sugar, tobacco and other exotic foodstuffs such as cocoa. The Hudson’s Bay Company, chartered in 1670 by Charles II, grew rich through control of the fur trade: at one time it claimed 15% of the territory of North America, making it the largest landowner in the world.

TRADING COMPANIES

The vessels of the great trading companies, many established under Elizabeth I, expanded the English commercial empire eastwards too. The Muscovy Company traded with Moscow; the Levant Company prospered in Constantinople; and East India Company ships brought tea and silk, indigo and opium from India.

The Muscovy Company (which had been founded in 1552) was the first major joint-stock business, in which merchants banded together to share financial risks and thus take on more ambitious ventures. The origins of the London Stock Exchange can be traced to the trading of shares in these companies in 17th-century coffee-houses.

HUGUENOTS

Though more people emigrated than immigrated during the 17th century, French Protestant Huguenots, fleeing persecution by Louis XIV, were making their mark on English commerce.

They included many skilled craftsmen, particularly silk weavers. They established colonies in Bristol, Canterbury and especially around Spitalfields and Soho in London. By 1700 they made up 5% of the capital’s population.

More about Stuart England

-

Stuarts: Architecture

From the grand country houses of the early Stuart period to Christopher Wren's new churches that rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

-

Stuarts: Commerce

The economy of much of Stuart England was largely based on traditional industries. London, however, was at the centre of a growing international network of trade.

-

Stuarts: Parks and Gardens

The influence of the great formal gardens of the Renaissance gradually gave way to the opulence of the Baroque during the Stuart period.

-

Stuarts: War

How the reorganisation of the Parliamentary army following the devastating Civil Wars of 1642–51 was the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.

Stuarts Stories

-

The English Civil Wars

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.

-

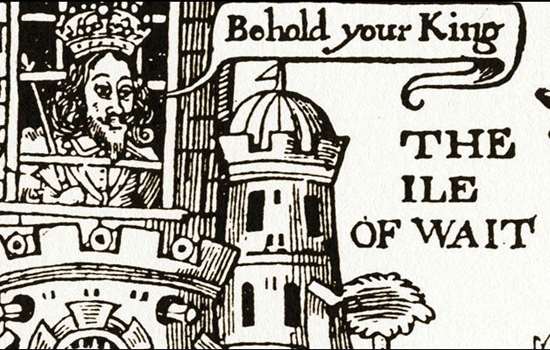

Charles I: a Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle

Learn about Charles I’s time as a prisoner of Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.

-

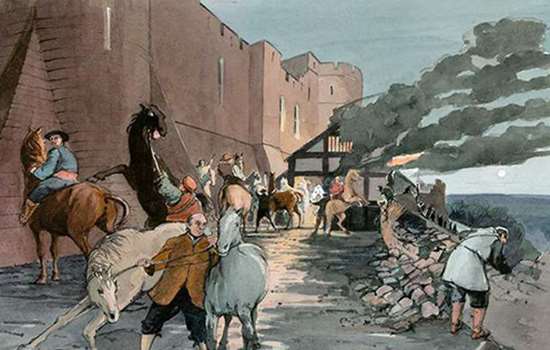

The Siege of Goodrich Castle

In June and July 1646, Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the Civil War.

-

THE SIEGE OF DONNINGTON CASTLE

Discover how Donnington Castle in Berkshire held out for Charles I during a 20-month siege in 1644–6, and played a key role in the Second Battle of Newbury.

-

Charles II and the Royal Oak

How the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War in 1651, giving English history one of its greatest adventure stories.

-

Blanche Arundell, Defender of Wardour Castle

Read about how Lady Blanche Arundell heroically led a small band of men and women in defence of her home, Old Wardour Castle, when it came under siege during the Civil War.

-

The King and his Favourite

George Villiers became a favourite of King James I after their first meeting at Apethorpe in 1614. Read about James and George and the surviving love letters between them.

-

Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was one of the most prolific female authors and philosophers of the 17th century, writing at a time of immense political upheaval.