Tudors: Architecture

The architecture of early Tudor England displayed continuity rather than change. Churches great and small were built in the Perpendicular Gothic style of the later Middle Ages. Later in the 16th century, however, the great country house came into its own.

GOTHIC TO RENAISSANCE

Some of the finest examples of Perpendicular Gothic – particularly Henry VII’s chapel in Westminster Abbey – belong to the early Tudor period.

By the early decades of the 16th century, however, a distinctively Tudor form of Perpendicular had developed. This was characterised by flatter arches, with four centres rather than steep points, and by window tracery with rows of narrow round-headed lancets.

A more significant presage of change was the appearance of motifs derived from Classical antiquity, an English reaction to the Renaissance style sweeping western Europe. At first largely cosmetic (like the ‘Roman’ heads applied to panelling or plasterwork), such features filtered down from great royal palaces like Hampton Court via courtiers’ mansions like Acton Court in Gloucestershire, extended in 1535 specifically to receive Henry VIII.

GREAT HOUSES

Since few churches were built after the Reformation – though existing ones were reordered internally to accord with changes in religion – it was in such mansions that the future of architecture lay.

Among the earliest of these were houses built by men enriched through the Suppression of the Monasteries. Some (like Titchfield Abbey in Hampshire) were adapted monastic buildings. Others were built on monastic sites, like the first Audley End, Essex.

The great country house came into its own in the later 16th century, when some of the most famous and impressive mansions in England – including Longleat and Burghley House – were built.

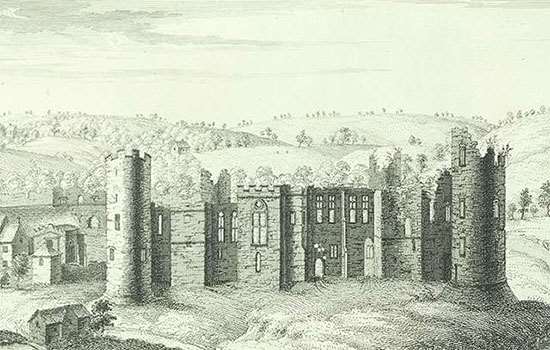

Others were raised within the walls of medieval castles, like the compact Elizabethan mansion at Berry Pomeroy Castle, Devon, the dramatic Elizabethan-Italianate range at Moreton Corbet Castle, Shropshire, and spectacularly at Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, where Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, spent fortunes on lavish new buildings to impress Elizabeth I.

WONDER HOUSES

To impress and astonish was the aim of great Elizabethan mansions. This could best be achieved by building on new sites and in the Classical-Renaissance style, which had by now shaken off the influence of Gothic.

As England was largely cut off from Catholic Europe, printed pattern books were the main means by which English patrons encountered the new style. A new breed of men – architects – emerged to translate these new ideas into reality.

The effect of ‘prodigy’ or ‘wonder’ houses might be enhanced by features like showy porches (as at Old Gorhambury House, Hertfordshire, and Kirby Hall, Northamptonshire), chimneys (as at Framlingham Castle, Suffolk) or huge expanses of glass, as at Hardwick New Hall, Derbyshire. The latter was erected by the fabulously rich Bess of Hardwick beside Hardwick Old Hall (1587–96), which she had built in place of her father’s medieval manor house.

Other buildings impressed by their strikingly innovative design, like Sir Thomas Tresham’s Rushton Triangular Lodge, Northamptonshire, where everything comes in threes to symbolise the Trinity, proclaiming the builder’s defiant Catholic faith. Elizabethan architecture in general was obsessed with geometrical shapes, patterns and ‘devices’.

THE MIDDLING SORT

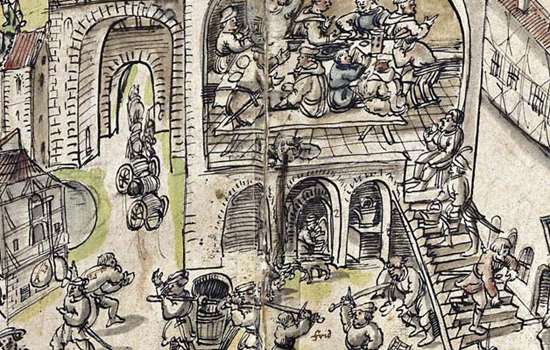

The Tudor period also saw an explosion of more modest new houses being built in town and country, as merchants, squires and rich farmers celebrated burgeoning commerce and improving standards of daily life.

Outside the stone-built north and west and the brick-favouring eastern counties, houses continued to be timber-framed, sometimes with several ‘jettied’ storeys, each projecting beyond the one below. Timbering was frequently plastered or lime-washed over or embellished with elaborate carving (perhaps surprisingly, exposed black-painted timbers were largely a Victorian fashion).

The lesser – as well as the greater – houses of the period could be said to reflect England’s exuberance and growing self-confidence.

More about Tudor England

-

Tudors: Parks and Gardens

Tudor parks and gardens provided an opportunity for dramatic displays of newly found wealth, success and power.

-

Tudors: Architecture

The architecture of early Tudor England displayed continuity rather than change. Later, however, the great country house came into its own.

-

TUDORS: RELIGION

The Tudor era witnessed the most sweeping religious changes in England since the arrival of Christianity, which affected every aspect of national life.

-

Tudors: War

The Tudor period saw England's medieval army evolve into a larger, firearm-wielding force supported by powerful ships and formidable gun forts.

Tudor stories

-

The Suppression of Roche Abbey

How a vivid eyewitness account reveals the shocking speed and scale of destruction of Roche Abbey after the Suppression of the Monasteries.

-

Walter Hungerford and the 'Buggery Act'

In 1533 Henry VIII’s government introduced the ‘Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie’. Less than ten years later, Walter Hungerford became the first man to be executed under its terms.

-

Lady Anne Clifford

The last member of one of England’s great medieval dynasties, Lady Anne Clifford became something of a legend in her own lifetime.

-

Lydford Law and Parliamentary Privilege

From a Tudor ‘tinner’ to a 21st-century footballer: how the Privilege of Parliament Act can be traced back to the ghastliness of prison life at Lydford Castle in Devon.

-

The Rise and Fall of a Tudor Wool Factory

How the Heydon family of Baconsthorpe Castle in Norfolk made a fortune from the East Anglian wool trade – and then lost it all.

-

Mary Queen of Scots at Carlisle Castle

Find out why, after Mary Queen of Scots fled to England in 1568, her two-month stay at Carlisle Castle began 19 years of captivity.

-

Bess of Hardwick

Rising from a modest background to become one of the richest women of her time, Bess was also a tireless and ambitious builder, whose houses symbolised her rise to wealth and power.

-

Sir Peter Carew and Dartmouth Castle

How a centuries-old stand-off over a castle provoked Tudor soldier and adventurer Sir Peter Carew into trying to outwit the borough of Dartmouth.

-

Lambert Simnel and Piel Island

How a Yorkist claimant to the English throne failed to usurp Henry VII in the final chapter of the Wars of the Roses.