Meet Our Expert

My name is Olivia Fryman and I’m a Curator of Collections and Interiors for English Heritage. I help care for more than 6,500 objects in the collection at Down House, the home of Charles Darwin. I also look after the collections at two other sites in London: Eltham Palace and Ranger’s House.

Down House has been a museum to Darwin’s life and work since 1929. The collection and the historic interiors of the house provide a fascinating insight into family life at Down, Darwin’s research and methods of work that led to his groundbreaking theory of evolution. We look after many of Darwin’s scientific instruments and manuscripts, as well as personal possessions such as his top hat and snuff jar. One of my favourite objects is Darwin’s writing chair, a rather oddly shaped mahogany armchair on castors in the study, from where he wrote On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859) and many of his other publications.

I began working in museums and historic buildings after studying History and History of Design at university. I've always loved experiencing historic buildings and collections as both a curator and visitor. It's a great privilege to be able to work at Down House, the place where our understanding of the natural world was revolutionised by a now world famous scientist.

- Olivia Fryman, Curator of Collections and Interiors (Ranger's House, Down House and Eltham Palace)

Charles Darwin's Writing Chair

Date: c.1835

Description: We can discover a lot about a person by the objects they used in their everyday lives. This is especially true of this unusual mahogany armchair used by Charles Darwin. It's one of the original pieces of furniture from Darwin’s Old Study, the room in which he wrote his groundbreaking theory of evolution, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, published in 1859.

Darwin positioned the chair at one corner of his work table and wrote hunched over a cloth-covered writing board that he balanced across the chair arms. We can see how the chair was used by looking at how it's been worn over time. The arms have been patched in places where the original fabric has been worn away by the pressure and movement of the board.

To make the chair more suited to Darwin’s height and long legs (he was over 6ft tall), he had it raised up on cast-iron legs taken from an old bedframe with a wooden strut nailed roughly across the front to support the back of his knees. The chair also had casters to allow him to move easily about the study from one workspace to another.

Further Learning Idea: Think about how you might change a piece of furniture to better suit your everyday life. Consider its form and function and any additional features you think might be useful to you. Create a labelled drawing explaining your choices.

Charles Darwin's Pocket Microscope

Date: c.1831

Description: This pocket microscope was used by Charles Darwin to examine specimens during his time on board HMS Beagle. Between 1831 and 1836 the crew of the Beagle sailed around the world to explore, map and record remote lands rarely travelled to by Europeans. As a naturalist, it was Darwin’s job to observe and collect specimens of plants, animals, rocks, and fossils wherever the expedition went ashore. He later used his findings to develop his theory of evolution.

Darwin’s pocket microscope has a tiny pair of tweezers for picking up specimens and two probes for holding them in place on the disc in the middle. It could be safely carried in his pocket or bag inside its black cardboard case.

After Darwin’s death, many of his scientific instruments were labelled by his children who wanted to preserve their famous father’s memory. The case of this microscope has a label on the outside that reads ‘microscope used by CD on Beagle’.

Further Learning Idea: Find out more about Darwin's experiences on HMS Beagle. You could chart the Beagle's journey on a map and explore the different species and phenomenons that Darwin observed on his travels.

Stair Slide

Date: c.1842

Description: Down House may have been Charles Darwin's laboratory but it was also a happy family home. He commissioned the Downe village carpenter, Mr Lewis, to make this stair slide soon after the family moved to Down House. By this time Emma Darwin had given birth to two children, William and Annie, and went on to have a further three girls and five boys. Eight of the Darwin’s children survived early infancy and were brought up at Down House under the care of their governess, Miss Thorley.

Contrary to the familiar Victorian saying that “children should be seen and not heard”, the young Darwins were encouraged to express themselves freely and spent a lot of time with their mother and father. Charles and Emma were unusually broad-minded Victorian parents because of their own liberal upbringings. The slide was designed to fit the lower section of the main staircase, and would have been enjoyed by all of the Darwin children. There are even records of Emma and Miss Thorley trying it out.

Further Learning Idea: Find out more about the forces at work when we use play equipment like the Darwins' slide at Down House. You could draw a labelled diagram showing how these forces operate when someone slides down a slide.

Daguerreotype of Annie Darwin by Antoine François Jean Claudet

Date: 1849

Description: Down House's collections reflect the highs and lows of family life as well as changes in technology during the Victorian period. The paper label fixed to the glass identifies this picture as Annie, the Darwins’ eldest daughter. It was taken when she was eight years old at Claudet’s photographic studio in London. Known as ‘sun pictures’, daguerreotypes were invented by Louis Daguerre in 1839, not long after the invention of photography itself. Daguerre’s method involved exposing a light sensitive emulsion coated over a polished metal plate to fix an image. It was not possible to duplicate a daguerreotype; each was unique. As singular objects they were intended for display on a family mantelpiece.

Annie Darwin fell seriously ill in 1849 and despite receiving the latest medical treatments she died shortly after her 10th birthday in 1851. Charles and Emma were devastated by her loss. Charles wrote in a memorial to her:

‘We have lost the joy of the Household, and the solace of our old age:— she must have known how we loved her; oh that she could now know how deeply, how tenderly we do still & shall ever love her dear joyous face’.

Further Learning Idea: Explore the history of photography and set up your own photograph, just like a Victorian photographer in their studio. Think about any props or backgrounds you want to use and how you want your sitter to pose.

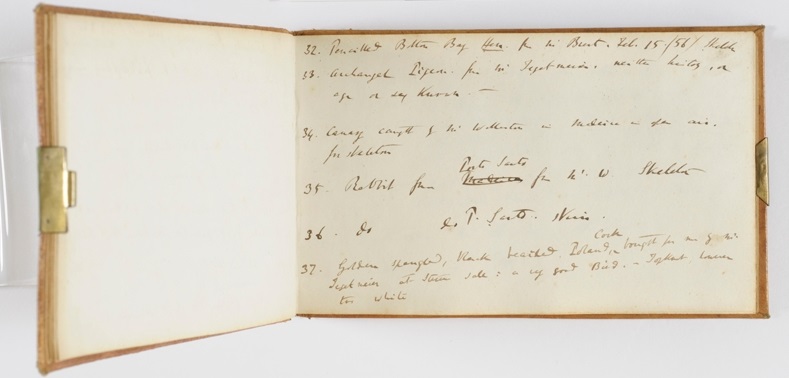

Experiment Notebook

Date: 1855-59

Description: Records of Darwin's experiments reveal his sometimes rather odd working methods and the development of his research on evolution.

From March 1855, Darwin made notes on the experiments he carried out at Down House. He recorded his findings about the plants and animals in his house and gardens in small leather bound books, like this one. In one experiment, he laid damp sheets of paper, covered in frogs spawn, up and down the hall next to his study to see how long it would remain viable. After three days, he returned the dried-up frogs spawn to water but found that it didn't rehydrate.

Darwin also tried a similar, more successful, experiment with freshwater snails that he encouraged out of an aquarium onto a pair of amputated ducks' feet. He concluded that these particular snails survived for 17-20 hours out of water, potentially enabling them to travel to new environments on the feet of waterfowl as they flew.

Further Learning Idea: Take on the role of a scientific researcher in your garden or local area. Make notes just like Charles Darwin did in his notebooks. Observe the wildlife you see on a local walk or investigate your garden or local park to discover the species of plants growing there. What do you notice about your findings?

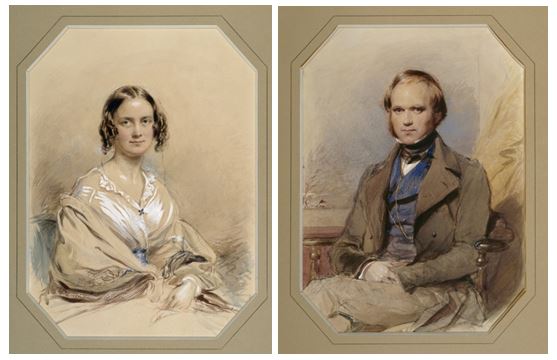

Charles and Emma Darwin Portraits by George Richmond

Date: c.1839

Description: This pair of portraits shows Charles and Emma Darwin shortly after their marriage in 1839. As first cousins, they had known each other since childhood and went on to enjoy a very happy, loving marriage for 43 years until Charles’ death in 1882. Charles had been unsure about the idea of marriage and even wrote himself a long list of the pros and cons of acquiring a wife. One of his chief concerns was that he would no longer have the time and freedom to study, a worry that proved unfounded. Throughout Darwin’s life, Emma did a great deal to support him in his scientific work and nursed him through long periods of ill health.

In contrast to many portraits of Darwin that show him in later life, this painting by Richmond shows him when he was 30 years old, long before he grew his iconic white beard. It’s an important reminder that as well as a great scientist, Darwin was also a loving husband to Emma and father to their 10 children.

Further Learning Idea: We can tell a lot about people from how they are portrayed in paintings and photographs. Compare these marriage portraits of the Darwins with later photographs of Charles and Emma. What key differences can you spot? Why do you think you might be more familiar with these later photographs?