Meet our Expert

My name is Louise Cooling and I’m Assistant Curator at Kenwood. This means that I help to look after more than 8,000 objects in the collection at Kenwood.

Kenwood is home to an outstanding collection of fine and decorative arts, we also look after more unusual objects, including the world’s largest collection of 18th-century shoe buckles. One of my favourites is a little portrait miniature by John Smart. It’s so incredibly detailed and lifelike despite being so small, and I love the sitter’s pale pink powdered hair.

I began working with collections after studying History of Art at university. It’s very special to work with a collection in a historic space like Kenwood, where the architecture, furniture and art all work together in context to tell a story.

- Louise Cooling, Assistant Curator at Kenwood

Library Ceiling

Date: 1769

Description: Sometimes you can find clues about the history of a site and the people that lived there in unusual places, like the group of 19 paintings that decorate the ceiling of the Library or ‘Great Room’ at Kenwood. They were painted by the Venetian artist Antonio Zucchi as part of a lavish decorative scheme designed by the celebrated neo-classical architect Robert Adam. Adam was employed to remodel Kenwood in the 1760s and 1770s by the house’s owner, William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield. The Library was the most important room at Kenwood. It was intended ‘for receiving company’ and was used by the family to host dinners, perform music, and play games with their guests.

It's likely that Lord Mansfield collaborated with Robert Adam and Antonio Zucchi to devise the scheme of paintings in the Library, giving us an insight into how he wished to present himself and his achievements through the art in his home. William Murray was Lord Chief Justice, the most senior judge in England and one of the most important legal figures of his day. The subjects chosen for the ceiling paintings allude to Lord Mansfield’s profession. The central oval shows the Greek demi-god Hercules choosing a life of virtue over one of pleasure, representing wise judgement. Other paintings depict symbolic figures of Justice, Theology, Jurisprudence (the theory of law), Mathematics and Philosophy, as well as scenes from classical mythology. Altogether, the paintings are intended to show that Lord Mansfield was a cultured man and a wise judge.

Further Learning Idea: Find out more about Robert Adam's style and his influence on Georgian design. Use our learning activity to design your own interior inspired by Adam's use of classical motifs.

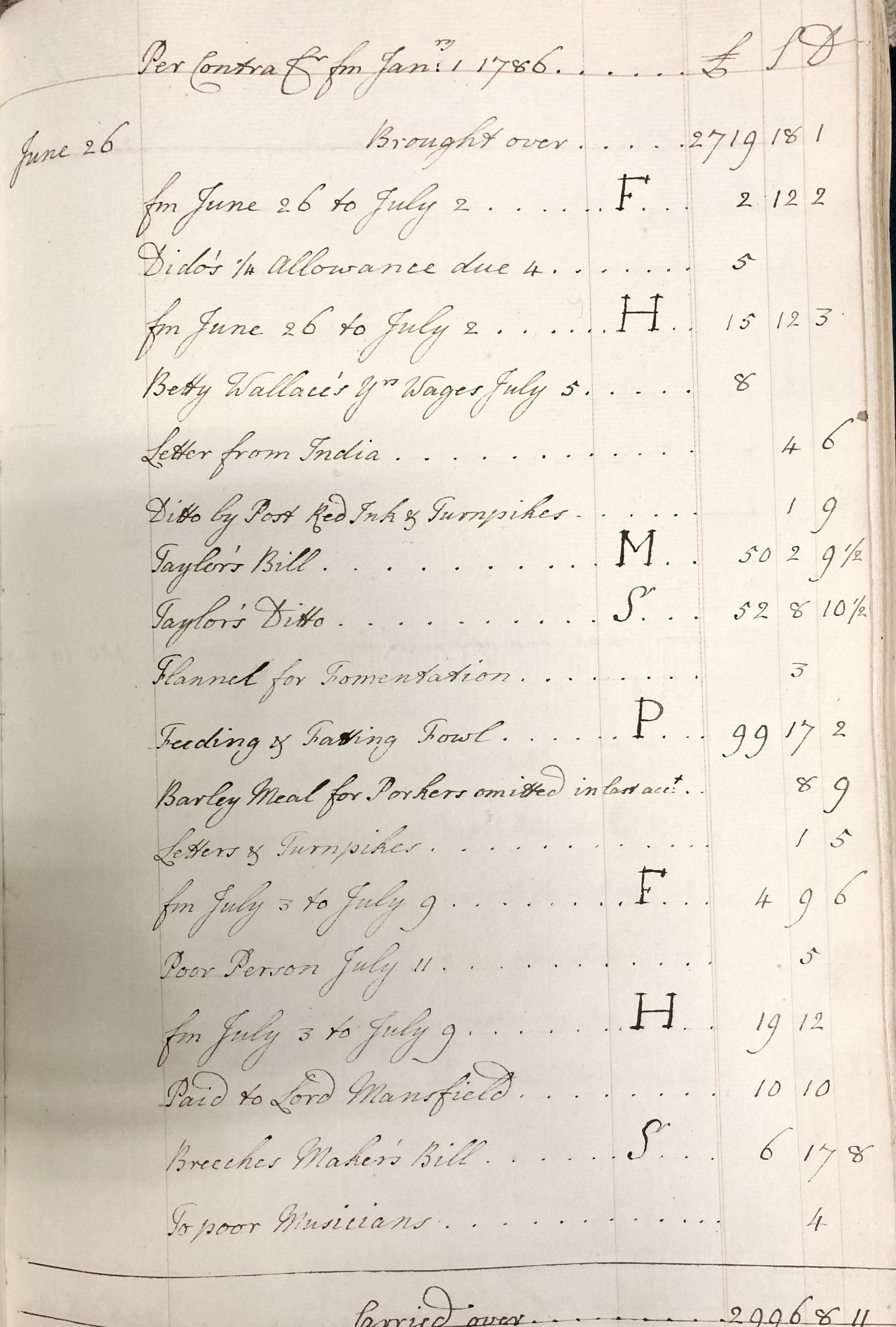

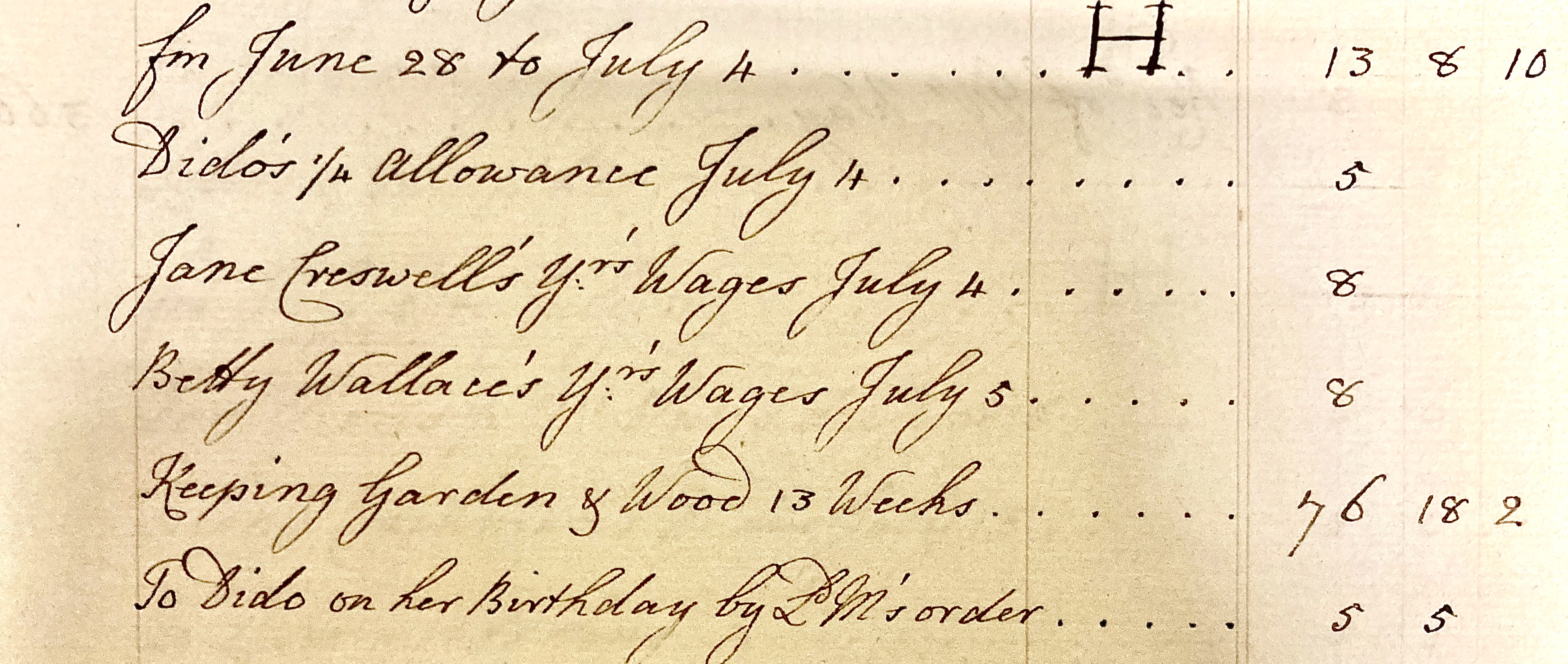

Lady Anne Murray's Household Accounts

Date: 1784-93

Description: As well as art objects, the collection at Kenwood includes historic documents and archival material, which can give us an insight into the lives of the people who once called Kenwood home.

This book of household accounts was kept by Lady Anne Murray, who lived at Kenwood in the late 18th century. It details all of the household income and expenditure between 1784 and 1793. During this time, Kenwood was home to Dido Elizabeth Belle. Dido was the illegitimate, mixed-raced daughter of Lord Mansfield’s nephew, Sir John Lindsay, an officer in the Royal Navy, and an African woman named Maria Belle. Dido came to live at Kenwood when she was around five years-old and was raised by her great-uncle and aunt, Lord and Lady Mansfield.

The household accounts give us insights into Dido’s life at Kenwood and her relationships with members of her family. They reveal that Lord Mansfield gave Dido an annual allowance of £20 – roughly £1,535 today. This was a personal allowance – like pocket money – that Dido could save or spend on things she wanted.

Lord Mansfield also gave Dido an extra five guineas (just over £5) for her birthday in June and for Christmas. The account book shows that this was more than five times what Lord Mansfield gave to his other nieces and nephews on special occasions, suggesting that he and Dido were particularly close.

Further Learning Idea: Research Dido's life and her experience of Kenwood in the 18th century by exploring our online resources. Use your new knowledge to create a guidebook entry including all the information you think people should know about Dido.

'The Guitar Player' by Johannes Vermeer

Date: c.1672

Description: The 17th century is known as the 'Golden Age' of Dutch art and Johannes Vermeer is considered one of the greatest painters of the period. He specialised in scenes of quiet, domestic life in middle-class homes. In this painting, an elegantly dressed young woman is interrupted as she plays the guitar, the strings of which are slightly blurred, as though still vibrating with music. Vermeer uses a ‘close up’ effect to draw us into the scene, painting the figure so far forward that her knee seems to push out of the picture towards us. The artist doesn’t reveal the source of the interruption, instead as viewers we’re left to imagine what might have distracted the young woman from her playing.

Despite being celebrated in his own lifetime, Vermeer was largely forgotten for almost 200 years after his death, until his work was rediscovered and re-evaluated in the 19th century. When Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, bought this painting in 1889, Vermeer’s reputation was on the rise. Purchasing the painting when he did was a way to demonstrate Lord Iveagh’s fashionable taste and eye as an art collector. Vermeer’s work is extremely rare even today. The Guitar Player is one of only five paintings by Vermeer in the UK and only 34 are known to survive in the world.

Further Learning Idea: Imagine that you're an art collector like Lord Iveagh. Research an artist working currently and write an art review of one of their works. Make sure you include an introduction to the artist and explain what you like or dislike about the piece.

'Mary, Countess Howe' by Thomas Gainsborough

Date: c.1764

Description: Works of art, especially portraits, can tell us a lot about the tastes and fashions of the time in which they were made. Thomas Gainsborough’s painting of Mary, Countess Howe (1732-1800), is one of the most famous portraits of the 18th century. Unlike his great rival, Joshua Reynolds, who preferred to paint his sitters in timeless costumes inspired by classical antiquity, Gainsborough’s portrait shows Countess Howe in all the latest fashions. Her pale pink silk dress, worn over a corset and matching silk bodice, is in a style known as a ‘nightgown’ or ‘robe á l’anglaise’. In the later 18th century this style of dress was considered informal and was worn by aristocratic and upper-class women in everyday life.

Lady Howe’s outfit includes more than a dozen accessories, intended to demonstrate her wealth and fashionable taste. Her striking wide brimmed sunhat was most likely imported from Italy. The style was inspired by the hats traditionally worn by working women in rural areas and reflects the idealisation of rural life by the fashionable upper classes in the mid-18th century.

As well as accessories, Countess Howe is probably also wearing cosmetics to enhance the paleness of her skin. A pale complexion was fashionable at the time because it showed that a person was wealthy and did not have to work outdoors, where they would become tanned. Lady Howe would have used an ointment made with lemons, egg white, almonds and poisonous ingredients like white lead and mercury; this would have been set with a dusting of powder made from ground pearls. The black velvet bracelet worn by Countess Howe in the portrait was also intended to emphasise her pale skin.

Further Learning Idea: Consider the difference between clothes that were considered fashionable in the 18th century and what's considered fashionable today. Think about how you would depict Mary, Countess Howe if she were alive now and create a portrait of her incorporating fashions from the 2020s. Think about the materials, accessories, shoes and jewellery that you think reflect 21st-century fashion.

Skeleton Clock

Date: 1776

Description: One of the more unusual objects in the collection at Kenwood is a late 18th-century clock, known as a skeleton clock because it has no outer casing, so we can see the inner clockwork mechanism. It's the earliest skeleton table clock to survive anywhere in the world and was made by an eccentric inventor or ‘mechanick’ named John Joseph Merlin. As well as making clocks and watches, Merlin also made musical instruments, mechanical furniture, including an early example of a wheelchair, and even an early pair of roller-skates. He was also the proprietor of ‘Merlin’s Mechanical Museum’, where his inventions and ‘scientific toys’ were displayed. After opening in the 1780s the museum quickly became one of London’s most popular attractions, helped by the tours Merlin would give in fancy dress costume.

It seems likely that Merlin created the skeleton clock for exhibition, rather than for sale and it may possibly have been displayed at his Mechanical Museum. Merlin likely chose a skeleton design in order to allow potential customers to appreciate his ingenious and experimental approach to clockmaking.

One of Merlin’s patrons was David Murray, who became the 2nd Earl of Mansfield. He purchased a personal weighing machine designed by Merlin and brought it with him to Kenwood in the 1790s. Merlin is known to have visited Kenwood in the 1780s to repair and tune several musical instruments in the house.

Further Learning Idea: Take on the role of an inventor like John Joseph Merlin and develop an idea for a new machine. It could be anything you like – maybe something to help you with everyday tasks or something to help others who live in a different environment to you. This could be a different country, landscape, or even something for people in the future.

Grecian Pedal Harp

Date: 1828

Description: We know from historic inventories describing the contents of Kenwood that in the late 18th century the Murray family owned a pedal harp similar to this one. It was just one of a number of musical instruments at Kenwood; there was also an organ, two pianos, a guitar and several tambourines.

Harps like this one, which was designed and made by Sébastian Érard, a leading instrument maker, were most often played by women. In the 18th and 19th centuries music was considered an appropriate pastime for women, who did not have the same rights or status in society as men and who were often not allowed to work. Middle and upper-class women were expected to study music and to be accomplished at playing instruments or singing, so that they could entertain their family and friends. It was also thought that being an accomplished amateur musician could help young unmarried women attract husbands.

Owing to their sweet, harmonious sounds, harps became particularly popular instruments for women and there are many portraits and prints showing women playing the harp.

Further Learning Idea: Find out more about the science behind how the vibrating strings in harps make their sound. You could make your own example of a stringed instrument to observe this in action.