A Mysterious Foundation

The Priory of St Leonard in Brewood was founded in the late 12th century in Brewood Forest, then a remote wooded area. It was a house of Augustinian canonesses, who followed the relatively mild Rule of St Augustine. It was known as White Ladies from the colour of their robes, to distinguish it from the Benedictine convent of St Mary, Brewood, about a mile away, known as the Black Ladies. The Black Ladies were in the manor of Brewood in Staffordshire, held by the Bishop of Lichfield, while the site of the White Ladies – now in the county of Shropshire – found itself in the unusual position of not being in either a parish or a manor at the time.

It is not known when the priory was founded or who the founder was. There must have been a wealthy patron, for a stone church about 35 metres long was built, apparently in a single campaign. However, the founder did not give the house any substantial endowment of property, and White Ladies was always a poor house: the nuns were not able to engage in significant building projects again, and their church had been little altered when the house was suppressed in 1536. The first recorded reference to it is in about 1186.

It may be that the unusual dedication bears a clue to White Ladies’ foundation, for St Leonard was the patron saint of captives: his attribute is a set of shackles. The priory may have been a thank-offering by a wealthy man or woman, freed from captivity. It may be that research will one day shed light on this question.

A Poor Community

White Ladies was a small community: it normally had around five nuns and a prioress. They had a chaplain to celebrate Mass, who received a salary of £5 a year. There were probably several lay servants, to do the practical jobs. Over time the nuns were given numerous small pieces of property, in the area south and west of Brewood (in south Shropshire), by a variety of donors. They held the churches at Montford, near Shrewsbury, and at Tibshelf in Derbyshire and Bold in Shropshire. King John gave them a weir on the river Severn. No one ever claimed the patronage of the house, but it may be that the White Ladies had links to the powerful de Lacy family (lords of the manor of Montford), and to the Zouches of Ashby de la Zouch in Leicestershire.

The Augustinian religious houses did not have a hierarchy like other religious orders: White Ladies was under the supervision of the Bishop of Lichfield, who came to inspect periodically. Bishop Northburgh, a reforming figure, intervened at White Ladies several times. In 1326 he threatened two canonesses who had left without permission with excommunication. In 1332 he cancelled the election of a new prioress, Alice de Harley, suspecting that it had been improperly conducted, but re-appointed her on his own authority. However, in 1338 he returned to reprimand Alice for financial mismanagement, extravagant dress, living in her own chambers rather than with the nuns, and for hunting with dogs.

In the later Middle Ages the priory was obliged to let most of its property on long leases at fixed rents. This put its finances under strain. When Prioress Alice Wood retired in 1498 she was given the revenue of Tibshelf, about a fifth of the priory’s income, as a pension.

A visitation in 1521 found that the convent was free from debt, but the prioress, Margaret Sandford, did not know how to keep accounts, the nuns’ salaries had not been paid, and the buildings were in disrepair. At this date, the seneschal or steward of White Ladies was Sir Thomas Giffard of Chillington and Caverswall (1491–1560), a Tudor courtier and leading local landowner.

Dissolution and Adaptation

In 1535 when the house was visited by official assessors its revenues were only £31 1s. 4d. Expenses, including the chaplain’s salary, only amounted to £13 10s: evidently the nuns lived very frugally. Its income brought it within the terms of the Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries Act of 1536, and the house was ordered to be closed in the same year. However, there were still four canonesses in residence in 1538. The last prioress, Margaret Sandford, received a pension of £5.

The priory and its core estate were let for 21 years to William Skeffington, but the reversion or freehold was sold in 1540 to William Whorwood, the Crown’s Solicitor General. Skeffington apparently resided there, and was buried in nearby Tong church in 1550. It was probably him who dismantled the priory buildings and built the timber-framed manor house which appears in later views. Skeffington’s widow, Joan, married Edward Giffard, the second son of Sir Thomas Giffard, conveying the estate to him. At some point, the Giffards must have bought the freehold. It was Edward Giffard’s son, John, who built Boscobel House, as a subsidiary residence or lodge, about a mile away, in about 1620–30.

The White Ladies estate passed by descent until 1812: when it was sold in that year it covered 659 acres (267 hectares), which may well represent the 16th-century estate, and the original land of the priory.

A Moment of Fame

White Ladies’ one moment of historic fame arrived when the young king Charles II took refuge there after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651, in the Third Civil War. Charles was greeted early in the morning of 4 September by John Giffard’s widow, Dorothy, together with George Penderel, ‘a servant of the house’, one of five brothers who worked on the White Ladies and Boscobel estate. They gathered in the hall, and George summoned his elder brother Richard. ‘Mistress Giffard’ gave Charles some sack (dry white wine) and biscuit.

News came that there were 3,000 of his Scottish troops under General Leslie nearby at Tong Castle, but they were in disarray and the Parliamentarians were closing in. Charles feared that if he remained with a group of followers he would be found and captured. He decided to disguise himself as a countryman, initially intending to get to London on foot. The Penderels helped him to change into countryman’s clothes. His hair was cut short, and his face and hands rubbed with soot from the fireplace. Charles’s companions left to join Leslie, while Charles and Richard Penderel remained all day in a nearby wood, Spring Coppice.

Charles changed his plans, and set off on foot with Richard to join Royalist supporters in Wales, but Charles and Richard were unable to cross the river Severn and turned back, finally arriving at Boscobel House early on 6 September. Charles spent the day in the famous Royal Oak, before making his escape to France. While at Boscobel, he heard that Parliamentarian soldiers had arrived at White Ladies the day before, searched the house and torn the panelling down.

After Charles II’s restoration to the throne in 1660, the story of his escape and of White Ladies and Boscobel’s place in it became well known. The Royal Oak is still a popular tourist attraction today.

Read More About Charles II’s EscapeLater History

The White Ladies and Boscobel estate was inherited by John Giffard’s granddaughter Jane, who married Basil Fitzherbert, from another Catholic gentry family. Their main residence was at Swynnerton Hall, near Stone in Staffordshire. White Ladies probably passed out of use as a residence by 1700. At some point in the 18th century the house was demolished, and the ruined priory church became used as a Catholic burial place: Dame Joan Penderel, mother to the five brothers, was buried there. By the time the Reverend Williams, Curate of Uffington and Battlefield, visited the place and painteda watercolour of it, in 1791, the main house had been demolished, though the gatehouse still stood, and was occupied as a labourer’s cottage.

When the Fitzherberts sold the Boscobel and White Ladies estate to Walter Evans in 1812, the immediate site of White Ladies Priory was kept back, presumably because it was in use as a burial place. The last burial there was made in 1844. The priory ruins were placed in the Office of Works’ guardianship by Lord Stafford of Swynnerton in 1938.

The Buildings

The surviving ruins represent most of the shell of the priory church: it was cruciform, about 35 metres long and 8 metres wide, with a five-bay nave, a three-bay chancel and two small transepts, linked to the main space by large arched openings. The walls are of sandstone, in coursed ashlar (square cut stone), and the bays were originally separated by pilaster buttresses. Some fine stonework survives, around the north transept arch, which has scalloped capitals carved with foliage, and around the fine arched doorways in the north and south walls, at the west end of the nave.

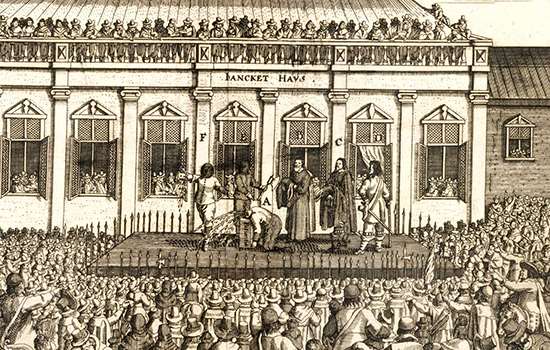

The priory is known to have had a dormitory and refectory. Robert Streater’s famous painting of Boscobel and White Ladies, painted for Charles II in about 1670, shows the shell of the church much as it survives today. Streater shows walls to the south of the church suggesting the shape of a square cloister area, which is shown to be laid out with a formal garden. The view shows a timber-framed wing on the west side of the cloister, probably housing the kitchen and service rooms, which may have been developed from the prioress’s lodgings.

The main house projected westwards from the west end of the ruined nave. A two-storey range apparently housed a great hall (probably one storey high), with a porch and a square bay window at its upper end, and a three-storey cross wing at the far end, which presumably housed the private chambers. Access was via a small, two-storey timber-framed gatehouse, which stood into the 19th century. No trace of the manor house now remains. The priory walls and a small area around them are enclosed by a stone boundary wall, probably dating to the 19th century.

Further Reading

MJ Angold et al, A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2, Religious Houses (London, 1973), 83–4

T Blount, Boscobel, or The History of King Charles’s Most Miraculous Preservation after the Battle of Worcester (London, 1660)

G Wrottesley, ‘The Giffard Family from the Conquest to the Present Time’, Collections for a History of Staffordshire: New Series, Volume 5 (1902)

Explore more

-

Visit White Ladies Priory

Ruins of the late 12th-century church of a small nunnery of ‘white ladies’ or Augustinian canonesses. Charles II hid nearby in 1651, before moving to Boscobel House.

-

Visit Boscobel

Explore the beautiful orchard and gardens, see the descendant of the famous Royal Oak, and hunt out Charles II’s hiding place inside Boscobel House.

-

Charles II and the Royal Oak

Find out how the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War in 1651, giving English history one of its greatest adventure stories.

-

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.