The villa’s development

Great Witcombe was built sometime between the mid-2nd and mid-3rd centuries AD.[1] There may have been an earlier, smaller villa down the slope, where a field survey has identified a rectangular building. This may be the building uncovered by excavations in 1819, which reportedly had abundant wall plaster, but was thought to have been destroyed by the excavation.[2]

The original plan of the main villa was a symmetrical U-shape, carefully terraced into the hillside.[3] The west wing consisted almost entirely of two bath-houses (suites of baths), which were both in use at the same time. The east wing comprised kitchens and storerooms. A rectangular dining room projected from the north side of the central range, which was probably open on one side to provide a covered walkway with a view down the hillside. Both wings had an upper floor where the family lived, and there was probably an upper level above the walkway too. The villa’s entrance may have been straight onto the upper storey.

In the 4th century a series of alterations was made. One of the bath-houses was enlarged and remodelled, and the lower east wing was expanded to create a large barn-like space. Finally, the rectangular dining room was replaced with an octagonal room, which may have had a tower.

Download a plan of the villaDating the villa

There is controversy over exactly when this villa was built. Usually it is fairly easy to date Roman buildings by stratigraphy (the layers in the soil), but when this villa was excavated the stratigraphy was not recorded. Looking at the dates of the finds, Peter Leach, the archaeologist who published a report on the site excavations in 1998, concluded that the villa was probably built in the early 3rd century AD.[4] However, mosaic experts have dated the mosaics stylistically to the late 2nd century AD, in which case the villa must have been built by then.[5]

One possible explanation is that there was an earlier villa – perhaps the one identified on the field survey – which was served by the original lower bath-house, and that the renovations to the baths happened soon after the main villa was begun, about AD 200.

Life at Great Witcombe

The wealthy owners of Great Witcombe may have been involved in politics and administration at the nearby Roman town of Glevum (now Gloucester). This was a common occupation for the rich and powerful of Roman Britain.

The Romano-Britons who lived here may have sought rural peace in choosing this location, but in fact they were well connected. Ermin Way, the Roman road that connected Corinium (now Cirencester) and Glevum, passes less than a mile to the north. Gloucester is only five miles away and Cirencester ten. The villa owners could easily have gone to market in either town and returned the same day.

Many people other than the owners would have lived at Great Witcombe, including slaves who worked on the estate. They would have farmed the fields, looked after the animals and stoked furnaces for the industrial work done here. Finds from the site suggest that metalworking took place on site, including ironworking, lead working and copper-alloy and pewter casting. Down the slope is evidence for much more Roman activity, probably industrial processes associated with the villa.

We know that tiles for the roof and baths were also made here, because wasters – discarded tiles which did not survive the kiln – have been found in the stream.

the mosaics

There were at least three mosaics at Great Witcombe, all in the lower bath-house. Two were relatively simple geometric designs, of which only fragments survive. The most impressive mosaic, however, is the marine mosaic from the frigidarium (cold room) of the baths.

This mosaic depicts a greater variety of sea creatures than any other in Roman Britain. One is an electric ray, which is not seen on any other Roman Britain mosaic.

Local stone and reused tiles were used for the mosaics, but the very small tesserae (tiles) indicate that the work was very expensive, as small tiles take longer to lay and allow for finer detailed work. A master mosaicist probably completed the figures, perhaps working in a workshop or on a trestle table on site. When the mosaicist was happy with the design of the figures, they would have been transferred to the floor. A less skilled worker, perhaps an apprentice, would then have filled in the blank areas of mosaic around each figure.[6]

The mosaics are now housed inside modern buildings on site because they are so fragile. You can see more photographs of them below, together with some objects excavated at the villa.

Religion at the villa

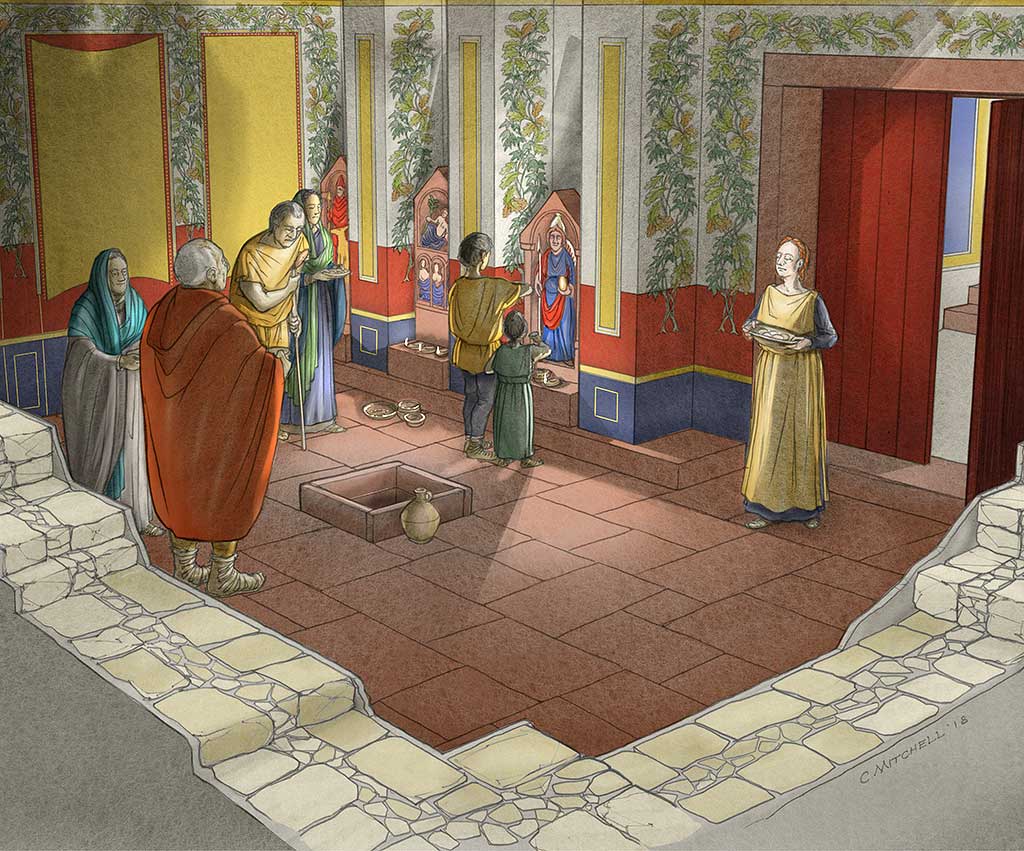

The Romano-Britons thought the world was full of gods. At Great Witcombe there is a mysterious room which would have been partially underground, and may have been used for ritual activities. Its walls were elaborately decorated. Niches in the walls probably held votive statues, to which offerings would have been made. There was a water cistern in the centre which would have been about 30cm deep and was continuously fed by water from natural springs.

We do not know which god or gods were worshipped here. The subterranean nature of the room could mean that it was linked with one of the Roman ‘mystery cults’ – so called because only people initiated into the cults would have known the details of the rituals and beliefs. It has been suggested that the cult was of Mithras, originally a Persian deity, because a terracotta pinecone was found nearby – pinecones are linked with Mithraism. However, a typical mithraeum has a tripartite structure, and the room at Great Witcombe does not – nor does it have any other features typical of a mithraeum. The pinecone may have been just a piece of roof decoration.

Another building nearby, now lost, was probably a nymphaeum, a temple for water nymphs, who were believed to protect natural springs.

Forgery!

In 1966 Ernest Greenfield discovered this piece of carved stone with a fish on it – an early symbol of Christianity. He did not find it in the excavation but on the turf nearby. Could it have been dug up by Lysons and the fish missed all those years?

He contacted RP Wright, an expert on Roman inscriptions, who came to the site to investigate. Using careful detective work about the shape of the stone and the style of the carving, Wright concluded that it was modern, commenting: ‘Some well-wisher with misplaced zeal could have produced this exhibit by using mason’s tools in an amateurish way.’[7]

The end of the villa

Around AD 380, life in the villa changed dramatically. We know this because there are evident changes in building use, including the destruction of some walls so that the stone could be used elsewhere.

The people living at the villa may have moved away, with others coming to live here after a short break. Alternatively, perhaps the owners found themselves in straitened circumstances and could not maintain the same lifestyle. Whatever the reason, the space under the bath-houses for hot air circulation was deliberately filled in, meaning the baths could no longer be heated. This may have been so the rooms could be used to store food.

Things were hard in Roman Britain at this time. Many soldiers stationed there had been taken back to the continent to contend with raiders from beyond the empire. Fewer and fewer coins were being shipped to the island, and almost none after AD 402, causing an economic crisis.[8] Major industries collapsed, so people found it much harder to obtain goods, even if they had the money to buy them. Perhaps Great Witcombe’s former residents left at this time of crisis because the cities with their walls were safer; or perhaps they moved into timber buildings, which were easier to maintain, and used the less stable stone buildings for storage.

Because of the lack of clear dating evidence, it is hard to know how long Great Witcombe remained in occupation. Roman rule in Britain ended around AD 410 and it is unlikely that anyone was still living here after the 5th century AD.

Discovery of the villa

Soil and subsidence gradually buried the villa. It was rediscovered in 1818 by workmen who were removing an old ash tree from a field. The roots brought up a large worked stone which had been resting on two upright stones and proved to be the lintel of a doorway. The landowner, Sir William Hicks, employed Samuel Lysons, a well-known antiquarian, to dig the site, and Lysons uncovered almost the whole plan of the villa.[9]

Lysons reported on his work to the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1818 and 1819. The Hicks-Beech family gave the villa into public ownership in 1919 and in 1938 Elsie Clifford was hired to re-excavate the site. Unfortunately, the outbreak of the Second World War meant she could not complete her work, so in 1960 Ernest Greenfield was hired to continue the job. His 14 seasons of excavation finished in 1973, and his work was published in 1998 by Peter Leach, another archaeologist.

In 2000 English Heritage carried out a field survey of the surrounding area,[10] locating many more Roman features and proving that Great Witcombe was one of the largest Roman villas in Britain.

Further reading

N Holbrook, ‘Great Witcombe Roman Villa, Gloucestershire’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 121 (2003), 179–200

P Leach, Great Witcombe Roman Villa, Gloucestershire: A Report on Excavations by Ernest Greenfield, 1960–1973, BAR British Series 266 (Oxford, 1998)

DS Neal, ‘Witcombe Roman Villa: a reconstruction’, in Ancient Monuments and their Interpretation: Essays Presented to AJ Taylor, ed MR Apted, R Gilyard-Beer and AD Saunders (London, 1977), 27–40

P Witts, Mosaics in Roman Britain: Stories in Stone (Stroud, 2005)

Related content

-

Visit Great Witcombe Roman Villa

Find out how to get there, when the villa is open, and what there is to see in the surrounding area.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of the villa to see how it developed over time.

-

Country estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.