The Draw of the River

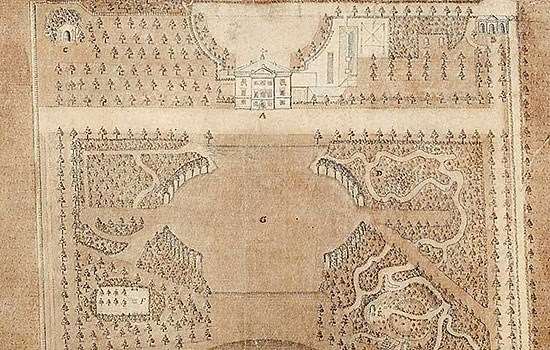

Marble Hill sits prominently on the north-west bank of the River Thames at Twickenham, surrounded by what survives of a carefully designed landscape. However, surviving maps from the 17th and early 18th centuries show that before the house was built, the site was a patchwork of cornfields, meadows, and fruit and kitchen gardens split between multiple owners and farmed by various tenants.[1]

By the 18th century the banks of the river between Hampton Court and Kew were increasingly punctuated by suburban residences built by those seeking to escape the hustle and bustle of London. They were drawn to the area both by its royal connections – it was close to the royal residences at Hampton Court and later at Richmond Lodge – and by its artistic associations. The river had long been a source of inspiration for poets, gardeners and artists.[2]

Henrietta Howard and Marble Hill

In 1723, George, Prince of Wales (later George II) presented Henrietta Howard with £11,500 of stock, as well as jewellery, furniture and furnishings. In order to prevent her husband claiming it the stock was transferred to a trust managed by the Earl of Ilay. This trust provided the financial security for the initial land purchase of 11½ acres at Marble Hill. It included £8,000 capital stock in both the South Sea Company as well as stock and subscription in the Bank of England. The gift of stock came at a time when the South Sea Company was increasing its activity in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans, and dividends it paid to stock-holders included profits from the slave trade. How much of the South Sea Company stock was used to directly finance the land purchase and construction of Marble Hill House is not currently known.

By June 1724 the Earl of Ilay had bought 25½ acres between what is now the Richmond Road and the Thames, and later that year Henrietta started to build her new home, Marble Hill. It was to be a retreat and a product of her hard-won independence. She had survived a turbulent childhood, an abusive first marriage, and 20 years in the royal household as a servant to Princess Caroline (later Queen Caroline) and mistress to Prince George (later George II).[3]

Read more about Henrietta HowardBuilding Marble Hill

To build her new residence, Henrietta drew on the experience and expertise of her vast network of friends and acquaintances.

The builder-architect Roger Morris, who also worked for the royal family, was the builder of the house. We do not know for certain who designed it, but it has been suggested that Morris, the ‘architect earl’ Henry Herbert, 9th Earl of Pembroke, and the leading 18th-century architect Colen Campbell may have played a part in the house’s design.[4] At the same time, the future royal gardener Charles Bridgeman and the poet Alexander Pope – who was creating his own garden just upriver – are known to have worked on the gardens. Henrietta was clearly a well-informed and well-connected patron, and may herself have contributed to the plans.

Marble Hill was at the cutting edge of 18th-century fashion. The house was built in the new Palladian style inspired by the architecture of ancient Rome, as revived by the 16th-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio. It was ideally situated by a flowing river and nestled within an ‘ancient’ setting, which was inspired by the gardens of classical Rome. Together, villa and garden formed a peaceful pastoral refuge from court life.

Read more about the 18th-century LandscapeA Family Home

Henrietta Howard’s first husband died in 1733, and in 1734 she was able to leave the court and the royal ménage à trois and make Marble Hill her main residence. There she embarked on a new and happier phase of her life. She entertained the great and good of 18th-century society and enjoyed family life with her second husband, the MP George Berkeley, whom she married in 1735.

At Marble Hill she and George raised John and Dorothy Hobart, the children of her brother, John, 1st Earl of Buckinghamshire, whose first wife had died in 1727. Later, in 1763, Dorothy’s daughter, Henrietta Hotham (1753–1816), came to live with her. The young Henrietta (who was named after her great-aunt) enjoyed a happy childhood at Marble Hill, entertaining Henrietta Howard’s many guests with impressions and games.

Henrietta made many alterations and improvements to the house and grounds while she was living there. In the 1740s she added an extensive service wing at the east end of the house, and in the 1750s formed a new dining parlour from several small rooms on the west side of the ground floor. Its walls were fashionably adorned with hand-painted Chinese wallpaper, reflecting Henrietta’s passion for ‘chinoiserie’. Her architect in the 1750s was Matthew Brettingham, who had also been employed by Henrietta’s brother, John, at Blickling Hall in Norfolk.

These and other alterations ensured that Marble Hill was up to date and made the house a far more practical and spacious home. Henrietta also expanded her estate, so that by 1752 it was almost exactly the same extent as the current park.

Henrietta’s Heirs

On Henrietta’s death in 1767 her nephew, the politician John Hobart, 2nd Earl of Buckinghamshire (1723–93), inherited Marble Hill. Henrietta’s will stipulated that the house, its contents and the estate were to stay together as ‘Heir Looms’, suggesting her pride in the home she had created.

Having been raised at Marble Hill, the 2nd Earl was familiar with Henrietta’s Thames-side retreat. He leased it out at first, but then lived there from 1772 until his death in 1793.

When the 2nd Earl died without male heirs, Marble Hill passed to his niece, Henrietta Hotham. In spite of her childhood connection to the house, she decided not to live there. Instead she retired to a smaller house in the south-eastern corner of the estate, known as Little Marble Hill or Marble Hill Cottage (which was demolished in about 1873/4).

Tenants at Marble Hill

Henrietta Hotham let Marble Hill to a succession of tenants. Among them was the controversial figure Mrs Fitzherbert who, in a ceremony deemed illegal in British law, had married the Prince of Wales (later George IV) in 1785.

By the time Mrs Fitzherbert left Marble Hill in 1796, it was described as ‘terribly out of repair’.[5] In spite of this, later tenants included the immensely wealthy heiress Henrietta Laura Pulteney (1766–1808), Countess of Bath, and Katherine Powlett (1736–1809), the elderly widow of Henry Powlett, 6th Duke of Bolton.

On Henrietta Hotham’s death in 1816, Marble Hill passed to the 5th Earl of Buckinghamshire (1789–1849), who let the house for a while. His tenants included Charles Augustus Tulk and his family. Tulk was a politician and student of the work of the Swedish philosopher and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. But in 1824 the earl broke the conditions of Henrietta Howard’s will and sold Marble Hill to the resident of ‘Little Marble Hill’, Timothy Brent, an army agent. The following year Brent, in turn, sold Marble Hill to Captain Jonathan Peel (1799–1879).

The Peels at Marble Hill

Jonathan Peel (1799–1879) was a soldier and politician, and brother of Robert Peel, who was twice British prime minister. He was also a well-known devotee of horseracing. After purchasing Marble Hill he immediately built a stable block to the north-west of the house, where he kept racehorses and almost certainly working domestic horses too.[6] Among other changes to the grounds, he also created a fashionable Italianate garden on the 18th-century terracing which had been laid out by Henrietta Howard to the south of the house.

Peel bought Marble Hill shortly after marrying Alice (or Alicia) Kennedy, daughter of the 1st Marquess of Ailsa. They had eight children. Under the Peels’ ownership Marble Hill was not only a family home but once again paid host to those of ‘rank, beauty and genius’ in society.[7] Lady Peel was said to have been one of the best-known hostesses of the mid-19th century – as one newspaper put it, ‘At Marble Hill and in London Lady Alice received statesmen, authors, and diplomatists among her intimate friends.’[8]

Marble Hill’s Last Residents

In spite of this, like the previous owners, the Peels rented out Marble Hill at times. Their tenants included the politician Richard Wellesley, Marquess Wellesley, eldest brother of the 1st Duke of Wellington.[9] The Peels also toyed with the idea of selling Marble Hill, which they put on the market in 1837.[10] However, it would be over 60 years before Marble Hill had a new owner.

In 1887 Lady Peel, by then widowed, died. She was the last resident of Marble Hill. After her death the contents of the house and gardens, the estate, and Marble Hill were put up for auction. After ten years standing empty, Marble Hill was purchased by the Cunards, the famous shipping family, in 1898.

Saving Marble Hill

William Cunard planned to develop the estate, and in 1901 started building roads and sewers, and felling trees. The future of Marble Hill was in jeopardy.

But outcry from local residents at the plans prompted a campaign to save Marble Hill. The house and park, they argued, formed a central and critical part of the famous prospect from Richmond Hill. Their destruction would mark the ‘ruin of the entire view’.[11] A deal was reached with the Cunard family to halt development and in 1902 Marble Hill was purchased with contributions from the London County Council, private donors and local authorities.

Shortly afterwards the Richmond, Ham and Petersham Open Spaces Act was passed, which protected the view from Richmond Hill from any development. It remains the only view protected by an Act of Parliament today.

More about saving the view from Richmond HillMarble Hill in the 20th Century

In 1903 Marble Hill opened as a public park, saved for and by the people.

Across the 20th century the house was adapted and altered to provide visitor facilities. Rooms on the ground floor served as a tea room, kitchen and changing rooms, and those on the first floor as the park-keeper’s flat. The large service wing built by Henrietta Howard to the east of the house was demolished in 1909.

In the 1950s and 1960s campaigns of repair and restoration were carried out and Marble Hill began to take on the character it has today. Work in the 1960s sought to return the house to its appearance in Henrietta Howard’s day, and after completion the house was reopened as a historic house museum by the Greater London Council.

The park also has a long history of varied use. Sports and games such as tug of war, football, rugby, hockey and cricket have all been played in the park since the early 20th century. In the First World War men of the 2nd Battalion Middlesex Volunteer Regiment could be seen parading in the grounds, and in the Second World War allotments sprung up in the south-eastern and south-western sections of the park as part of the Dig for Victory campaign.[12]

In 1986 Marble Hill passed into the care of English Heritage. In 2022 English Heritage completed the Marble Hill Revived project, which has restored the remarkable 18th-century landscape, conserved the historic interiors, improved the facilities in the park and re-interpreted the site.

About the author

Megan Leyland is a senior properties historian at English Heritage with a particular interest in country houses and gender history.

Top image: The Thames near Marble Hill, by Richard Wilson, c.1762

Find out more

-

Henrietta Howard

Though mainly known as the mistress of George II, Henrietta Howard was a remarkable woman in her own right. Read more about her extraordinary life and how she came to build Marble Hill.

-

Henrietta Howard's Garden at Marble Hill

Find out what makes the garden between the house and the river at Marble Hill so significant, and how English Heritage has restored its key elements.

-

The View from Richmond Hill

See how artists have depicted the panoramic view from Richmond Hill over the centuries and find out how Marble Hill was saved thanks to a campaign to preserve this view.

-

Buy the Marble Hill Guidebook

This fully illustrated guidebook includes a tour and full history of the house and grounds, and gives many fascinating glimpses into life at Marble Hill.