Foundation of the priory

The period around 1100 was one of religious revival, which saw several dynamic and reforming monastic orders emerge and many new religious houses founded. One of the most important developments was the rapid expansion of monasteries that followed the Rule of St Augustine, a set of principles attributed to St Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430).

Known as regular canons, the members of these communities were distinct from monks, whose lives were governed by the rather stricter Rule of St Benedict. Unlike monks, Augustinians were generally ordained priests and carried out duties beyond the walls of their priories. They could serve as parish priests or chaplains in rich households and run hospitals. This freedom was reflected in the design of their priory precincts, which were often less heavily enclosed than those of Benedictine orders.

The number of Augustinian priories in England grew rapidly after 1100. Gisborough (also spelled Gisburn or Gisburne) was founded by Robert I de Brus (c.1070–1142). His exceptionally generous gifts of land formed the basis of the priory’s wealth and provided the means to build the priory in stone.

Brus took a close interest in the community, appointing his brother William as its first prior. By the time of the second prior, Cuthbert, who headed the priory from about 1145 to 1154, Gisborough was prominent enough for Cuthbert to be part of the delegation that travelled to Rome to oppose the appointment of William Fitzherbert as Archbishop of York.

The priory prospers

Robert I de Brus died in 1142 and was buried at the priory. His successors continued to support the monastery and used its church – which was rebuilt on an ambitious scale in the late 12th century – as a family mausoleum. Beside the Brus family, Gisborough attracted other aristocratic northern families as patrons, and gained benefactors of more humble social status.

The monastery had roles in the civic life of the town of Guisborough, particularly in education. In the mid-13th century it appointed a master to teach boys from poor families. The boys were probably trained as choristers so that they could assist in the singing of the liturgy.

As a major monastery, Gisborough was also important to the economy of its region. In 1263 Henry III granted it the right to hold a weekly market and an annual three-day fair, which no doubt contributed to its finances. It was rich enough to fund further rebuilding projects in the mid-13th century.

In 1272 Peter de Brus, the last Brus lord of Skelton (the English branch of the family), died without a male heir. Patronage of the priory passed through his sisters to the Thweng and Fauconberg families. Evidence of their inheritance survives in the sculpted heraldry that ornaments the magnificent east end of the church, which was rebuilt after a disastrous fire in 1289.

Fire at the priory

On 16 May 1289 a catastrophic blaze swept through the second priory church. It was recorded in vivid detail by Walter of Guisborough, a canon of the priory at the time.

Walter describes how a plumber and his two assistants were repairing holes in the lead roofs when, ‘with a wicked disposition’, this ‘vile plumber’ placed his iron pans and burning charcoal on the roof’s dry timbers. The three men then went down into the church, abandoning the still-glowing charcoal, which ignited the roof timbers and caused the lead on the roof to melt and pour into the church beneath.

Walter describes how the fire spread, destroying the church together with its furniture and ornaments, the priory’s collection of theological books, and nine valuable chalices, as well as vestments, statues and relics.

Excavations in the 1980s uncovered evidence of the fire damage but also revealed that in fact the destruction was not as severe as Walter’s narrative suggests. It would have been possible to repair parts of the church; however, the canons used the opportunity to rebuild it.

Life at Gisborough

Insights into the religious life of the priory are provided by the records of a visitation – an official inspection carried out by a diocesan bishop – conducted in 1280 by Archbishop Wickwane of York.

Every aspect of life at Gisborough was scrutinised. The archbishop admonished the canons for the poor quality of their chant during church services, for misdemeanours such as leaving the cloister for frivolity and drinking after dark, and for feigning illness so they could be cared for in the infirmary. He also reproached them for their quarrelling and fractiousness.

Visitations, however, by their very nature were intended to find fault, and religious life at Gisborough may not have been in as grim a state as the visitation record suggests. The veneration of local saints flourished: the community observed the feast days of St Hilda, St Cuthbert and St William of York, which are included in an illuminated missal (texts for the Mass) from Gisborough.

The priory in the late middle ages

The early 14th century was a difficult time for Gisborough Priory. Like many other monasteries across northern England, it was badly affected by the conflict between England and Scotland, in which Scotland fought to retain its independence. In 1314, after Edward II’s army was defeated at Bannockburn, the Scots invaded northern England and devastated Gisborough’s estates in the border region. Canons displaced from other Augustinian houses by warfare came to live at Gisborough, undoubtedly putting a strain on the priory’s finances.

To raise money, Gisborough resorted to selling corrodies (lodging, food and board at the priory) to lay people. The canons complained when the Crown imposed retired royal servants on the monastery, whom the canons had to support without payment.

The priory had other sources of income, however – it owned large flocks of sheep, the fleeces of which it sold to merchants as far away as Italy. The canons could also rely on the support of the local landowning elite, and over the course of the 14th century, after the peace between England and Scotland in 1357, the priory recovered.

By 1381 there were 25 canons and two lay brothers at Gisborough, a respectable number for a religious house in the late 14th century. It received many bequests and gifts throughout the 15th century.

The Brus Cenotaph

Perhaps the most impressive survival from the priory is the Brus Monument or Cenotaph, now in the Church of St Nicholas, beside the priory. Dating from the early 16th century, it is likely to have stood prominently in the priory church, and was probably moved soon after the suppression of the priory in 1539.

The monument commemorates King Robert Bruce (Brus) of Scotland (r.1306–29), victor at Bannockburn and the most illustrious descendant of the priory’s founder, Robert I de Brus. The panels on the north and south sides of the monument depict knights of both English and Scottish lines of the Brus family, together with the four Latin Doctors of the Church and the four Evangelists. The panel at the east end depicts the first prior, William de Brus, while the west end panel, now lost, depicted Robert Bruce.

Image: The south face of the Brus Cenotaph

The Suppression

In 1534 the Act of Supremacy declared Henry VIII the supreme head, below God, of the English Church. The monasteries, as institutions that owed loyalty to the papacy, soon attracted his attention. A survey was carried out in 1534 and 1535 to determine the wealth of the monasteries. Gisborough’s annual income made it the fourth richest religious house in Yorkshire.

The priory was visited in 1536 by Richard Layton and Thomas Legh, whose object was to highlight abuses and worldly living in religious institutions so as to discredit them and justify their closure. They accused the prior, James Cockerell, of numerous offences, and forced him to resign. He was replaced by Robert Pursglove, who was considered more compliant with royal wishes.

In 1536 much of northern England rose in a rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace against Henry VIII’s break with the pope. It was in large part motivated by the king’s move to suppress the monasteries. Although Prior Pursglove ensured that his priory was not involved in the rebellion, Cockerell, then retired, backed resistance to the Act of Supremacy. This stance led to his execution the following year.

The suppression of the priory came on 24 December 1539, when the prior and 24 canons signed the deed surrendering their priory to the Crown. Initial plans to turn the buildings into a foundation for priests came to nothing and the site was leased to Thomas Legh. He probably began to destroy the monastery buildings almost immediately.

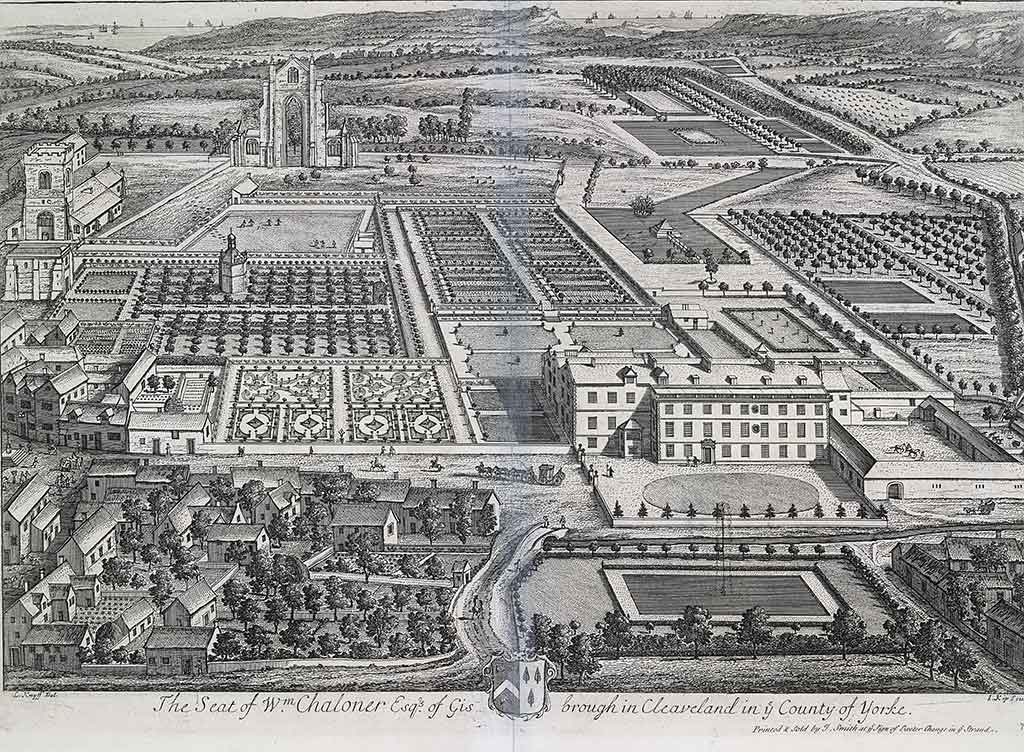

The Chaloners and Gisborough

Thomas Legh died in 1545 and in 1547 the priory was leased to Thomas Chaloner (1521–65), who had begun making arrangements to marry Legh’s widow, Joan, the previous year. In 1550 he bought the site for £998.

A Londoner by birth, Chaloner was a diplomat, courtier, soldier, author and supporter of religious reform. Gisborough was one of many estates he owned and it is unlikely that he spent much time there. It was not until the mid-17th century that the Chaloners established Gisborough as their main seat. They lived first at Park House, west of Guisborough (as the name of the town is spelt), and then in 1680 built Gisborough Old Hall on what is now Bow Street. Neither of these buildings survives.

By 1709 all that remained of the priory buildings was the gatehouse, parts of the west range, and the east end. These were kept as landscape features for the Old Hall, and later integrated in the design of the garden. Fragments of stonework were reused in buildings in and around Guisborough.

The priory rediscovered

In the 18th century the priory began to attract the interest of antiquarians and admirers of the picturesque. It was a member of the Chaloner family, Captain (later Admiral) Thomas Chaloner, who first excavated here in the 1860s. He dug trenches in the east end of the church, searching for the tombs of the founder and other members of the Brus family. By 1867 he had turned his attention to the west end, exposing the remains of the west towers and the western piers of the arcade.[1]

In 1932 the sites of the church, the cloister and the inner court were placed in the care of the Office of Works. Between 1947 and 1954 the west range was excavated and cleared, and in the 1980s the nave and west end of the church were excavated again. A later geophysical survey revealed the presence of other significant remains.

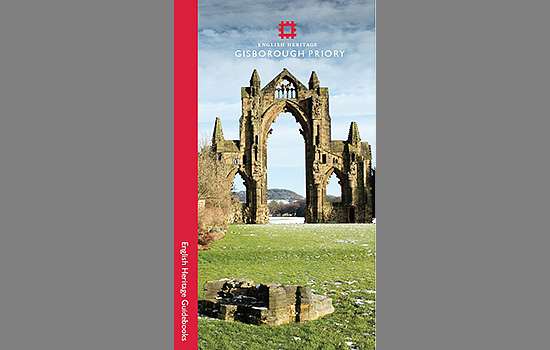

Today the site, which is in the care of English Heritage and managed by the Gisborough Priory Project, remains an impressive testament to the medieval flourishing of monasticism in the north of England.

Further reading

‘Antiquarian discoveries at Guisborough Abbey’, Building News, 14 (18 October 1867), 719

W Brown, ‘The Brus Cenotaph at Guisborough’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 13 (1895), 226–61 (accessed 29 July 2019)

JEB Bruce, ‘An account of recent discoveries at Guisborough Priory, in the North Riding of Yorkshire’, Archaeological Journal, 25 (1868), 247–9

J Burton, The Monastic Order in Yorkshire, 1069–1215 (Cambridge, 1999)

J Burton and K Stöber (eds), The Regular Canons in the British Isles (Turnhout, 2012)

G Coppack and M Carter, Gisborough Priory (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2019)

BJD Harrison and G Dixon (eds), Guisborough before 1900 (Guisborough, 1981)

DH Heslop, ‘Gisborough Priory: Initial excavation of the priory church 1985’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 59 (1987), 175–8 (accessed 29 July 2019)

Related content

-

Visit Gisborough Priory

Dominated by the dramatic skeleton of the church’s east end, the priory remains today give us a tantalising glimpse of Gisborough’s former riches.

-

Gisborough Priory Collection Highlights

-

WHAT BECAME OF THE MONKS AND NUNS AT THE DISSOLUTION?

Discover what happened to the many thousands of monks and nuns whose lives were changed forever when, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England was closed.

-

Buy the guidebook

This fully illustrated guidebook contains a comprehensive history of the priory as well as a complete tour of the impressive remains.

-

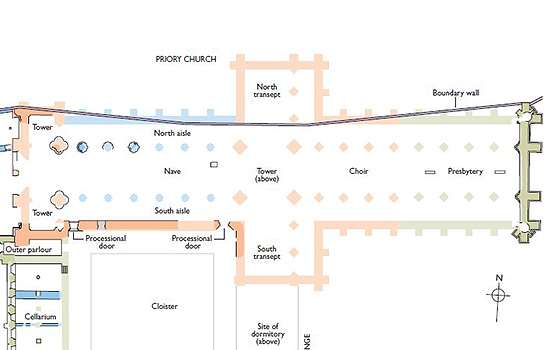

Plan of Gisborough Priory

Download this PDF plan of the priory to explore the priory and see how its buildings developed over time.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.