Godric’s Castle

For many centuries there has been an important crossing point on the river Wye close to where Goodrich Castle stands, creating one of the major routes between England and Wales. This is perhaps one reason why Goodrich was sited here. After the Norman Conquest of 1066, many castles were built along the border.

The history of the castle itself begins soon after the Conquest. We know that an English landowner, Godric Mappeson, had built the first castle here by 1101–2. Nothing now remains of that castle except the name – Godric’s castle became Goodrich Castle.

A generation later another nobleman, Richard ‘Strongbow’ de Clare, started building here too. In 1148 he inherited Goodrich from his father, Gilbert, who had been given the castle by King Stephen about ten years earlier. It was almost certainly Richard who built the well-preserved keep that still forms the core of the castle, and is the only building from this time to have survived. There are several fine architectural details on its exterior.

Richard later achieved fame, or notoriety, as conqueror of Ireland, and also fought for Henry II in Normandy. When he died in 1176 his son and daughter were still children, so his estate reverted to the Crown.

William Marshal

Goodrich remained in royal hands until 1204, when King John awarded it to William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, who had married Isabella, Richard de Clare’s daughter, in 1189.

William rose from relatively humble origins to become one of the most respected soldiers and statesmen in the kingdom, honoured for his loyal support for successive Plantagenet kings. He was also one of the great castle builders of his day. He had already vastly extended and modernised his border castles at Chepstow and Usk, and probably began to update the buildings at Goodrich too around this time. He most likely upgraded its defences, creating new curtain walls and towers in stone.

During the turbulent last years of John’s reign, William remained loyal to the king in the face of rebellion by many English barons, who invited Prince Louis of France to invade southern England. After John’s death in October 1216, William supervised a hasty coronation at Gloucester for the nine-year-old Henry III, knighting the young king himself. The banquet after the ceremony was interrupted by news that Goodrich Castle needed reinforcement against a Welsh attack, which William was forced to repel.

William played a central role in expelling the French in 1217, and served as regent of England until his death in 1219.

The De Valences and the castle

William and Isabella’s five sons inherited Goodrich in turn, but all had died by 1245. In the absence of surviving male heirs the family estate was divided between William’s five daughters and their descendants. In 1247 Goodrich passed to his granddaughter Joan, who in that year married William de Valence, a French nobleman who had recently come over to England. He was also Henry III’s half-brother.

Under William and Joan, Goodrich Castle enjoyed a new period of favour and rebuilding. Documentary and architectural evidence shows that much of what remains of the castle today dates from their time. They made Goodrich one of the most up-to-date castles of its period – an impressive defensive shell concealing residential buildings of extraordinary complexity and architectural sophistication.

William supported Henry III in his power struggle against the English nobility, a struggle that culminated in civil war. Intensely disliked by many English barons as a foreign upstart, he was forced into exile in France and almost lost his English possessions. After the king’s victory he was restored to his estates. In 1270 he accompanied his nephew Prince Edward, later Edward I, on a crusade to the Holy Land and later fought for him in his wars in Wales.

William died in 1296 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Countess Joan and Goodrich Castle

After William de Valence’s death his widow, Countess Joan, kept Goodrich Castle as part of her dower. She spent much time here, often accompanied by her son Aymer and his wife Béatrice.

Unusually, some of Joan’s household accounts survive, and it’s from these that we draw much of the information we have today about Goodrich Castle. The accounts cover two long stays at Goodrich in 1296 and 1297 and provide a rare insight into the personnel and activities of a great castle household at the end of the 13th century. Countess Joan stayed with an entourage of up to 200, entertaining her relations and friends in lavish style.

On Countess Joan’s death in 1307 her son, Aymer de Valence, inherited Goodrich Castle. Like his father, he played an important role in English politics, mostly as a supporter of the monarch, although Edward II (reigned 1307–27) did little to merit his loyalty.

Personal disaster overtook Aymer in 1317 when he was returning from a mission to the Pope in Avignon. A French nobleman captured and imprisoned him, believing Aymer owed him money, and ransomed for the enormous sum of £10,400. The repayments ruined him financially for the remainder of his life.

Read more about Countess Joan’s householdGoodrich and the Talbots

Aymer had no heir, and at his death the lordship of Goodrich passed to his young niece, Elizabeth Comyn. While she was a minor, the castle was again taken into Crown custody. At the time, power at the court of Edward II lay with his latest favourites, the father and son both named Hugh le Despenser. They pressured Elizabeth Comyn to surrender her various possessions to them, kidnapping her and holding her prisoner, until in March 1325 she was forced to release Goodrich to the younger Despenser. But shortly afterwards Elizabeth married Richard Talbot, second Lord Talbot, who in 1326 seized the castle in her name, probably before the Despensers were themselves forced from power.

Goodrich remained a favoured home of Richard Talbot’s descendants for many years. In 1404–5, when Welsh forces invaded the area, the young Gilbert, fifth Lord Talbot, was instrumental in repelling them and securing the castle.

Architectural evidence suggests that some of the visible alterations to Goodrich Castle were made under the Talbots in the 15th century. These include the internal gallery at the west end of the chapel, the extended accommodation for retainers and servants in the east range, and an extra storey above the more prestigious accommodation in the north range, communicating with the chapel.

The Earls of Shrewsbury

During the Wars of the Roses (1455–85) between the rival royal houses of York and Lancaster, successive lords of Goodrich were frequently away fighting. The Talbots forfeited Goodrich after John Talbot, 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury, died in 1460 at the Battle of Northampton, but in November 1485 the 4th Earl finally regained possession of his lands.

By the 16th century Goodrich was used less and less as a residence – the Talbots had larger and more attractive residences elsewhere – although it stayed in use as a judicial centre and prison. George, the 6th Earl, was much occupied with the custody of Mary Queen of Scots between 1569 and 1584, and spent much of his time at Sheffield, his residence in Yorkshire. His second wife, whom he married in 1568, was the wealthy widow Bess of Hardwick. A convenient double marriage linked George’s son Gilbert and daughter Grace to Bess’s daughter Mary and son Henry. Gilbert and Mary moved to Goodrich in 1575, with Gilbert serving as his father's steward.

When Gilbert died in 1616 the castle passed via his and Mary’s daughter Elizabeth to Henry Grey, heir to the earldom of Kent. The Greys let the castle to tenants. A local attorney, Richard Tyler, became constable of Goodrich in 1632 and lived there with his family, carrying out numerous renovations. But in 1643 Goodrich Castle suddenly became caught up in the struggle for control of Herefordshire and the Welsh Marches during the English Civil War, which had broken out in 1642.

Read more about Bess of HardwickGoodrich Castle in the Civil War

Goodrich Castle was apparently initially garrisoned by Parliamentarians, probably with Tyler’s assistance. But it is mainly associated with the Royalist cause. From late 1643 or early 1644 it was occupied by a Royalist garrison under the command of Henry Lingen. The Royalist takeover was evidently violent, with the Royalists burning farm buildings below the castle. By the end of 1645 Goodrich Castle had become the centre of Royalist activity in the area.

On the night of 9–10 March 1646, the local Parliamentarian commander, Colonel John Birch, mounted a surprise attack on the castle stables, stealing the horses and torching the buildings. But this action, though a propaganda coup, had little lasting effect.

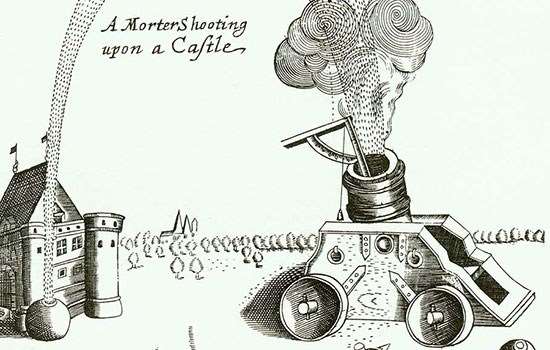

Some three months later Birch returned to Goodrich, this time determined to force Lingen and his garrison into submission. A ferocious siege ensued, the vivid story of which is told in great detail in a number of contemporary letters and later accounts. On 31 July 1646 Lingen’s Royalists surrendered, under threats of undermining and a deadly Parliamentarian mortar (‘Roaring Meg’).

Read more about the siegeAfter the Civil War

The most significant outcome of this episode was the reduction of Goodrich Castle to ruin. However, enough survived for Richard Tyler to move back in. For this reason Parliament ordered that it be ‘slighted’ – rendered indefensible – probably by the removal of the battlements and damage to the main defences. These works were completed in 1648. The castle remained with the earls (later dukes) of Kent until 1755, when it was sold to Admiral Thomas Griffin.

From the 18th century Goodrich Castle took on its latest role, that of a tourist attraction. Like nearby Tintern Abbey, it attained new celebrity as visitors in search of the ‘Picturesque’ were drawn to the Wye valley by its historic monuments and untamed scenery. Lying some 4 miles downstream from Ross-on-Wye, Goodrich made an ideal stopping point for travellers by boat.

By the early 19th century the castle ruins were softened by ivy, wild roses and a famous ash tree in the courtyard. Visiting was a rather hazardous business, with ladders to enable the intrepid to reach the stairs in the keep, while local guides were on hand for historical information. From 1873 still greater numbers travelled along the valley by a new railway line, with a station close to the bridge.

The Castle as Ancient Monument

At the beginning of the 20th century the ruins of Goodrich Castle, though attractively overgrown, were structurally in poor repair. The Office of Works took responsibility for Goodrich in 1920 and over the following decades cleared the vegetation, consolidated the underlying stonework and rebuilt several areas of particularly decayed masonry with stones reused from elsewhere on the site.

These works added greatly to the understanding of the castle’s history, particularly the discovery in 1925 under the south-west tower of the foundations of an earlier tower. Unfortunately, other areas of original masonry that might have revealed more of the castle’s earlier history were hidden by the new repairs.

As the 20th century progressed measures were also taken to improve access around the site, with a new staircase, floors and roofs in the gatehouse and chapel, a modern walkway along the east wall-walk and new stairs and bridges in the keep and south-east tower. Since 1984 English Heritage has been responsible for the conservation and archaeological recording of the castle, and for presenting it to the public.

Find out more

-

Life in a medieval household

Goodrich Castle was a thriving medieval household, where sometimes hundreds of people were living at any one time. Find out about some of the household members and their life at the castle.

-

The Siege of Goodrich Castle

In 1646 Goodrich Castle was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the English Civil War, which Parliament finally won with the aid of a huge mortar, known as Roaring Meg.

-

Life under siege at Goodrich Castle

The 17th-century objects found at Goodrich Castle help us to imagine what life at the castle was like during the Civil War siege. View some of them in detail here.

-

English medieval castles

Once symbols of power and prestige, England’s medieval castles are now monuments to centuries of history. Discover the stories held within their walls.