Discovery and excavation

In 1925, Squadron Leader Gilbert Insall was flying near the Wiltshire village of Durrington when he spotted strange formations in the wheat crop in a field below.[1] The photograph he took that day showed a series of dark spots and concentric rings, as well as several other marks in the same field. The larger site was known at the time as ‘Dough Cover’, and was thought to be a Bronze Age disc barrow. Intrigued, Insall returned the following year and took further photographs.

Excavation of the site was begun in July 1926 by Ben and Maud Cunnington, their nephew Robert Cunnington and a small team of workmen. They spent 15 weeks excavating the site over the next two years, revealing that the dark spots seen on the photograph were postholes, and the rings were a surrounding bank and ditch.

The couple eventually purchased the land and installed painted concrete posts to display the site to visitors. In 1929 a detailed site report was written by Maud Cunnington, who decided to name the site ‘Woodhenge’ because it had so many similarities to nearby Stonehenge.[2]

The Cunnington family

By the time the Cunningtons excavated Woodhenge, the couple had excavated a number of important prehistoric sites in Wiltshire. Ben, a wine merchant by trade, was a descendant of William Cunnington, the famous antiquarian who had excavated many barrows in the Stonehenge landscape in the early 19th century. Ever since, the Cunnington family had been honorary curators of Devizes Museum (today Wiltshire Museum). Ben had held this role since 1887.

The couple’s first joint excavations took place in 1906 when they excavated an early Bronze Age burial at Manton, which Maud wrote up for publication. This established the pattern of their team work. Ben would engage the team of workmen, help to open up the trenches and welcome visitors to site. Maud would decide what should be dug and generally supervised the workmen, and afterwards she would study the pottery and other finds, draw up the records and write the excavation report.[3]

Image: Maud Cunnington, photographed in 1926 (© Wiltshire Museum)

A timber temple

Woodhenge consisted of six concentric rings of timber posts of varying size, forming an oval monument 40 metres (131 feet) long and 36 metres (118 feet) wide. The outermost two rings consisted of relatively small and closely spaced posts. Moving inwards was the ring with the largest posts, comprising 16 posts measuring about 35 centimetres (14 inches) in diameter, each erected using a ramp. Within this ring were three smaller ovals of posts.

Later at least two large sarsen stones were added to the southern side of Woodhenge, placed between pairs of timber posts, perhaps after they had rotted.

Although Maud Cunnington interpreted Woodhenge as an open-air structure, shortly afterwards the archaeologist Stuart Piggott argued that it was a large communal building.[4] His ideas were accepted for many years. However, more recent excavations at The Sanctuary, a similar monument near Avebury, have shown that individual posts were replaced on occasion,[5] indicating that both that monument and Woodhenge are more likely to have been free-standing structures.

Surrounding Woodhenge, and perhaps dug slightly later, were a ditch and external bank, making a henge monument about 90 metres (295 feet) across. A single entrance lay to the north-east. This faced towards Durrington Walls, a large enclosure 70 metres (230 feet) away, where there were other timber structures and a contemporary settlement.

Although we don’t know exactly when Woodhenge was built, it is likely to date from the late Neolithic period, around 2500 BC, roughly the same time that these other monuments were built and the sarsen stones at Stonehenge were being erected.

Offerings

When Woodhenge was first excavated, many objects were found, including Grooved Ware pottery, carved chalk objects, antler picks, animal bones, flint tools, fragments of human bone and at least one human cremation. Rituals that took place at the site included the deliberate placing of objects in the ditch on either side of the entrance, around the posts and into hollows left after the posts had rotted away. Excavations in 1967 across the ditch also uncovered a pile of ten antler picks left behind by those who dug the ditch in the Neolithic period.[6]

At Stonehenge, by contrast, few objects were left behind and the monument seems to have been kept clean. It seems that different forms of ritual and placement of objects were taking place at Woodhenge, perhaps with people processing or moving around the monument in prescribed ways.[7]

Two people were buried at the site – a two- or three-year old child buried near the centre (now marked by a flint cairn) and a young male in the ditch. This burial from the ditch has been dated to between 1760 and 1670 BC, during the early Bronze Age.[8] Sadly the bones of the child appear to have been lost after excavation, but the burial is likely to be of a similar date.

Some of the finds from Woodhenge (pictured below) are on display at the Stonehenge visitor centre, on loan from Wiltshire Museum in Devizes.

A landscape of monuments

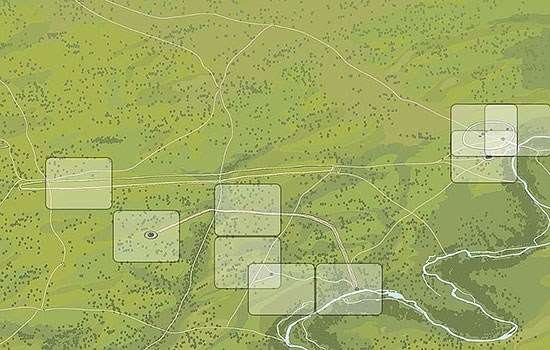

The oval post rings at Woodhenge are aligned north-east to south-west, in the same way as Stonehenge. The horizon towards the south-west, the direction of the midwinter sunset, rises to block any view of the sunset, but to the north-east there is a clear view, so it seems likely that the monument was built to align with the midsummer sunrise.

Another timber monument nearby, the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls, was aligned on the midwinter sunrise. Perhaps these monuments were intended to be used for similar purposes at different times of year, with people processing from here to Stonehenge. We know that the settlement at Durrington was a place where people gathered from long distances for feasting and midwinter celebrations, before the large henge monument was constructed.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE STONEHENGE LANDSCAPEFurther reading

Cunnington, ME, Woodhenge: A Description of the Site as Revealed by Excavations (Devizes, 1929)

Pollard, J, ‘Inscribing space: formal deposition at the later Neolithic monument of Woodhenge, Wiltshire’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 1 (1995), 137–56

Wainwright, GJ and Evans, JG, ‘Woodhenge excavations 1979’, in Mount Pleasant, Dorset: Excavations 1970–1971, ed GJ Wainwright (London, 1979), 71–4

Find out more

-

History of Stonehenge

Read a full history of one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments, from its origins about 5,000 years ago to the 21st century.

-

Explore the Stonehenge Landscape

Use these interactive images to discover what the landscape around Stonehenge has looked like from before the monument was built to the present day.

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.