Research on Hadrian’s Wall

Although Hadrian’s Wall has been studied for over 400 years and excavated for nearly 200, there is still much to be learnt. There are many aspects where our knowledge is inadequate and only a small proportion of the Wall – less than 5% – has been examined archaeologically.

Early Excavation and Research

Scientific survey of the Wall started in the early 18th century, and the remains began to be uncovered about a century later. It was only in 1840 that the whole frontier complex was first attributed to Hadrian.[1]

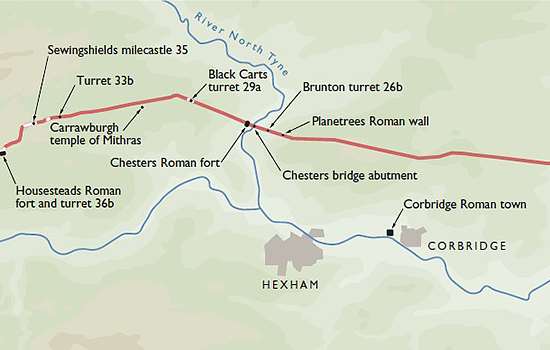

A key figure in the 19th century was John Clayton, who inherited the estate containing Chesters Fort in 1843 and bought other forts and miles of Wall as well as funding excavations. Modern scientific excavation began in the 1890s.

Recent Research

The most important developments of recent years have been:

- the discovery from 1973 onwards of writing tablets at Vindolanda and Carlisle, which provide many insights into life on the Roman frontier [2]

- dendrochronology, which has allowed us to date precisely timbers used in fort construction

- geophysical survey, which has greatly increased our knowledge of the extent of the civilian settlements outside forts

- establishing the direction of planning of the Wall and Vallum.[3]

In addition, re-examination of the remains of the Wall and the reports of earlier work has led to new insights.

Currently there are excavation projects at South Shields, Vindolanda and Maryport. Excavation remains a significant way not only of enhancing existing knowledge but also of discovering completely new features on the Wall, such as the pits recorded on the berm (the space between the Wall and the ditch) over the last two decades.[4] Their discovery has reopened discussion of a particular problem, the function of Hadrian’s Wall.

There is still no published survey of Hadrian’s Wall.

Future Research

Areas that need further research are:[5]

- The Wall’s antecedents: Hadrian’s Wall did not spring complete into existence. It was built in relation to an existing line of forts, fortlets and towers across the Tyne–Solway isthmus, and we need to know more about these.

- The turf sector, that is, the western 30 miles of the Wall, is badly understood. There has been little excavation there since the 1930s, yet what work has been done since has challenged our basic beliefs.

- The Vallum: Excavations across the Vallum have revealed significant contradictions in its construction and use which need to be resolved.

- Civil settlements: Knowledge of the development of forts may be piecemeal, but there has been only one extensive modern excavation of a civil settlement, at Vindolanda. Geophysical surveys have recently demonstrated that there were extensive civil settlements outside the forts along the Wall and on the Cumbrian coast. These have revealed not only buildings, but housing plots, internal and external ditches, and relationships with the landscape beyond. All these, together with cemeteries, are an almost completely unexplored element of Hadrian’s Wall.

Footnotes

1. J Hodgson, A History of Northumberland (Newcastle, 1840), 309.

2. See Vindolanda Tablets Online.

3. J Poulter, The Planning of Roman Roads and Walls in Northern Britain (Stroud, 2010).

4. Bidwell, PT, ‘The system of obstacles on Hadrian's Wall; their extent, date and purpose’, Arbeia Journal, 8 (2005), 53–76.

5. For further discussion see MFA Symonds and DJP Mason (eds), Frontiers of Knowledge: A Research Framework for Hadrian’s Wall (Durham, 2009).