Tudors: Religion

The Tudor era witnessed the most sweeping religious changes in England since the arrival of Christianity, which affected every aspect of national life. The Reformation eventually transformed an entirely Catholic nation into a predominantly Protestant one.

THE OLD ORDER

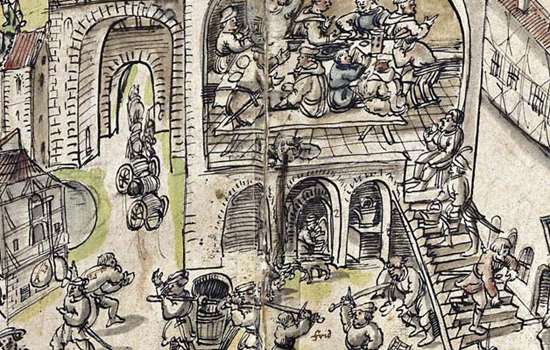

Before Henry VIII’s break with the papacy in the 1530s, the Roman Catholic Church was all powerful in England. Only a small, persecuted minority questioned its doctrines. The early years of Henry’s reign also saw traditional religious practices – such as pilgrimages, saints’ holidays and religious plays – enthusiastically observed, together with the continued building and embellishment of churches that had been a major feature of the reign of his father, Henry VII.

But when Henry declared himself Supreme Head of the Church in England in 1533, following the Pope’s refusal to sanction his divorce from Katherine of Aragon, his decision initiated the Reformation of English religion. With it came the sweeping away of institutions that symbolised medieval Catholicism – and monasteries became the main focus of the king’s attack.

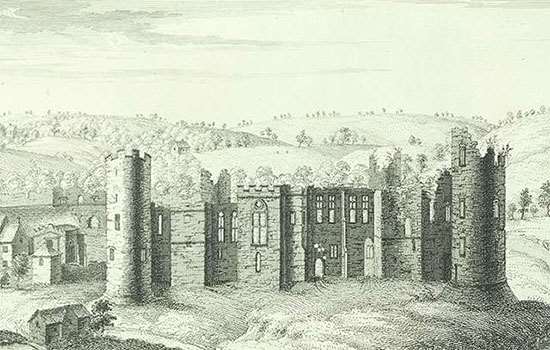

The monastic impulse was long past its peak: excepting those run by stricter orders like the Carthusians, monasteries had become property-owning corporations – some very rich – with few inhabitants. Rievaulx Abbey, North Yorkshire, which had about 650 monks at its peak, had only about 20 by the 1530s; massive Castle Acre Priory, Norfolk, had only ten.

Some smaller abbeys had already closed because of a lack of recruits when Henry VIII forcibly suppressed all monasteries between 1536 and 1540.

REACTION AND ACCELERATION

The Suppression of the Monasteries was largely accepted in the south, especially by those who acquired monastic lands. But in parts of the north it provoked the 1536–7 Pilgrimage of Grace, the largest peacetime revolt in English history.

But although Henry had rejected papal authority, he remained wedded to Catholic doctrine, and burned Protestant ‘heretics’. Real religious change only began to speed up under the radically Protestant Edward VI (r.1547–53), before being reversed when the Catholic Mary I (r.1553–8) tried to restore the old order, burning nearly 300 Protestants in the process.

THE CHURCH TRANSFORMED

For ordinary worshippers, the rapid changes to parish churches between 1538 and 1558 must have been bewildering. Shrines, images of saints and other ‘popish’ trappings were destroyed, removed or (as was the case with the medieval paintings at Binham Priory, Norfolk) whitewashed over.

Under Mary, these were renewed or replaced by royal command, only to be removed again when the Protestant Elizabeth I succeeded in 1558.

The Reformation similarly resulted in striking changes to religious practice – and in time, belief.

The Bible was now accessible to all literate people in English translations. Instead of being spectators at Latin Masses, congregations became participants in English-speaking services that focused on sermon-preaching, Bible readings and set forms of prayer. From 1549 these were formalised in the hugely influential Book of Common Prayer.

THE ELIZABETHAN SETTLEMENT

The present Church of England is effectively the product of the religious compromises promoted by Elizabeth. She declared that she had ‘no desire to make windows into men’s souls’. As long as her subjects remained loyal and publicly orthodox, their private beliefs would not, in theory, be challenged.

Elizabeth’s Church was nevertheless essentially Protestant. Periodic crises of national security led to the persecution of Catholics, particularly after the arrival of the Armada in 1588: Catholics who had been free to worship in private were hunted out, fined, imprisoned or executed. Priest-holes were built in many Catholic homes to provide hiding places.

Yet for some, the settlement did not go far enough to ‘purify’ the old Catholic practices. This confrontation between ‘puritans’ and the official state Church would dominate the Stuart period.

More about Tudor England

-

Tudors: Parks and Gardens

Tudor parks and gardens provided an opportunity for dramatic displays of newly found wealth, success and power.

-

Tudors: Architecture

The architecture of early Tudor England displayed continuity rather than change. Later, however, the great country house came into its own.

-

TUDORS: RELIGION

The Tudor era witnessed the most sweeping religious changes in England since the arrival of Christianity, which affected every aspect of national life.

-

Tudors: War

The Tudor period saw England's medieval army evolve into a larger, firearm-wielding force supported by powerful ships and formidable gun forts.

Tudor stories

-

The Suppression of Roche Abbey

How a vivid eyewitness account reveals the shocking speed and scale of destruction of Roche Abbey after the Suppression of the Monasteries.

-

Walter Hungerford and the 'Buggery Act'

In 1533 Henry VIII’s government introduced the ‘Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie’. Less than ten years later, Walter Hungerford became the first man to be executed under its terms.

-

Lady Anne Clifford

The last member of one of England’s great medieval dynasties, Lady Anne Clifford became something of a legend in her own lifetime.

-

Lydford Law and Parliamentary Privilege

From a Tudor ‘tinner’ to a 21st-century footballer: how the Privilege of Parliament Act can be traced back to the ghastliness of prison life at Lydford Castle in Devon.

-

The Rise and Fall of a Tudor Wool Factory

How the Heydon family of Baconsthorpe Castle in Norfolk made a fortune from the East Anglian wool trade – and then lost it all.

-

Mary Queen of Scots at Carlisle Castle

Find out why, after Mary Queen of Scots fled to England in 1568, her two-month stay at Carlisle Castle began 19 years of captivity.

-

Bess of Hardwick

Rising from a modest background to become one of the richest women of her time, Bess was also a tireless and ambitious builder, whose houses symbolised her rise to wealth and power.

-

Sir Peter Carew and Dartmouth Castle

How a centuries-old stand-off over a castle provoked Tudor soldier and adventurer Sir Peter Carew into trying to outwit the borough of Dartmouth.

-

Lambert Simnel and Piel Island

How a Yorkist claimant to the English throne failed to usurp Henry VII in the final chapter of the Wars of the Roses.