Early occupation

An Iron Age hillfort may have been established here about 400 BC. It was then occupied shortly after the Roman conquest of Britain (AD 43), when it became known as Sorviodunum.

Three Roman roads from the north and east converged outside the east gate of the hillfort, and two sizeable Romano-British settlements were also established outside the ramparts. Little is known of this period, though it has been suggested that in the early Roman period a military fort was set up within the earthworks, with a civilian settlement outside.[1]

The civilian settlement formed the nucleus of one, or both, of the extra-mural Roman settlements. As the need for a fort dwindled, meanwhile, the area within the ramparts was converted to become the precinct for a Romano-British temple.

We have no evidence of the fate of Sorviodunum at the end of the Roman period, and the Anglo-Saxon period as a whole is poorly recorded. In 1003, however, a mint was sited within the old hillfort;[2] and archaeological finds suggest there was late Anglo-Saxon settlement outside the ramparts. So there is evidence of life in and around Old Sarum before the Conquest.[3]

The medieval castle

It is William the Conqueror’s recognition of Old Sarum’s potential shortly after the Conquest that has left the greatest mark on Old Sarum. A motte was thrown up in the centre of the hillfort, creating an inner set of fortifications, with a huge outer bailey wrapped around this inner core.

Not only could this have been done quickly, but the scale of the outer bailey is sufficient to accommodate a large body of troops. Old Sarum’s position on the road network may have recommended the hillfort as an ideal army base in the early stages of the Norman Conquest.

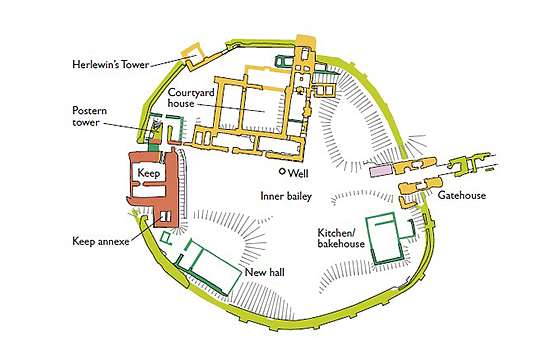

The inner castle became home to a complex of towers, halls and apartments, while the north-western section of the bailey was selected as the site for a new cathedral. Old Sarum's importance as an administrative base grew thereafter, as the sheriffs of Wiltshire were established in the castle and the new cathedral provided a body of literate clerks who are known to have assisted with major projects.

All early buildings in the castle would have been of timber, and the oldest surviving stone structure, the keep, was probably built early in the reign of Henry I (1100–35).

Find out more about the Oath of SarumIn about 1130, however, the castle was made over to Roger, Bishop of Sarum and regent for Henry I during the king’s absences in Normandy.

Roger’s work on the castle is largely undocumented, but although he probably left the major fortifications as they were, the case for attributing a new residence – known as the courtyard house – to him is strong.[4] His downfall and death in 1139 and the subsequent return of the castle to the king brought to an end a period of great ambition at Old Sarum.

The next period of significant building was between 1171 and 1189, when the gatehouse was refurbished, a new drawbridge was constructed, the inner bailey was surrounded by a masonry wall, and a treasury was built in the keep.

At about the same time Henry II was lavishing a colossal amount of money on his great hunting palace at nearby Clarendon, and the work at Old Sarum may reflect a renewed royal interest in its potential. It also coincides with the period between 1173 and 1189 when Henry’s queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, was kept under house arrest at Old Sarum for having incited her sons to rebel against their father.

Read more about Eleanor of Aquitaine

Podcast: The remarkable rise and fall of Old Sarum

Listen to this episode of the English Heriage Podcast to hear English Heritage senior properties historian Steven Brindle and historian John McNeill discuss the history of Old Sarum.

The first and second cathedrals

The cathedral was created after the 1075 Council of London decreed that the see should be moved from Sherborne to Old Sarum. The bishop at the time was Herman, but the major work was completed under his successor, Osmund (1078–99),[5] who shaped the character and constitution of Old Sarum Cathedral.

The first, small cathedral was magnificently extended eastwards by Bishop Roger (1102–39). At his death in 1139 plans to rebuild the nave were abandoned and it was left to Bishop Jocelyn (1142–84) to furnish and fit out the enlarged cathedral, as well as add a new west front.

In addition to the cathedral, a precinct for the cathedral canons and bishop's palace had been created to the north under Osmund and Roger, to which a cloister was added, in all likelihood under Jocelyn.

Abandonment

Dissatisfaction with the site and poor relations with the garrison in the castle caused the cathedral to be moved to its present site in Salisbury (New Sarum) in the 1220s, although royal approval for this move had been given much earlier, in 1194.

A foundation ceremony at the new cathedral was held in 1220 and on 14 June 1226 the tombs of Osmund, Roger and Jocelyn were moved to the new cathedral. This latter event marks the ritual abandonment of Old Sarum Cathedral, after which the demolition of the old cathedral began.

The abandonment of Old Sarum by the clergy during the 1220s marked the end of serious royal interest in the castle. The castle continued in use, however. Over £700 was spent on its repair and maintenance during the reign of Edward III (1327–77), though it is clear that some of the structures in the inner bailey must have been abandoned by then. The courtyard house – identified in 1330 as the building ‘in which the sheriff and his officers dwell’[6] – was the subject of a major overhaul in 1366.[7]

A ‘Rotten borough’

The castle seems to have limped on as an administrative centre into the 15th century, the end finally coming in 1514, when Henry VIII made over the ‘stones called the castle or tower of Old Sarum’[8] to Thomas Compton, together with the right to carry away the materials.

Far less is known about the outer bailey and suburbs. By the time John Leland visited Old Sarum in 1540, even the east suburb was no more: ‘Ther is not one house … [with]in Old Saresbyri or without inhabited.’[9] Old Sarum retained its borough status, however, and despite its lack of population continued to send members to Parliament until the 1832 Reform Act formally disenfranchised such ‘rotten boroughs’.

By John McNeill

Find out more

-

Plan your visit

Climb the mighty Iron Age ramparts for views over the Wiltshire plains and imagine the once thriving castle, cathedral and town of Old Sarum.

-

Postcard from Old Sarum

Take to the skies above Old Sarum to discover this awe-inspiring site and its surrounding landscape.

-

Buy the Old Sarum guidebook

Packed with photos and reconstruction drawings, the guidebook includes a full history and tour of Old Sarum.

-

Download a plan of Old Sarum

Download this pdf plan to see how the buildings of the castle and cathedral developed over time.

-

William the Conqueror and the Oath of Sarum

Find out how William I used the ancient centre of power at Old Sarum to set his seal on the conquest of England.

-

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine was queen of two great medieval European powers – England and France. Read the story of her remarkable life.

-

Podcast: The extraordinary life and times of Eleanor of Aquitaine

Listen to this episode of the English Heritage Podcast to discover the story of one of 12th-century Europe’s richest and most powerful women.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

More resources

-

Why does Old Sarum matter?

Uniquely in southern England, Old Sarum combines evidence for a royal castle and cathedral within a massive Iron Age fortification.

-

Description of Old Sarum

Read about the three main points of interest at Old Sarum – the Iron Age earthworks, the Norman castle and the cathedral remains.

-

Research on Old Sarum

Uncover the latest understanding of Old Sarum, historically and archaeologically, and find out what questions remain unanswered.

-

Sources for Old Sarum

This listing provides a summary of the main sources for our knowledge and understanding of Old Sarum.