Early Life

James Chappell (also Chapple/Chapell/Chappel) is believed to have entered the service of the Hattons in November 1663. Nothing is currently known of how he came to join the Hatton household. However, an undated baptismal record reveals he was in the Hattons’ service by the age of 15. It is possible that the baptism marked the beginning, or early years of his time with the family.

In the register, the clerk records Chappell as a ‘Negro boy of 15, servant to Lord Christopher Hatton’. Adopted from the Spanish, Portuguese and Italian word for black, it is thought that ‘Negro’ was used in England from the 16th century onwards to describe Africans or individuals of African descent. However, it is difficult to determine how consistently the term was used in parish documents, and there are no known records of where Chappell was born.

Life in Service

By the late 17th century black domestic servants had become an established part of the household in many British country estates. Most black male domestic servants in the 17th and 18th centuries probably occupied visible roles, such as a pageboy or footman. They were seen as symbols of their master’s status, wealth and overseas connections.

Some may have been transported to Britain by aristocrats returning from continental Europe, where the slave trade had been established earlier – particularly Holland and France – or from the Caribbean and North America by plantation owners or ship captains, among others. This was also a period when Britain was intensifying its involvement with the transatlantic slave trade. The same year that Chappell is believed to have entered the service of the Hattons, Charles II issued a charter giving the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa a monopoly in transporting people from the west coast of Africa to the English colonies in America. This marked England’s official, royally approved, participation in a trade Britain would come to dominate.

Yet although slavery was established in the colonies, when Chappell was in service the institution of slavery was not defined or established on English soil. The status of black domestic servants could therefore be ambiguous and varied between families. Some were paid wages or in kind, and could leave their employment by choice. However, others were treated as slaves. They were unpaid and unable to leave of their own free will. It can often be difficult to establish how individuals were treated or how their status was perceived, with many only being described as ‘servant’.

The conditions under which Chappell worked and his exact role in the Hatton household are not known. However, it is possible to make some suggestions from the few records which survive.

His movements seem to reflect those of Christopher Hatton, 1st Viscount Hatton. Hatton travelled between London, his Northamptonshire home, Kirby Hall, and – after he became governor of Guernsey in 1670 – Castle Cornet on Guernsey. In his own 18th-century account, Chappell recounted how he ‘putt his said Lord to bed’, so it is tempting to suggest that Chappell was a personal attendant to Christopher Hatton, such as a groom of the chamber, and travelled with him between his various residences.

That Chappell spent time at Kirby Hall is suggested in a chance reference in a letter from the late 1660s or early 1670s. Lady Cicely Hatton, the first wife of Christopher Hatton, added a note at the end of a letter to her husband:

I Desire that you will ask Blak James for the key of his chamber Door wher John wormstall lay for it cannot be found James must be trying wether it would open the seller and pantrey

‘Blak James’ almost certainly refers to James Chappell. With access to household keys and possibly his own chamber, Chappell is likely to have been a trusted member of the Hatton household.

A Heroic Rescue

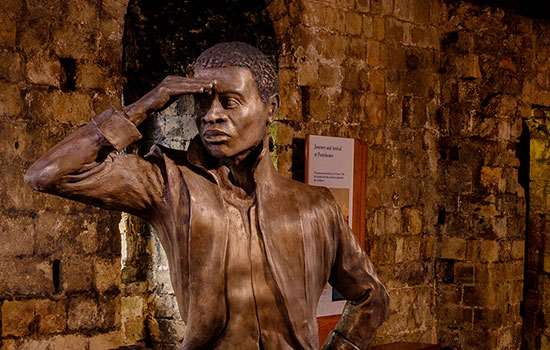

The extent of Chappell’s presence in the historical record is probably in no small part the result of his actions on a stormy night in December 1672, when Chappell led the rescue of Christopher Hatton and his family from the rubble of Castle Cornet on Guernsey. Chappell would recount this night over 50 years later in 1727, aged about 82. His ‘deposition’ of events was recorded by Joshua Lankart and published in the 19th century. The tragic events Chappell described reveal his heroic actions and the devastation which the explosion wrought on the castle and Hatton family.

The huge explosion, which destroyed much of Castle Cornet, was caused when the gunpowder magazine was struck by lightning. After being woken by another servant, Chappell heard his master calling for help and went to his aid. He ‘crep’t on his hands and knees’ through the wreckage onto the castle wall, where he discovered Lord Hatton, wearing only his nightshirt, still on his ‘mattress and feather-bed’ and with his ‘bed-clothes over him’. Chappell carried Hatton on his back down from the wall and to the safety of the guardroom.

He then led the search to find Hatton’s wife, Cicely, and their children. Around where he thought Lady Hatton should be in the building, he heard a noise: ‘I hear something under me; so pray, digg here, and see if it is not my lady’ he told the captain of the garrison. There they found Anne Hatton, then around three years old. Further into the wreckage were Margaret Hatton (about a year and a half) and Elizabeth Hatton (only about three weeks old). Margaret was found cradled in the arms of her nurse, who lost her own life. Among the others who died were Christopher Hatton’s mother, Elizabeth, and wife, Cicely, who had still been lying in after the birth of her daughter.

In an entry in his prayer book for 1672, Lord Hatton describes his thanks:

For that great & almost miraculous preservation of my self & Deare Daughter from an iminent danger by the blowing up of Gunpowder when thou were pleased to take to my selfe my pious mother & Deare wife the Comfort of whose society while shee lived with me I must ever acknowledge with thankfulness.

Cicely’s grandmother Lady Anne Clifford also wrote of her ‘great grief and sorrow’ at the death of her grandchild and of ‘God’s mercifull providence’ at the survival of her three great-grandchildren and their father. The bodies of Cicely and Elizabeth were brought back to England and interred in Westminster Abbey on 11 January. The three daughters who Chappell had helped rescue from the explosion travelled from Guernsey in June 1673 to London, where they stayed with their grandmother at Thanet House. Sadly both Margaret and Elizabeth Hatton (the Hattons’ second and third daughters) died at Kirby Hall in about 1674.

‘A Tale of Castle Cornet’

The events on Guernsey became enshrined in family legend and were published in a number of 18th- and 19th-century books and periodicals. This included a ballad written in 1872 by George James Finch-Hatton, 11th Earl of Winchilsea, and inspired by Chappell’s account of events recorded nearly 150 years previously.

Finch-Hatton inherited Kirby Hall in 1858 and was a descendant of Anne Hatton (later Finch), one of the children pulled from the rubble. Entitled ‘Lord Hatton: A Tale of Castle Cornet in Guernsey’, his ballad begins with a prophecy from a ‘weird woman’ given to Hatton (otherwise known as Kit) when riding through Rockingham Forest to Kirby Hall: ‘Kit Hatton! Kit Hatton!/ I rede ye beware/ Of the flash from the cloud/ And the flight through the air!’ This was a warning of the explosion to come. Finch-Hatton’s poetical account also includes the rescue of Hatton by Chappell:

Then James Chapple, the Negro,

So proper and tall,

On his hands and his knees

Brought his lord off the wall,

Safe into the guard-room,

Free from danger and harm;

For the garrison now

Had got up the alarm…

Hatton concludes the ballad with the thought that, had a beam fallen on Anne Hatton or had she not possessed ‘One more life than a cat’, then ‘This marvellous lay / Of the gallant Lord Hatton / Had never seen day’. However, it is clear that Anne owed her survival not only to luck but to the bravery of Chappell, who without hesitation went to the aid of the Hattons.

Family Life

After the explosion Chappell appears to have returned to Northamptonshire and settled in Gretton, just over 3 miles from Kirby Hall. Records of his personal and family life are fragmentary, but it seems that he married twice and had children. Parish records for St Martin’s, Westminster, believed to relate to Chappell, record the marriage of a ‘Jacobi Chappell’ to ‘Elizabethae chappell’ in 1672, before the explosion. The couple are later found in parish records for Gretton, where the baptism and death of their daughter and, in 1704, the death of ‘Elizabeth Chappel’ are recorded. Chappell is thought to have married Mercy Peach on 7 May 1705 and had two children with her, one of whom died soon after birth.

Chappell may have continued in service after his return from Guernsey. In Christopher Hatton’s will, written in 1695, he is described as ‘my servant’. Although some employers at this time were wary of servants marrying, there were married servants who continued to work in service.

Hatton’s will also suggests that he did not forget Chappell’s role in the events on Guernsey. Chappell was to receive £20 a year during his lifetime: ‘And to my servant James Chapell I give one annuity of twenty pounds a year during the term of his life.’ This was a significant sum, amounting to around 222 days’ wages for a skilled tradesman at the time, and was significantly more than the sums given to other servants, who received a year’s wages above what was owed to them.

After Hatton died in 1705, Chappell and his second wife would have been able to live comfortably. Perhaps this was an act of gratitude for Chappell’s service, but also for his part in that dramatic episode in Guernsey.

Pub landlord and local legacy

Chappell’s role on Guernsey and his life were recorded not only by descendants of the Hatton family, but also by the local community he was part of. Local folklore recounts that Chappell became the landlord of the local pub, the Hatton Arms. Although there is no known evidence to confirm this, there was a family connection. A record of the licensees of the Hatton Arms includes Thomas and Anna Peach, who were landlords in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Although Chappell is not himself listed, it is thought that Thomas and Anna were related to his second wife, Mercy.

These limited but insightful records of James Chappell’s life offer a rare glimpse into black British history. As Terry Bracher, former chair of the Northamptonshire Black History Association, writes, ‘James Chappel is an outstanding example not only of the hitherto hidden contribution of Black people to British history, but also of the way in which Black people have a long tradition of integrating into local communities.’ Although few details of Chappell’s life can be established with a great degree of certainty, his heroic involvement in the events on Guernsey has ensured that, unlike many domestic servants, he has been remembered by history – by the descendants of the man he rescued as well as by the local community he was part of.

Related content

British Library, ‘Charter granted to the Company of Royal Adventurers of England Relating to Trade in Africa’, Discovering Literature: Restoration & 18th century collection items (accessed 4 June 2021).

T Bracher, ‘The Early Presence’ in Northamptonshire Black History Association, Sharing the Past: Northamptonshire Black History (Northampton, 2008), 3–10

K Chater, Untold Histories: Black people in England and Wales during the period of the British slave trade, c. 1660–1870 (Manchester, 2009)

GJ Finch-Hatton, 11th Earl of Winchilsea, ‘Lord Hatton: A Tale of Castle Cornet in Guernsey’, Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine, 690:113 (April 1673), 476–83

JP Gilson (ed.), Lives of Lady Anne Clifford Countess of Dorset, Pembroke and Montgomery (1590–1676): Summarized by Herself (1916)

IH Habib, Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500–1677: Imprints of the Invisible (Aldershot, 2008)

M Kaufmann, Black Tudors: The Untold Story (London, 2017)

J Musson, Up and Down Stairs: The History of the Country House Servant (London, 2009)

Northamptonshire Black History Association research database (accessed 4 June 2021)

O Nubia, Blackmoores: Africans in Tudor England, Their Presence Status and Origins (London, 2013)

D Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History (London, 2016)

RC Richardson, Household Servants in Early Modern England (Manchester, 2010)

-

The Heroic Servant of Kirby Hall

In this episode of our Speaking with Shadows podcast, Josie Long heads to Kirby Hall on the trail of James Chappell.

-

History of Kirby Hall

Read more about the history of Kirby Hall, the magnificent Northamptonshire mansion where James Chappell was a servant to the Hatton family.

-

Black history

Black history is a key part of England’s story, reaching back many centuries, and helps us to reflect on the connections between past and present.

-

Black Lives in 18th-Century Britain

We take a look at the lives of black people – including soldiers, servants and independent citizens – who lived under the shadow of slavery in 18th-century Britain.