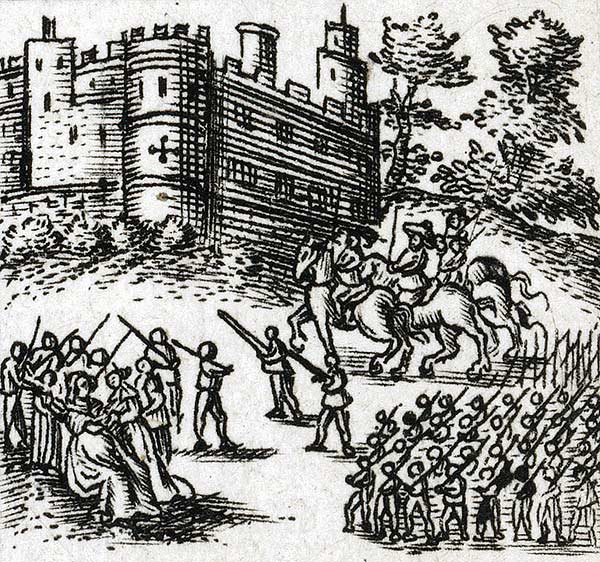

THE SIEGE DAY BY DAY

Tuesday 2 May 1643

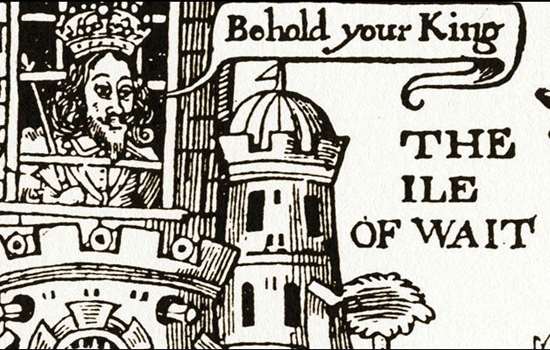

Sir Edward Hungerford’s Parliamentarian forces arrive at Wardour and demand that Lady Blanche hand over the castle. She refuses, saying she ‘had a command from her lord to keep it, and she would obey his command’. Hungerford calls for reinforcements.

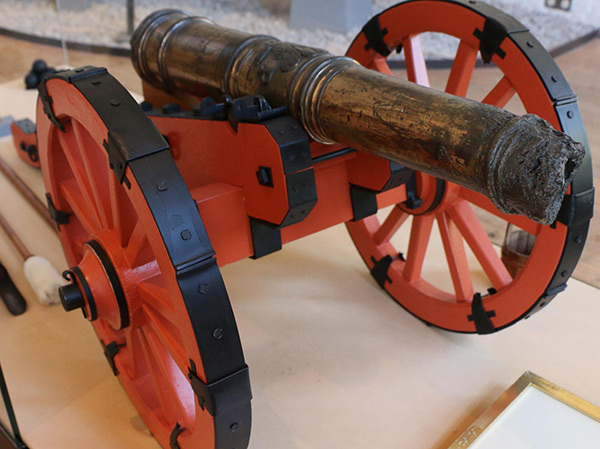

© Royal Armouries

Wednesday 3 May

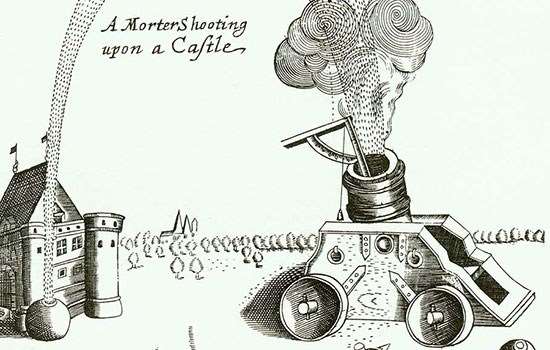

Two small Parliamentarian field guns arrive and are probably placed on the hill to the north-east of the castle (shot damage can still be seen on the castle’s north-east façade).

The besiegers set up their temporary base, perhaps in and around the stables east of the castle. To provide more cover from Royalist fire, they dig earthworks such as trenches to protect the foot soldiers and parapets for the field guns.

The Parliamentarians offer to spare the lives of Lady Blanche, her daughter-in-law, the children and maids, but not the lives of the fighting men. Blanche and Cicely refuse, choosing ‘bravely … rather to die together than live on so dishonourable terms’.

Later that week

The light artillery fire has little impact on the castle walls, although one shot smashes through a window and damages an elaborate fireplace. The besiegers place gunpowder at the end of an old tunnel leading to the castle from the south-east. Again, the explosion causes little damage.

The Parliamentarians then mine towards another part of the castle, probably branching off from the passage to reach a latrine shaft on the south side. They place two or three barrels of gunpowder here. When they set off the charge, an explosion passes up through the shaft, which ‘did much shake and endanger the whole fabrick’ of the castle.

As the days pass the besieged male servants and soldiers tire, ‘distracted between hunger and want of rest’. Lady Blanche orders the maids to take charge of reloading the defenders’ guns with powder and bullets.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Monday 8 May

The Parliamentarians place another gunpowder charge – either (according to the Royalist account) attached to the ‘garden-door’ of the castle (probably the smaller door on the north side) or (according to Edmund Ludlow) by another latrine shaft, perhaps on the castle’s north-west side.

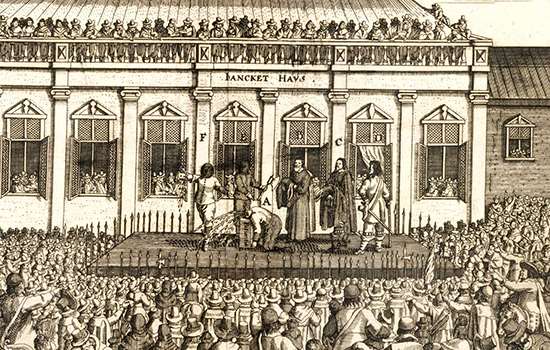

© Folger Shakespeare Library

They set an hourglass in motion and threaten to set off the gunpowder charge after one hour. This touch of drama has the desired effect: Lady Blanche asks for talks.

Lady Blanche and the besiegers agree to three articles of surrender. All the men and women are to be spared, the women can leave the castle and be supported by six male servants, and all furniture and goods in the castle are ‘to be safe from plunder’.

Lady Blanche and her household surrender.

Monday 8 or Tuesday 9 May

Captain Edmund Ludlow arrives to take charge of the captured castle.