Richborough’s Arch

Today, Richborough lies a couple of miles away from the coast, but 1,900 years ago the coastline was quite different. The Roman town lay at the southern end of the Wantsum Channel, a sea passage between the mainland and Thanet, which was then an island. A large shingle bank partially obstructed the exit of the Wantsum into the North Sea, creating a convenient natural harbour behind it at Richborough, where ships crossing between Britain and Gaul (France), or heading into the Thames, could safely anchor.

The Romans fortified this anchorage for the fleet during their invasion of Britain in AD 43. Rutupiae soon developed into a major port and remained a town for the next 350 years, until the very end of Roman Britain.

In around AD 90 the Romans built a monumental arch, a towering 26 metres high, overlooking the shore. Ships landing at the port or passing by would have seen it from miles away, and for many travellers across the English Channel it was their first sight of Britain. A major Roman road, known today as Watling Street, started at the foot of the arch and proceeded to the provincial capital, Londinium (London), and across the Midlands to Wroxeter in Shropshire, about 250 miles from Richborough.

For the next 200 years, the arch presided over a thriving port.

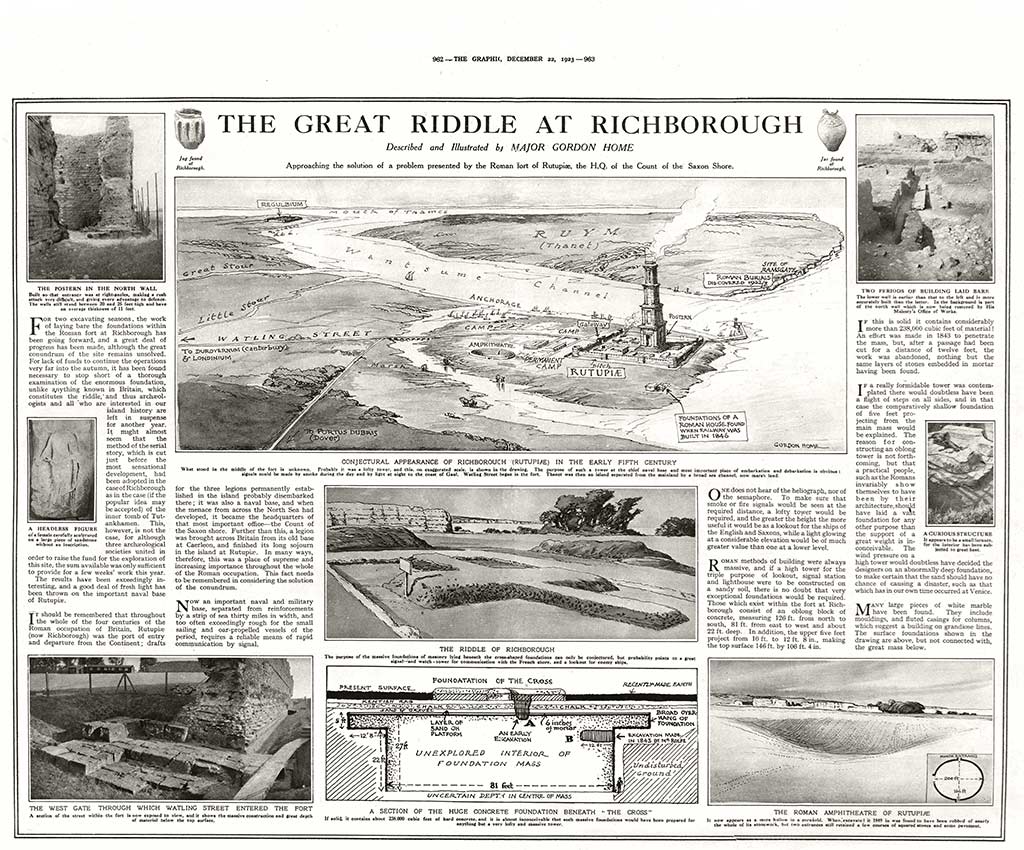

This artist’s impression shows Richborough’s arch, which stood on a huge foundation. The inscription across the top of the arch is unknown, but this image gives an indication of its style

© English Heritage Trust (illustration by Simon Edwards)

What did it look like?

Richborough’s arch was a quadrifons – a particularly rare and elaborate type of arch with four faces and four openings. A raised cruciform (cross-shaped) pavement, accessed by steps, ran beneath the archways. At around 20,000 tonnes, the arch required underpinning by a 9-metre deep stone foundation.

The arch was both a testament to the brilliance of Roman engineering and a beautiful work of art. Each opening and corner was decorated with carved columns and pilasters. It was adorned with mouldings and carried at least one inscription (an account of who built it and why). There was probably a large statue on top and possibly further carvings and inscriptions elsewhere. Even the pavement and the top of the foundation were paved with marble.

While the basic design of the arch is well understood, only fragments of its decoration survive. This makes it difficult to be sure which parts of the decoration went where, what was inscribed on the arch, and who or what was depicted.

But the arch was certainly striking, not least because it was clad in bright white Carrara marble. This exclusive and expensive stone was quarried in Italy and could only be used with permission from the emperor himself. Given this, and the high technical complexity of building and decorating such a structure, it’s likely that specialist masons came to Britain to build it.

Which emperor?

In Roman society, power and status were expressed through sponsorship in the construction of public monuments. Roman emperors often used arches to mark their achievements, especially conquests. They would incorporate their names and a record of their success as part of the decoration, both in writing and in sculpture.

Only an emperor could commission a monument as prestigious and ambitious as Richborough’s arch. But since just a few meagre pieces of its dedicatory inscription survive, it’s impossible to be sure which one.

Analysis based on excavations in the 1920s and 1930s suggested that the arch was likely to have been built during the reign of Domitian (AD 81–96). He had conducted lengthy campaigns in Britain while attempting to complete the conquest of the whole island. When his army defeated the Caledonians at the battle of Mons Graupius in AD 83, the end was in sight. So an arch at Richborough would have been a fitting monument to the culmination of the conquest of Britain.

But recent analysis of the surviving fragments of the arch’s marble decoration has revealed that the arch could have been completed at any time between AD 90 and 150. This was a period during which various emperors, such as Trajan and Hadrian, were prolific sponsors of public buildings and monuments across the empire.

As we are unlikely to discover new evidence, we may never know for sure who commissioned the arch.

Symbolism and function

The arch’s format and position just above the shore suggest that it symbolised more than one specific event or person. The Romans often used arches to mark important boundaries, such the entrance to a city, or even the gateway to an entire province. While other British ports, such as Dubris (Dover), welcomed trade crossing the English Channel, Roman sources record Richborough as the principal port of Roman Britain. There are various Roman accounts of important officials crossing from Gesoriacum (Boulogne) to Richborough before heading towards London, Britain’s largest city.

The decision to build a quadrifons arch is significant, if mysterious. Quadrifonic arches, because of their four openings, had a crossroads at their centre, and often stood at important intersections. As well as marking Richborough as the official entrance to Britannia, perhaps two of the openings also symbolised the point of transition between sea and land – although it’s unclear what the other two openings pointed to.

But whatever its symbolic purpose, the arch had a practical function. Its size, location and bright white colour meant it could be seen for miles out to sea. This gave ships a recognisable landmark by which to navigate and locate Richborough’s harbour.

The remains of the arch consist of the foundation – the top of which is covered by a gravel surface – and a raised, cross-shaped platform which was once the pavement that ran beneath the four archways

Richborough’s ‘Great Riddle’

The mystery of Richborough’s arch was only unravelled after centuries of exploration and research.

By the 16th century, Richborough’s Roman story had been long forgotten. But as interest in the ancient past grew, visitors started to explore places like Richborough in search of clues about the history of ancient Britain. They were confronted by the imposing walls of the later shore fort, but the only visible remains of the town were the arch’s foundation and a cruciform pavement on top – the remains of the crossroads beneath the arch. The Tudor antiquarian John Leland describes exploring the mysterious remains, entering a ‘cave’ under the foundation by candlelight.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that archaeologists systematically explored the mysterious mass of masonry, striving to figure out what it was. In 1843, a Mr Rolfe sunk various shafts around the foundation before trying to force an entrance into what he presumed was a sunken chamber. His workmen spent two weeks laboriously digging 16 feet (5 metres) into solid masonry before giving up.

Later, the Kent Archaeological Society excavated and decided that there were no entrances, that the ‘chamber’ was a foundation and that the cruciform platform was the base of a structure of some kind.

One of various hypotheses about the building’s purpose was that it was an elaborate version of a pharos, or Roman lighthouse, one of which still stands at Dover just to the south. Another was that it was a signalling tower with multiple open-fronted compartments, into which lights could be placed to spell out complex messages to ships at sea. Perhaps most ingenious was the idea that the foundation was a fulcrum for a capstan to draw ships up from the harbour onto land, to protect them from attack, and that the cruciform platform was evidence of a later Saxon church.

It wasn’t until comprehensive excavations took place in the 1920s and 1930s that evidence was finally available to work out what the foundation and platform really were. A team led by JP Bushe Fox excavated the structure and its surrounds, made precise measurements and unearthed thousands of fragments of stone. Their work demonstrated that the foundation once supported a massive marble-clad structure.

The idea that it was an arch was proposed in the 1950s. In 1968, Barry Cunliffe suggested that it was a four-way arch, and that the cruciform platform was the remains of two roads that met beneath it, rather than the base of the structure itself. Painstaking analysis of the stone fragments by Gerald Strong determined its height of 86 feet (26 metres) and its overall design.

Later use

The arch stood at the heart of the town for almost 200 years. But around AD 250 the Roman army moved back to Richborough. Part of the town around the arch was demolished and replaced with a small fort. The arch may have been repurposed as a watchtower. In any event, it sat within the fort, protected by three ditches, a rampart and a palisade.

Then after around AD 275 a large stone fort was built at Richborough. This was probably done by a military commander, Carausius, when he and his successor, Allectus, made Britain and Gaul independent of the Roman Empire.

To make way for the stone fort more of the town had to be demolished, including the arch. Most of its marble decoration was burned to make lime, reused in the mortar of the fort’s walls. But even without its arch, Richborough remained a port town and the gateway to Britannia. Roman historians record important people passing through right up until the end of Roman rule.

We don’t know what happened to the settlement after the army withdrew in about AD 410. By the late 14th century, Richborough had become a small settlement beside the river Stour, playing a role in trade around the prosperous port of Sandwich, downriver. The east wall of the fort had collapsed and was used as a quayside.

The arch today

Visitors to Richborough today can explore the remains of over 400 years of life at the settlement. Still prominent at the centre of the site is the raised cruciform pavement that once ran beneath the arch.

At first sight, it’s easy to assume, as generations of archaeologists once did, that the platform is the base of a cruciform building. But it was in the spaces between each pair of arms that the massive piers of the arch once stood, at the four corners. These supported the four openings that spanned each arm of the pavement and held up the heavy masonry above.

The top of the arch’s foundation stretches out well beyond the pavement, at 44 by 32 metres, its size a testament to the awesome weight of the superstructure. The top of the arch would have been two and a half times higher than the walls of the stone fort as they stand today, and almost three times the height of the modern replica gateway nearby.

Although the stone walls and replica gate have a more tangible and imposing presence today, the long-absent arch once defined what Richborough meant to Roman Britain.

Find out more

-

VISIT RICHBOROUGH ROMAN FORT AND AMPHITHEATRE

Richborough is perhaps the most symbolically important of all Roman sites in Britain, witnessing both the beginning and end of Roman rule.

-

HISTORY OF RICHBOROUGH ROMAN FORT AND AMPHITHEATRE

Read a full history of this key site, which witnessed over 360 years of Roman rule – the entire length of the Roman occupation of Britain.

-

THE ROMAN INVASION OF BRITAIN

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched an invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

THE RICHBOROUGH AMPHITHEATRE: DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION

Excavations of Richborough’s Roman amphitheatre in 2021 produced some revolutionary results. Find out what the archaeologists discovered.

-

RECREATING A ROMAN GATE AT RICHBOROUGH

Find out how English Heritage has gone about recreating a Roman gate and rampart to reflect what the original gateway would have looked like.

-

Richborough and the Roman World

Explore a map of the Roman Empire to find out where some of the objects found at Richborough came from, and how they got to Richborough.