Past Lives: Sir Walter Scott at Conisbrough Castle

Following the 200th anniversary of the publication of Ivanhoe, we reveal the role of this romantic fortress in Sir Walter Scott’s historical novel.

‘There are few more beautiful or striking scenes in England than are presented by the vicinity of this ancient Saxon fortress.’

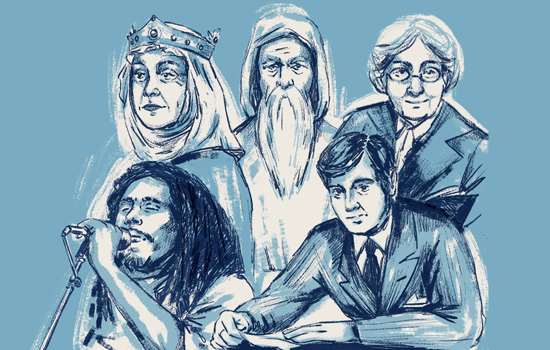

Ivanhoe is the story of a dispossessed knight who, through the offices of a just king, is able to marry his love. Outside of the romance of this marvellous tale, Scottish writer Walter Scott’s phenomenally popular medieval yarn is also a story about the creation of a ‘British’ identity, and reveals much about important political and intellectual debates of the day. The birth of this identity was situated in an ‘ancient’ seat of kings, Conisbrough Castle in South Yorkshire.

In a letter to a friend in 1811, Scott recalled glimpses of Conisbrough Castle he had seen in transit: ‘I once flew past it in the mail coach, when its round towers and flying buttresses had a most romantic effect in the morning dawn.’

Thus captivated, he embellished Conisbrough with ancient origins developed from his accurate interpretation of the origins of its Old English name Cyningesburh (‘the fort of the king’). In Ivanhoe, ‘Coningsburgh’ is the ancient seat of kings where leaders of the two ‘races’ of the kingdom – the educated but aloof Normans and resourceful but backward-looking Saxons – met to be reconciled by Richard the Lionheart. Though the castle is not as old as Scott imagined, the venue he chose to unite the groups, to forge a new English identity, was understood as a castle from a lost golden age.

The motif of unity was clear: Scott wanted to stress the potential of a newly forged British identity out of the constituent peoples of the country in the aftermath of recent civil violence, at Peterloo in 1819, and the more distant Jacobite uprising of 1745. Ivanhoe, published in the same year as Peterloo, was in part Scott’s own appeal to a golden age of democracy and unity.

This was also a time when intellectuals sought to explain social position and morality as products of physical or biological characteristics – racialism.

The identification of the Saxon ‘race’ in England and parts of Scotland, in contrast to Gaels and Jews, underpinned how intellectuals such as Scott understood their past, in contrast to the other ‘race’ communities of 19th-century Britain.

The union of ‘races’ in Ivanhoe is a significant reason why Scott’s story remained so important in school curriculums across the British Empire in the 19th century.

Words by Will Wyeth

Illustration by Nick Hayes