GARTHWAITE, Anna Maria (1690–1763)

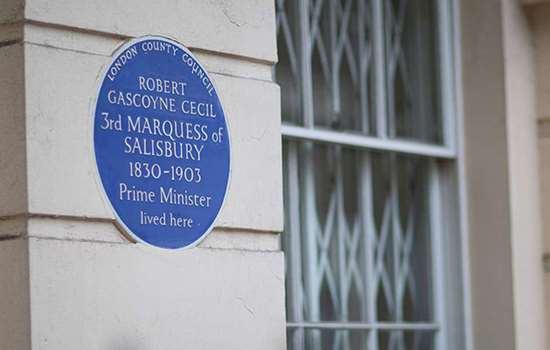

Plaque erected in 1998 by English Heritage at 2 Princelet Street, Spitalfields, London, E1 6QH, London Borough of Tower Hamlets

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Textile Designer

Category

Applied Arts

Inscription

ANNA MARIA GARTHWAITE 1690-1763 Designer of Spitalfields Silks lived and worked here

Material

Ceramic

Anna Maria Garthwaite was one of the foremost designers of flowered silks in 18th-century England. She established her trade at 2 Princelet (formerly Princes) Street, Spitalfieds, and lived and worked there from 1730 until her death in 1763.

WORKING LIFE IN SPITALFIELDS

Brought up a rector’s daughter in Lincolnshire, Garthwaite displayed an early interest in botanical drawing and design. It’s unlikely, however, that she had any formal training in the profession in which she became so successful. She came to London in her early 40s, settling at 2 Princes Street with her sister, the widowed Mary Dannye, and their niece Mary Bacon. Here, Garthwaite established herself as a designer of fashionable fabrics, with a flair for natural forms.

Spitalfields at this time was the centre of the silk industry in England. This was partly owing to the arrival in the 1680s of the persecuted Huguenot communities, who brought their expertise in silks with them from France. Garthwaite would have worked closely with these master weavers and traders. At her peak, in the 1730s and 1740s, she was producing 80 designs for brocaded silks a year, and helped to introduce the ‘principles of painting’ into the loom. Her designs have been found not only in the United Kingdom but also in Europe and North America. Given that the silk and fashion industry was dominated by men at this time, Garthwaite’s success as a single woman in her 40s is remarkable.

DESIGNS

Garthwaite kept meticulous records of her designs and her customers, the greater part of which have survived and are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The collection demonstrates the breadth of Garthwaite’s artistic capabilities. She worked within all of the stylistic trends of the period, and was highly skilled at placing her designs against a fashionable formal background. Her compositions with a floral emphasis have been particularly noted for their grace and individuality.

In the early 1750s her output declined sharply – most likely due to changes in fashion – and by 1756 she had varied her range to include a flowered gauze and a carpet pattern.

Garthwaite’s style doesn’t seem to have been influenced by the leading naturalists of the day, meaning that she most likely visited botanical gardens directly in order to familiarise herself with the wide variety of plants she depicted – which included exotic as well as native species.

Little is known about Garthwaite’s life beyond her designs, and it’s unclear when or where she died. Her will, however, was declared on 24 October 1763, at Princes Street, revealing that she died unmarried and left a modest estate of about £600.