Founding Eugenics

The statistician and explorer Francis Galton (1822–1911) was a cousin of Charles Darwin and, in common with other thinkers from this time, began to apply Darwin’s theories of natural selection to the human race. In its early years, eugenics was dominated by a small and esoteric elite group, which sought ‘scientifically’ to establish ideas about inherited characteristics and abilities that were closely linked to social class and race. Concerns over the size and fitness of the population were not new and the backdrop for the growth of eugenics was a period of enormous social and economic change.

The eugenics movement in Britain was complex and crossed party-political divides but was most evident in the work of two organisations formed in the early 20th century: the Francis Galton Laboratory for National Eugenics and the Eugenics Society.

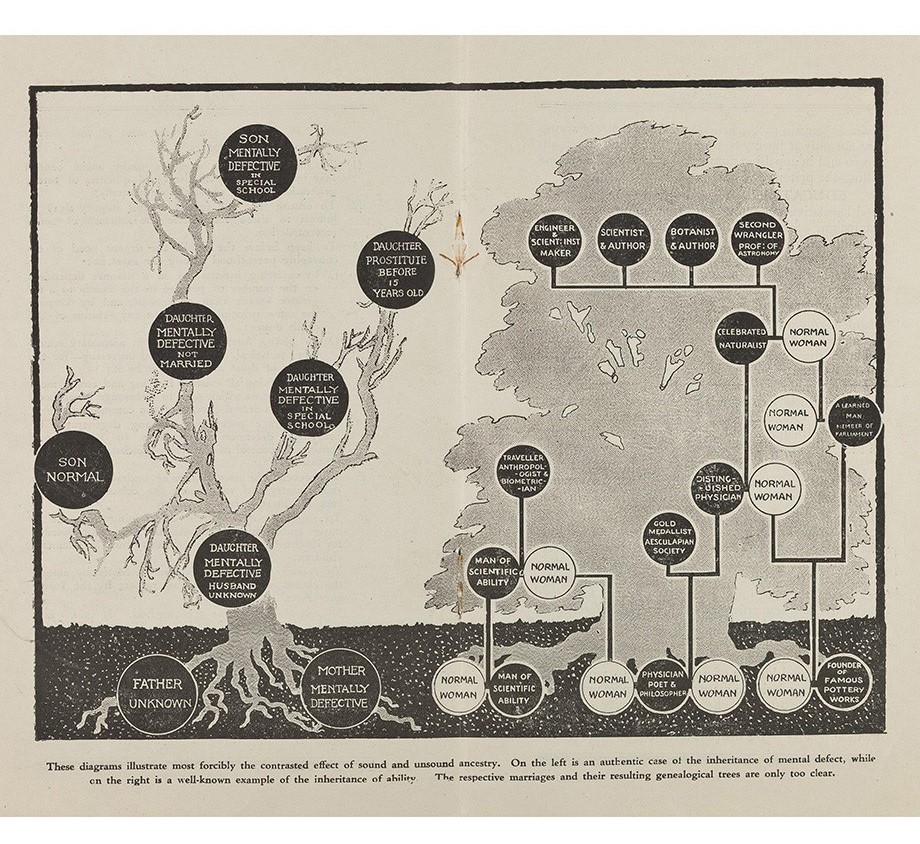

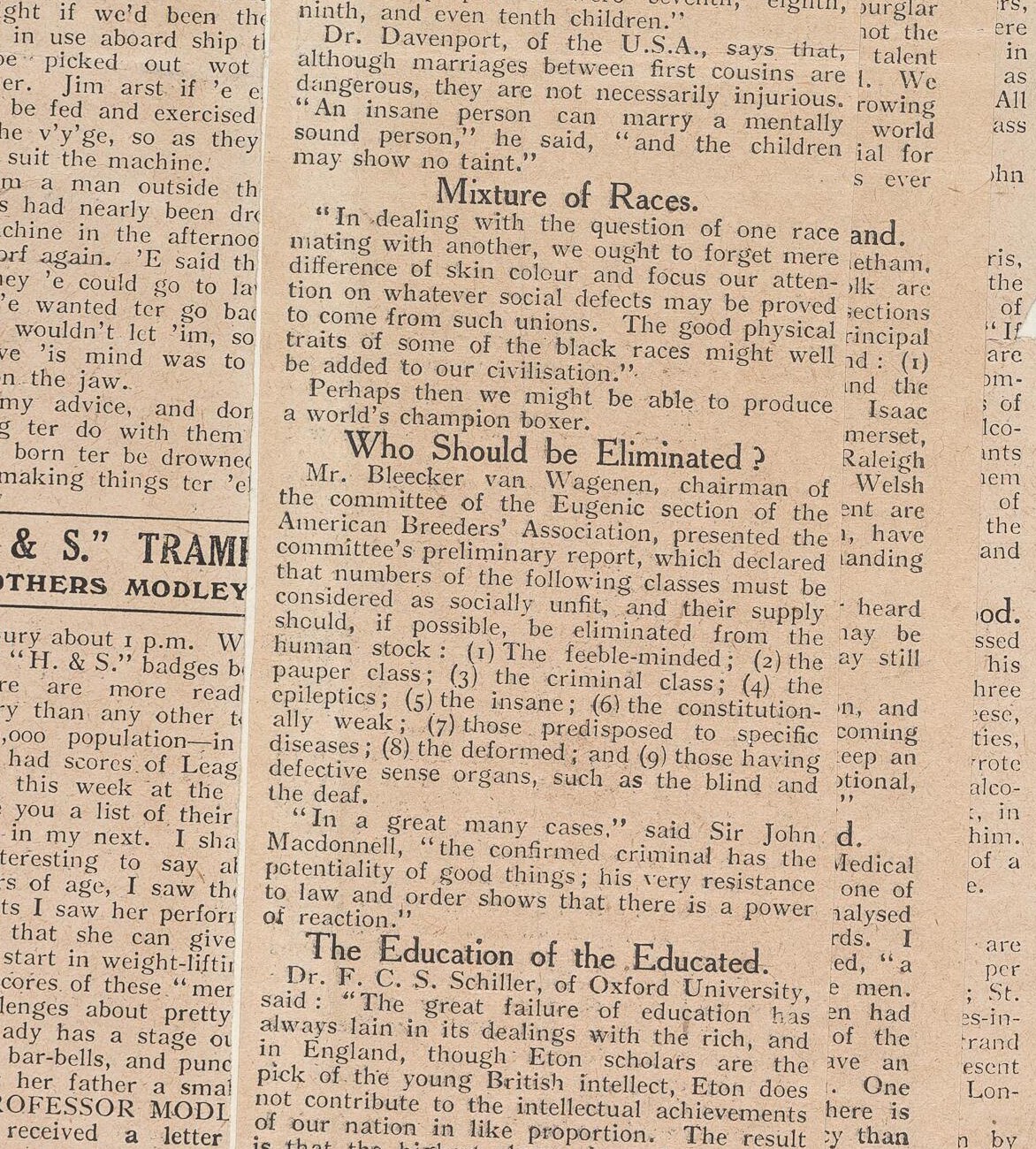

Eugenicists (also known as eugenists) believed they were applying scientific solutions to social problems. Most of Galton’s practical eugenic suggestions were for so-called ‘positive eugenics’ – the improvement of the race by encouraging those couples deemed worthy to have larger families. However, others were more interested in ‘negative eugenics’ – seeking, by various means, to control the reproduction of the ‘unfit’. Such ideas were widely taken up by social scientists, politicians and other public figures as well as those involved in medicine and the sciences.

The Eugenics Laboratory

When in 1907 Galton stepped down as Director of the Eugenics Record Office, which he had helped to found at University College London (UCL), the statistician Karl Pearson accepted his request to take over. Pearson renamed it the Galton Laboratory for National Eugenics and became the first Galton Professor of Eugenics at UCL. Through the journal Biometrika, with which Galton and Pearson were closely involved, the school promoted the study of biometrics (or mathematical genetics). Pearson also set up the Annals of Eugenics in 1925.

Pearson’s eugenic ideas were based on racist ‘science’ that called for the creation ‘of a homogeneous white race, whose fertility shall markedly dominate that of the black’. He held similar views on discouraging reproduction among ‘the unthrifty … the mentally defective’ and ‘the criminal, the tramp and the congenital pauper’, insisting that the right to live did not confer the right to reproduce.

Pearson was succeeded as Galton Professor of Eugenics in 1933 by (Sir) Ronald Aylmer Fisher. Fisher was, in 1911, a founding member of the Cambridge Eugenics Society, whose members included John Maynard Keynes. Like Galton and Pearson, Fisher applied statistical analysis to problems in the evolution of man and was a leading bio-statistician and geneticist. Fisher continued to support eugenics even after the Second World War, by which time it was tainted by association with the genocidal consequences of Nazi race science.

The Eugenics Society

The Eugenics Education Society – renamed the Eugenics Society in 1926 – was founded in London in 1907, due largely to the efforts of social hygienist Sybil Gotto (later Neville-Rolfe). The elderly Francis Galton became its honorary president. The Society sought to promote ‘the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or mentally’, and to ‘intervene whenever a proposed administrative act appears likely to impair the racial qualities of the nation’. Pearson declined to join because it was not a scientific organisation.

For some eugenicists such ideas continued to have a strong racial element, through which to control non-white populations in favour of northern European races. However, the Eugenics Education Society was increasingly more concerned with ‘curing’ a variety of social and physical disorders or traits among the poor. They included alcoholism, habitual criminality, reliance on welfare, prostitution, diseases such as syphilis and tuberculosis; neurological disorders such as epilepsy; mental conditions such as insanity, hysteria and melancholia; and ‘feeble-mindedness’ – a catch-all term for people who were believed to lack mental capacity and moral judgement.

The Society’s records show an overriding concern to prevent those people who were deemed ‘feeble-minded’, ‘degenerate’ or ‘mentally defective’ not just from ‘overbreeding’ but from reproducing at all. Such disparaging terms for people with chromosomal disorders and learning disabilities were then used routinely by scientists, health professionals, educators and social workers, who grouped them with other ‘problem’ people.

Although members usually agreed on the main principles of eugenics, throughout its long history there were differences, especially in its practical application – whether through ‘positive eugenics’ or ‘negative eugenics’.

The Society was never very large, but it was very vocal and its propaganda both reflected and promoted views that were held throughout the upper echelons of society, including government and other institutions. It included prominent scientists and medical professionals alongside the politicians, social reformers, educationalists, leading members of the Church of England, and society figures who were among the most actively involved.

Despite differences between the aims and individual members of the Eugenics Laboratory and the Eugenics Society, the journal The Eugenics Review was published under their joint auspices and became a principal vehicle for promoting eugenic ideas to the public.

The First Eugenics Congress

The Society organised the First International Eugenics Congress in 1912, at the University of London (now Imperial College), in South Kensington, to encourage the international dissemination of eugenicist thinking. Attendance at the congress illustrates how such thinking crossed the arts and sciences and was embraced by both conservative and progressive thinkers.

By this time Galton had been succeeded as president of the Society by Major Leonard Darwin, former Liberal Unionist MP, fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and son of Charles Darwin. The vice presidents included literary hostess and patron of the arts Lady Ottoline Morrell and the writer and sexologist Henry Havelock Ellis.

The British vice presidents of the congress included Liberal politicians Lord Avebury, Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary Reginald McKenna, the chemist Sir William Ramsay, and the presidents of the Royal Society, the Royal College of Surgeons and other leading medical and legal institutions. The welcome addresses were given by the Lord Mayor of London and the former Conservative Prime Minister Arthur Balfour. The American Ambassador, the Duchess of Marlborough and founding Eugenics Education Society member Lady Emily Lutyens hosted congress parties at their London residences.

Some of those who attended the congress in 1912 do not appear to have participated in the Society after that date. And not all participants accepted the Society line without question and some argued against it. In his paper on ‘The Sterilization of the Unfit’, the scientist and anarchist Prince Peter Kropotkin asked who it was proposed to sterilise as unfit – ‘the workers or the idlers, the rich or the poor, the poor women who suckled their children, or the women of the upper classes who refused maternity?’

Critics and Controversy

Some of those who were sympathetic to eugenic ideas, including members of the Fabian Society, were critical of the strict focus upon heredity. They called for greater attention to be paid to environmental factors in the formation of ‘social problem groups’. Fabian social scientists and political reformers Beatrice and Sidney Webb, writer George Bernard Shaw, and economist and politician William Beveridge who sat on the Eugenics Society Consultative Council until the late 1950s, were among the Fabian eugenicists at the London School of Economics.

In general, although there were critics of many features of the eugenics movement, they sought the ‘reformulation, not the defeat, of eugenic ideology’. As Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald put it baldly in 1909, ‘Natural selection by death has been set aside, but the State can set sexual selection in operation again by an education in good taste’. Through environmental reform and the elimination of poverty, MacDonald believed, a race of ‘healthy and comely men and women’ would be encouraged without the need for negative methods such as the segregation of the unfit.

The Mental Deficiency Act

Such opposition became more sharply focused on the introduction of the Mental Deficiency Bill in 1912 – legislation designed to prevent ‘the feeble-minded’ from becoming parents. Critics included Roman Catholics such as the writer GK Chesterton and the poet Hilaire Belloc. In Parliament, the bill was vigorously opposed by the Conservative libertarian Lord Robert Cecil and the Liberal MP Josiah Wedgwood.

Nevertheless, the bill became law in 1913, thereby establishing the means to segregate ‘mental defectives’ in asylums. Due in part to the opposition of Cecil and Wedgwood, it rejected sterilisation. Wedgwood, with some prescience, warned in a letter to The Times that it was ‘impossible for any of us to be certain as to the ultimate result of our actions, or Acts of Parliament’.

Some eugenic ideas were now mainstream, prevalent among leading thinkers, scientists and politicians. But some proponents recanted, were conflicted or held more complex views. The writer HG Wells had supported the Feeble-Minded Control Bill in 1912 – a private members’ bill which preceded the government’s Mental Deficiency Bill. But in 1913 Wells declared ‘not only do I not support eugenists and the Eugenic Society [sic], but … I have written an entirely destructive criticism of their proposals’.

Havelock Ellis did not like Galton’s comparison of animal breeding with human eugenics and later expressed his opposition to compulsory sterilisation of the mentally deficient in letters to the Eugenics Society’s general secretary. Although many feminists supported eugenic ideas, in 1913 Rebecca West condemned ‘the animal life that the Eugenics Society orders women to lead’ in order to focus on home and children.

Between the Wars

In the 1920s the Society changed its position on birth control. The move to promoting contraception for married couples brought it into closer collaboration with women’s groups and others engaged in social welfare. Kindred organisations included the Society for Constructive Birth Control and Racial Progress, the founding president of which in 1921 was Marie Stopes.

Members of the Eugenics Society now included the biologist and zoologist (Sir) Julian Huxley, who was vigorous as vice president in the 1930s and as president in 1959–62, statistician RA Fisher (who later distanced himself on the grounds that the Society was not scientific enough), biologist Sir Peter Medawar, botanist Dame Helen Gwynne-Vaughan, politician Neville Chamberlain, and economist Harold Laski. Social scientist Richard Titmuss and writer WB Yeats joined in the 1930s. Others, who expressed eugenic views but were not members, included Flinders Petrie, Bertrand Russell and Virginia Woolf.

Huxley’s former student CP Blacker, a Maudsley Hospital psychiatrist who joined the Ministry of Health in 1942, was a more liberal, reformist secretary of the Eugenics Society in 1931–52. Under Blacker there was greater attention paid to the role of contraception in reducing fertility, and to population policies.

The economist John Maynard Keynes had opposed the study of inheritance through biometrics, as proposed by Galton and Pearson, in favour of an approach based on probability – shaped by Mendelian theory. He was elected vice president of the Eugenics Society in 1937, believing that eugenics could solve Britain’s problems, which in his view were ‘rooted in the hereditary weaknesses of its leadership’.

Sterilisation

The Sterilisation Bill of 1931 was introduced by Major AG Church, Labour MP for Wandsworth and organising secretary of the Eugenics Society. It aimed to legalise the voluntary sterilisation of ‘mental defectives’. The bill was reproduced in a pamphlet entitled ‘Better Unborn’, which showed the ‘consequences of encouraging fertility of dysgenic stocks’ (people with supposedly undesirable genetic characteristics), with a view to garnering Parliamentary and wider support. It was rejected by 167 votes to 89, the main opponents once again being Roman Catholics and Labour MPs, though most abstained. Among those who did vote for the bill were Eleanor Rathbone and Ellen Wilkinson.

Yet a Parliamentary report (known as the Brock report) of the departmental committee on sterilisation of 1933 was unanimous in its conclusion that ‘allowing and even encouraging mentally defective and mentally disordered patients’ to be sterilised was justified. Only 3 out of the 60 witnesses who gave evidence – comprising psychiatrists, biologists, medical professionals, local authority representatives and social workers – were opposed to its recommendations on principle. The committee considered sterilisation to be a ‘right’ of the mentally ‘defective’ and advocated extending it to those with physical disabilities.

Although it did not derail committed eugenicists from their belief in ‘voluntary’ sterilisation, the rise to power of the Nazis in 1933 and the passing of compulsory sterilisation legislation in Germany may have helped prevent such views from gaining traction in Britain. Attempts in 1934 and 1937 to implement the report of the Brock committee on sterilisation came to nothing, and widespread institutional sterilisation of people with disabilities was not carried out in Britain. Meanwhile the scientific credibility of eugenics was itself under increasing scrutiny.

After the Second World War

In 1945 the Eugenics Society stressed the ‘gulf that separates eugenics from the Nazi doctrines of ‘‘race hygiene’’ and racial superiority’. The aim was now to separate itself from ‘perversions’ of eugenics and redirect attention to Galton’s standpoint – which was not exactly unproblematic. In the same year it repeated its commitment to the Brock committee’s recommendations on voluntary sterilisation, and in this it was increasingly out of step with mainstream thinking.

In the 1950s the Society suggested the implementation of checks on West Indian immigration. It published Colin Bertram’s Broadsheet on West Indian Immigration of 1958 – the recommendations of which included racist ‘considerations’ of quotas for West Indians and testing for the ‘quality’ of attributes of all immigrants. However, the Society also reprinted scientific, anthropological and cultural criticisms of Bertram’s research.

Legacy

The eugenics movement in Britain peddled ideas that today seem offensive and downright dangerous, and had some prominent adherents. However, it never gained truly widespread appeal, and environmental and social reforms were increasingly seen as a more effective – and humane – remedy for social problems. Eugenics was also unsuccessful in its aim of stemming the fall in birth rate among those groups it deemed ‘fitter’, as women sought to control their own fertility by the use of contraception across many social groups.

The Eugenics Society was renamed the Galton Institute in 1989. Since then the organisation has sought to address questions raised by the scientific exploration of human heredity and to promote education and public engagement, not only with the current science but also with its origins and history. In 2020 UCL announced the re-designation of those parts of their premises that had been named in honour of Galton, Pearson and Fisher.

Header image: A Eugenics Society exhibition stall from the 1930s. The Society attended exhibitions such as the Ideal Home Exhibition, the Health and Housing Exhibition and the Health and Beauty Competition. © Wellcome Collection. Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

FURTHER READING

Archival records

The Eugenics Society Archive, Wellcome Collection (accessed 11 May 2021)

‘First International Eugenics Congress, London, July 24th to July 30th 1912, University of London, South Kensington: Programme and Timetable’, Wellcome Collection (accessed 11 May 2021)

JR MacDonald, Socialism and Government (London, 1909)

‘Report of the Departmental Committee on Sterilisation, 1933’, Wellcome Collection (accessed 11 May 2021)

Modern Histories

I Bhullar and D Challis, ‘Eugenics and Social Biology at LSE Library: An Introduction’, Decolonising LSE Collective, 2 November 2019 (accessed 11 May 2021)

D Challis, The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie (London, 2013)

DJ Childs, Modernism and Eugenics: Woolf, Eliot, Yeats, and the Culture of Degeneration (Cambridge, 2001)

RS Cowan, ‘Galton, Sir Francis (1822–1911)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2005) (subscription required; acccessed 11 May 2021)

LA Farrall, Origins and Growth of the English Eugenics Movement, 1865–1925 (London, 1969) (accessed 11 May 2021)

M Gilbert, ‘Leading Churchill Myths: “Churchill’s campaign against the ‘feeble-minded’ was deliberately omitted by his biographers”’, International Churchill Society, 2011 (accessed 11 May 2021)

BW Hart, ‘Watching the “eugenic experiment” unfold: the mixed views of British eugenicists toward Nazi Germany in the early 1930s’, Journal of the History of Biology, 45:1 (2012), 33–63

D Paul, ‘Eugenics and the Left’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 45:4 (1984), 567–90

D Redvaldsen, ‘Eugenics, socialists and the labour movement in Britain, 1865–1940’, Historical Research, 90:250 (2017) (accessed 11 May 2021)

D Singerman, ‘Keynesian eugenics and the goodness of the world’, Journal of British Studies, 55:3 (2016), 538–65

HG Spencer, ‘Fisher, Sir Ronald Aylmer (1890–1962)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) (subscription required; accessed 11 May 2021)

RA Solway, Demography and Degeneration: Eugenics and the Declining Birthrate in Twentieth-Century Britain (Chapel Hill and London, 2014)

P Weindling, ‘Julian Huxley and the continuity of eugenics in twentieth-century Britain’, Journal of Modern European History, 10:4 (2012), 480–99 (accessed 11 May 2021)

J Woiak, ‘Pearson, Karl (1857–1936)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) (subscription required; accessed 11 May 2021)

‘Bricks + Mortals: a history of eugenics told through buildings’ (podcast), UCL

‘Ronald Aylmer Fisher (1890–1962)’, UCL (accessed 11 May 2021)