The Scientific method and smallpox

The value of experimental science to the understanding of disease is fundamental. Without some understanding of the cause and nature of an illness, devising treatments and cures is reduced to guesswork.

We owe much in this regard to a gruff and rather charmless 18th-century surgeon named John Hunter. His nigh-on obsessive collecting of biological specimens helped to increase understanding of how the human body works, and his dedication to empirical method – making deductions from observations and experiments – was a tremendous influence on those who followed.

One of Hunter’s pupils was Edward Jenner, the Gloucestershire physician who developed a vaccine for smallpox, a viral disease causing a high fever and a severe rash. Smallpox was a major cause of blindness and death, and recovered patients often suffered scarring.

Sydney Monckton Copeman built on Jenner’s work, coming up with a way to ensure that the smallpox vaccine remained sterile, hence removing the risk of bacterial infection. This paved the way for a worldwide vaccination programme, and the elimination of this once-feared contagion.

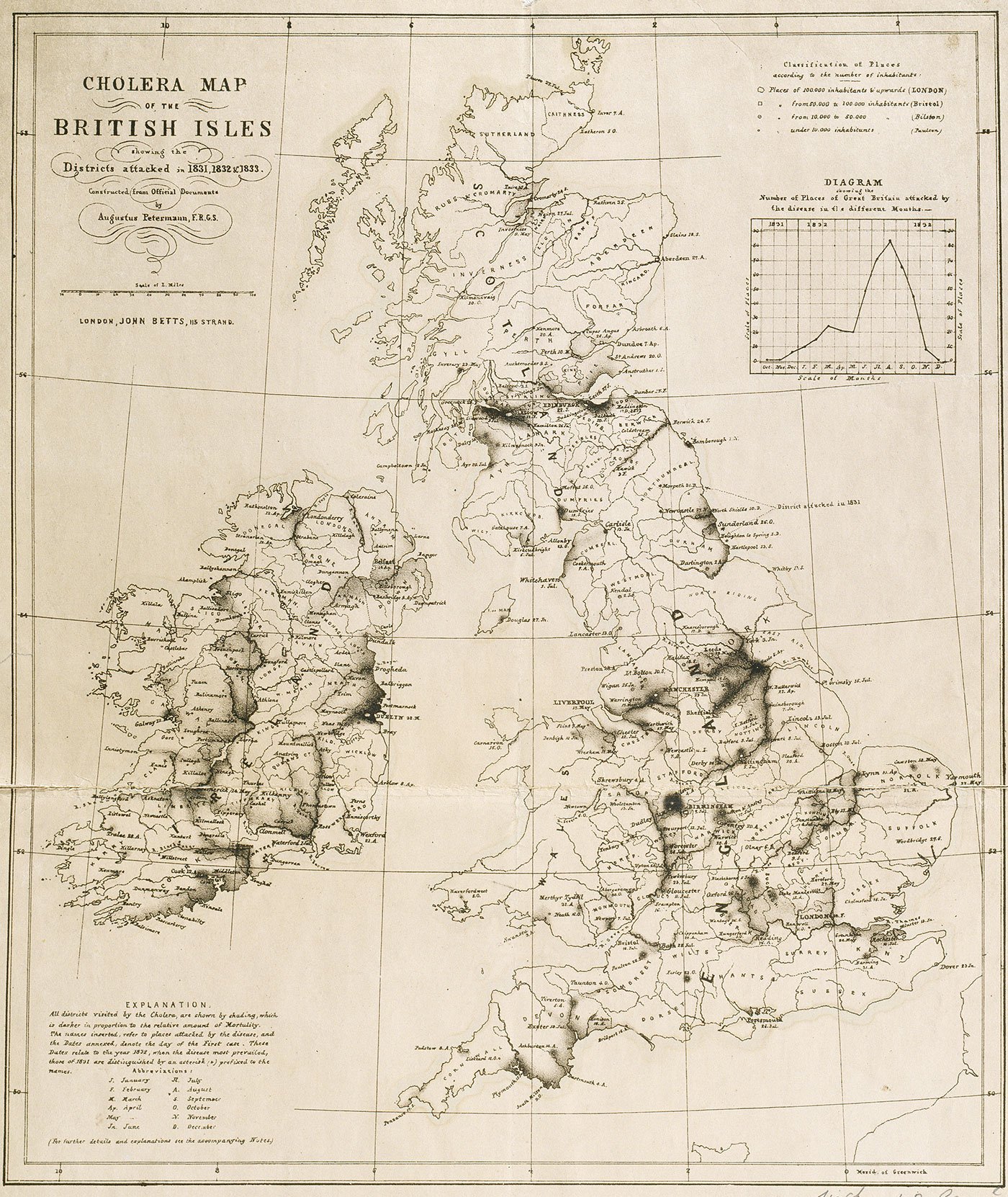

Cholera

There were six cholera pandemics throughout the 19th century. This disease, which came originally from India, first arrived in England in 1831. Its presence was initially denied by those who felt their business interests threatened.

Cholera, which can cause death by dehydration within hours, is caused by the contamination of drinking water with faeces. Unfortunately, this was not fully established and accepted until the later 19th century, by which time it had killed close to 150,000 people in the British Isles alone.

Diseases of unknown origin can breed a fear of sufferers. One brave doctor with no such qualms was William Marsden, who – unlike many others – admitted poor cholera patients to his foundation in Greville Street, Holborn. Here, at the hospital that became the Royal Free, Marsden successfully treated cholera victims with a saline drip.

In a later epidemic of 1865, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was another to step forward. In these conditions, she found that the prejudice that existed against her as a female doctor largely evaporated, and she was given the chance to put her skills to use.

Health and sanitation

The first to identify cholera’s origins in water sources was John Snow in 1854. He is commemorated in Soho by an unofficial plaque not far from the contaminated pump which he pinpointed as a source – and prudently removed the handle to prevent its use.

At around the same time this link was explored further by Sir John Simon, who was successively chief medical officer to the City of London and to national Board of Health. Simon became convinced that ‘the frightful phenomenon of a periodic pestilence belongs only to defective sanitary arrangements’.

His predecessor at the Board of Health, the combative Sir Edwin Chadwick, was behind the first Public Health Act, of 1848, and showed an early awareness of the link between poverty and disease. Both Simon and Chadwick took Hunter’s cue in seeing scientific research as vital, along with the collection of accurate statistics.

Vital too were engineering skills to provide the means for sanitation and a clean water supply. Joseph Bazalgette is well known as the designer of London’s remarkable system of sewers.

A less recognised name is William Lindley, a civil engineer whose advocacy of the sand filtration system for water supplies was vital to the banishment of cholera from the western hemisphere. In parts of the world without clean water, the disease remains a potent threat.

Public health and the eradication of rabies

Chadwick and Simon both clashed with officialdom and governments of their day, in their attempts to push for stronger action on public health. Chadwick found himself sidelined while Simon, according to an obituary, resented ‘the constantly recurring pinpricks of official interference'.

From a later generation, another strong character was Sir Victor Horsley, a pioneering neurosurgeon whose other gift to posterity was the eradication of rabies from the British Isles.

In the 1890s, Horsley successfully pressed for the compulsory muzzling of dogs, against much opposition from animal lovers. But muzzling worked – an example of where the containment of a contagion depended upon restricting certain freedoms.

Hospital care

For any illness, a patient’s recovery can depend greatly on the quality of hospital facilities and on dedicated nursing care. Ethel Gordon Fenwick was a key figure in raising the professional standing of nurses in the early 1900s, with her campaign for state registration.

Earlier, the Scottish-Jamaican nurse Mary Seacole came to prominence for her treatment of the wounded in the Crimean War, but already had experience of nursing victims of cholera outbreaks.

Good hospital hygiene is strongly associated with another famous figure from the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale. Her insistence on clean wards and fresh air was based on the later discredited ‘miasmic’ theory that disease was spread by bad air. However, since dirt harbours germs, her course was correct – but for the wrong reason.

The NHS

Florence Nightingale was a leading supporter of Dr Joseph Rogers, whose disgust at the state of workhouse hospital provision for the poor led to the establishment of London’s first public hospitals from the 1860s onwards.

Later, Rogers’s hospital foundations were incorporated into the National Health Service. This was conceived in outline by Sir William Beveridge as part of the social provision envisaged in his 1944 report, and delivered – in comprehensive form, free at the point of use – by Nye Bevan in 1948.

Many diseases and illnesses that once ravaged the globe have now been conquered, or are not the threat they once were. This is thanks to the work of pioneering doctors, health care workers, public health professionals and visionary decision-makers who have found effective and practical ways to mitigate and prevent their spread. It is talents such as these that have helped to bring Covid-19 under control.

Explore More

-

London Poverty: Chaplin and Dickens

Discover how Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp and Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist were inspired by childhood experiences of poverty.

-

Celebrating London’s Black History

From sporting heroes to statesmen, discover some of the pioneering black figures whose achievements are celebrated with London’s blue plaques.

-

Pioneering women in London

Take a look at some of the figures in London’s history commemorated by blue plaques who fought to open up new opportunities for women.